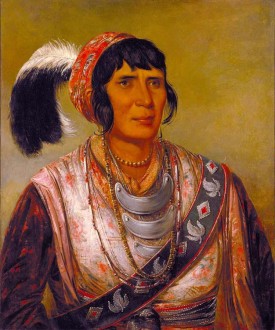

The Seminole Indian Coacoochee blazed an extraordinary trail through life, in a dizzying myriad of guises: ferocious warrior, vainglorious showboat, impudent rogue and mercurial firebrand “given to dramatic acts and alcoholic episodes,” as one scholar puts it. A spellbinding orator, visionary diplomat, gifted mystic and charismatic leader who, before the Civil War, engineered an Underground Railroad leading to a multiethnic utopian colony in Mexico. Memorialized in the signature cry of the Mardi Gas Indian Spy Boy — Coochee Malay! — he also may be the key to unsolved mysteries of a “masking” tradition that has become emblazoned on the cultural consciousness of New Orleans and beyond.

Big Chief Wild Cat:

Coacoochee and the dawn of Mardi Gras Indians

By Graham Button

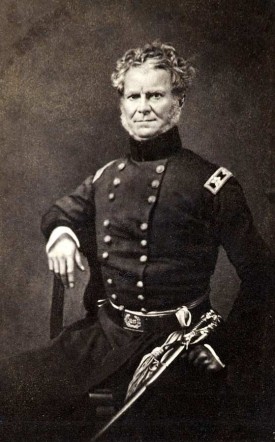

Engraving of Coacoochee sketch attributed to N. Orr

The Mardi Gras Indian expression Coochee Malay memorializes his legacy as an indomitable hero who not only fiercely resisted removal but welcomed runaway slaves, championed the cause of black tribesmen and made possible an Underground Railroad leading to the Black Seminole colony in Mexico.

Image courtesy of the Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma)

In a scene from the documentary film The Black Indians of New Orleans, the rooftops of the city’s 10th Ward are silhouetted by the orange break of dawn, as dogs bark and screen doors open and close. Spy Boy Nat, of the White Eagles Mardi Gras Indian tribe, emerges from a humble doorway as if from chrysalis — in full yellow bloom, radiating ebullience.

“I’m the Spy BOY,” he hollers. “I’m the spy boy that morning. Spy Boy Coochee Malay, all in stones. I’m the Spy BOY!”

He turns to the camera and, flashing a triumphant smile, sashays with his arms extended to reveal the full magnificence of his regalia — a multi-layered array of plumage, beadwork and faceted crystals (“stones,” in the parlance of Mardi Gras Indians). “Cuffs” hang from his arms like gaudily trimmed draperies, and his encoded outbursts — an odd-sounding, creolized vernacular handed down through generations of oral tradition — hint at the alluring mysteries of his culture.

“Spy Boy hauling apple. Ah-chee mali baum-baum…,” he proclaims. “Let the sun shine! Let the sun shine that morning!”

When Black Indians was released in 1976, its subjects still constituted a secret society. Parading on neighborhood back streets, they showed little interest in sharing their traditions with the outside world, and attracted only a handful of admirers from beyond the predominantly black, working-class communities that had sustained the culture as a living, and continually evolving, art form since the 1800s. Doors slammed shut on perceived “hustlers” seeking interviews and access for documentary purposes. Practically any “outsider” angling for an “insider” perspective was, by default, suspect.

By the late 1970s, even after gaining some notoriety through commercial recordings of their music and appearances at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, Mardi Gras Indians were, at best, a curiosity in the eyes of the local tourism and media establishment. Those who “masked” Indian certainly didn’t seek validation from such quarters, and images of their pageantry and sartorial brilliance simply didn’t figure into marketing campaigns celebrating the city’s heritage.

From back streets to bright lights

But what was once a strictly underground phenomenon has, alas, gone mainstream. As Mardi Gras Indians have evolved from an unruly fringe element harassed by police into celebrated icons, their music and folkways have become emblazoned on the cultural consciousness of New Orleans and beyond. Their costumes or “suits” are now featured in prestigious art exhibitions, while the HBO series Treme, in which Mardi Gras Indians figured prominently, brought the culture to a mass audience. The tribes or “gangs” are now seen as emblematic of New Orleans’s unique identity — a major draw for “cultural heritage” tourists and a fertile subject for a growing body of literature. They attract swarms of photographers, receive prominent media coverage and have been featured in a parade of documentary productions — notably, Always for Pleasure, Cutting Loose, All on a Mardi Gras Day, Tootie’s Last Suit and Bury the Hatchet.

Also joining in salute: The National Endowment for the Arts, which in 1987 awarded the late Allison “Tootie” Montana of the Yellow Pocahontas a National Heritage Fellowship. The late Theodore Emile “Bo” Dollis of the Wild Magnolias received the award, considered the nation’s top honor in folk and traditional arts, in 2011.

Victor Harris, chief of the Mandingo Warriors, a k a Fi Yi Yi, on Carnival Day 2013

What was once a strictly underground tradition, more or less ignored by the New Orleans tourism establishment, is now a recognized as a vital living art form — attracting the interest of museum curators, TV producers and documentary filmmakers.

Photo ©MardiGrasTraditions.com

Some Indians, meanwhile, have taken to performing for conventioneers and busking for tips in the French Quarter. They’ve even appeared in television advertisements for a regional supermarket chain and an enterprising local lawyer.

Although these developments have prompted concern about the demystification and commercialization of the culture, there is consolation in continuity. For there’s no denying that the Indians still have the “fiya,” earning props not only through artistic skill and performance ability — singing, dancing and mastery of the protocols and dramaturgy of “playing Indian” — but also by serving as mentors and community role models. And the competitive aspects of their art and revelry — the never-ending quest to design and show-off the “prettiest” suit — ensure plenty of dynamism. Sartorial innovation commands respect, and there’s no end to the creativity that goes into making a suit that illuminates a theme or tells a compelling “story.” (Interpretations of historical personages and events, as well as commentary on contemporary culture and current affairs, are mainstays of the craft.)

So, regardless of their newfound celebrity, Mardi Gras Indians remain a thoroughly arresting spectacle. And despite all of the concerted efforts to explain their origins, decode their utterances and song lyrics, and dissect the “meaning” of their customs, there are still unsolved mysteries to ponder. Which brings us back to Coochee Malay (pronounced Mah-lay) and Spy Boy Nat, a k a The Coochee Malay Man, in the groundbreaking film The Black Indians of New Orleans.

A coded expression referencing a conduit for escape

Coochee Malay is the signature cry of the Mardi Gras Indian Spy Boy, whose tribal function is to serve as the eyes of the Big Chief. Usually stationed several blocks ahead of the chief, his job is to scout out or “spy” other Mardi Gras Indian tribes in the vicinity, then signal the Flag Boy or other intermediary, who in turn relays the information to the Big Chief. The chief then decides whether to meet the espied tribe or proceed in another direction, to search for other Indians. Since much of the fun of being a Mardi Gras Indian comes from flaunting one’s regalia and engaging with other tribes, in ritualized confrontations known as “challenges,” a savvy Spy Boy must possess a sort of sixth sense when it comes to knowing where to locate other Indians. An Indian assuming this position or role is, in the argot of the street, said to be “runnin’ spy.”

Black Indians doesn’t attempt to decipher Coochee Malay or explain why the phrase is associated with the Spy Boy. But the auteur behind the film, Maurice Martinez, enlightened an audience at the 2010 Jazz & Heritage Festival, while moderating a discussion with Big Chief Romeo Bougere and members of his Ninth Ward Hunters tribe of Mardi Gras Indians.

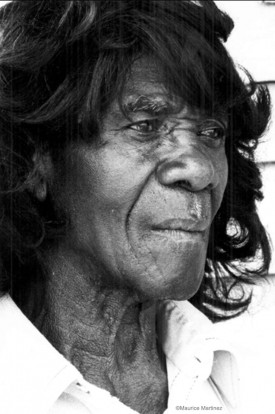

Nathan “Spy Boy Nat” Williams of the White Eagles Mardi Gras Indians

The “Coochee Malay Man” played a starring role in the groundbreaking 1976 film The Black Indians of New Orleans, which offered a revealing glimpse into what was then a secret society.

Photo ©Maurice Martinez

Coochee Malay is commonly understood to mean “Here I am!” It’s a shout that Spy Boys — and sometimes their tribal cohorts — use to announce one’s presence and command attention, as in “Spy Boy, Coochee Malay!” Or a Spy Boy might announce, “Big Chief, Coochee Malay!” as in “Here’s the chief!” or “Make way for the chief!”

Prefacing his interpretation, Martinez (pronounced Mar-tin-ez) offered a provocative assertion: that the story of Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad, as taught in classrooms across America, is “a distraction.” That, in fact, there were other pathways to freedom that were truly “underground,” in the sense that they were purposely never intended to become part of the mainstream narrative about slavery. A key player in the “real” Underground Railroad, Martinez informed his Jazz Fest audience: the Seminole Indian chief Coacoochee, also known as Wild Cat.

A Creole from the New Orleans’s Seventh Ward who has delved deeply into the peculiarities of Creole and Mardi Gras Indian locutions, Martinez noted that “we” — meaning Creoles and New Orleanians generally — have a tendency to shorten words by dropping syllables. Hence, “Coacoochee” (pronounced Co-AH-coochee or Go-AH-coochee) becomes “Coochee.”

“So when Coochee came along,” Martinez related, “he say, ‘Follow me to freedom; get out of this wretched existence you in, in this racist South.’ And of course, in Creole you don’t say Je vais — ‘I go’ — you say, ‘Me go.’ So it’s Moi aller, not Je vais. When you say it fast enough, it’s Malay.” Coochee Malay became, in other words, a coded expression of those who saw Coacoochee as a conduit for escape. Loose translation: “Coochee, here I am! Me go with you to freedom.”

To Indian Territory via New Orleans

There is little doubt that slaves and free people of color in 19th century New Orleans would have found much to admire in Coacoochee. By the time he first set foot in the city, in 1841, he’d already acquired a formidable reputation as a warrior and resistance leader in the Second Seminole War in Florida, battling U.S. efforts to remove his people west to Indian Territory. Black Seminoles — comprised mostly of runaway slaves and their descendants — figured prominently in the first phase of that war, fighting in alliance with native Seminoles.

Maruice Martinez interviewing Big Chief Markeith Tero of the Trouble Nation Mardi Gras Indians at the 2013 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival

A keen interpreter of Creole and backstreet New Orleans vernacular, he decoded the meaning of “Coochee Malay” and revealed the “sacred” connection between Coacoochee and the Mardi Gras Indians.

Photo ©MardiGrasTraditions.com

They became known as Black Seminoles or Seminole Negroes not so much because they were of mixed blood — intermarriage with members of the Seminole tribe was, in fact, infrequent — but rather because they were of African descent and had become closely associated with the Seminoles in Florida — a haven for blacks fleeing racism and bondage in Georgia and Carolina.

Between 1836 and 1842, according to The Encyclopedia of American Indian Removal (edited by Daniel F. Littlefield, Jr. and James W. Parins), an estimated 4,200 Seminoles and Black Seminoles capitulated to the U.S. government’s removal demands. New Orleans served as a way station on their journey from Florida to their new home in the West. Most of the Black Seminoles agreed to surrender on the promise of receiving protection and freedom in Indian Territory, but they would up having their hopes dashed as the slave trade encroached on their existence.

Coacoochee shared their sense of indignation. The land and climate in Indian Territory were a poor substitute for what the Seminoles had left behind in Florida, and U.S. government overseers demanded that Coacoochee and his people not only live in close proximity to their traditional enemies, the Muscogees (Creeks), but also submit to their laws, which included harsh slave codes.

“Gopher John” (a k a John Horse) illustration by N. Orr

The trajectory of his colorful life, beginning in Florida and ending in Mexico — with stops along the way in Indian Territory, Washington, D.C. and New Orleans — intersected with Coacoochee’s in ways that were destined to shape history and transform him into a cultural icon.

Image courtesy of the Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma

Making a pact with his old friend and comrade from Florida, John Cowaya, a k a John Horse, leader of the Black Seminoles, the restless chief decided to bust a move. In 1849, Coacoochee led a contingent of Seminoles and black tribesmen on an epic journey to Mexico, where slavery had been outlawed and the government was welcoming immigrants willing to serve in a military capacity. Once established, the Black Seminole colony south of the border became a magnet for runaways from slave states, just as the Seminole settlements in Florida had become a refuge for fleeing slaves decades earlier. Eventually, most of the Black Seminoles in Mexico relocated to Texas. There they gained fame serving as scouts for the U.S. Army, helping to secure the borderlands against raids from hostile tribes.

Back in New Orleans, the retained memory of Coacoochee and the Black Seminoles who served as scouts — four of whom won the coveted Medal of Honor — came together in the persona of the Mardi Gras Indian scout or Spy Boy. Coochee Malay became the Spy Boy’s shout-out to Coacoochee and his legacy as an indomitable hero who championed the cause of black tribesmen and made possible the Underground Railroad leading to the Black Seminole colony in Mexico.

Overlooked history concealing a hidden mystery

In literature and documentation touching on the origins of Mardi Gras Indians, one encounters many generalities about how Native Americans provided refuge to runaway slaves, intermarried with people of color and shared with them the common experience of subjugation. Slaves and their descendants identified with tribes and chiefs that fiercely resisted colonial domination. Famous Indian warriors and their exploits are, in fact, depicted on the beadwork “patches” that adorn some Mardi Gras Indian suits today. And the familiar Mardi Gras Indian lyric “Won’t bow down/on that dirty ground” speaks to the shared struggle of Indians and blacks to maintain dignity in the face of oppression.

The legendary “Chief of Chiefs,” Allison “Tootie” Montana

An exceptionally dedicated practitioner whose suits continually raised the bar in terms of design and craftsmanship, the late chief of the Yellow Pocahontas also is revered for his decisive influence in steering competition between Mardi Gras Indians tribes away from physical confrontation and toward aesthetics, as well as for speaking out about the contentious relations between Mardi Gras Indians and the New Orleans police force.

Photo ©Maurice Martinez

African and Native American peoples also had a spiritual kinship based on the conviction that, as bell hooks observes in her essay “Black Indians,” “the dead stay among us so that we will not forget.” Ritual and performance in both cultures reflected a belief system in which the living worshiped and celebrated among the spirits of their ancestors. In this sense, Mardi Gras Indians see themselves as caretakers of memory, and their ritual can be interpreted not as mimicry but as a reenactment of historical consciousness.

But for all the pontificating about these common affinities, few if any concrete examples have surfaced that explicitly connect the origins of the Mardi Gas Indians to specific instances of affiliation between runaways and Amerindians. The derivation of Coochee Malay, and the extraordinary story of Coacoochee and the Black Seminoles, can thus been seen as a key missing link to understanding not only the genesis of the Spy Boy but the entire Mardi Gras Indian tradition.

As far as written history, the Seminole connection to Mardi Gras Indians has been almost completely overlooked. Journalists and historians often cite Becate Batiste as the first chief to preside over a tribe of Mardi Gras Indians, the Creole Wild West, in the 1880s. The original source for these accounts, according to Martinez, was Becate’s great nephew, the legendary “Chief of Chiefs,” Tootie Montana, who died unforgettably in 2005 — collapsing at a podium while passionately addressing the New Orleans City Council about the contentious relations between Mardi Gras Indians and police.

Tootie’s knowledge of Becate had been passed down to him through oral tradition, and this helps explain why so little documented history about early Mardi Gras Indians exists. Interviewing participants for documentary purposes was unheard of until New Orleans poet and historian Marcus Christian gathered material during the 1930s for a study of African Americans in Louisiana. The Works Progress Administration’s Louisiana Writers’ Project in the 1940s also produced noteworthy glimpses of the culture, but hardly opened the floodgates. Indeed, when Martinez interviewed Tootie Montana and Gerald “Jake” Millon, chief of the White Eagles, in 1975 for his documentary film, it was, among the cognoscenti, considered a coup.

The Buffalo Bill theory

The mystery surrounding people of color in New Orleans taking to the streets as Indians has prompted much speculation. Might the first Mardi Gras Indians have been inspired by the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show, which spent several months in New Orleans while the city hosted the 1884-1885 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition? The show, as described by historian Daniel H. Usner Jr., featured real Plains Indians attacking a stagecoach, high-stepping to a war dance and hunting a buffalo. If it was Becate who coined the name the Creole Wild West, was he tipping his feathered headdress to Buffalo Bill Cody’s “Wild West” extravaganza?

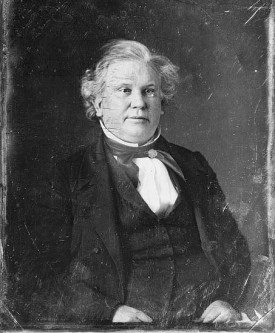

William “Buffalo Bill” Cody

While some observers have maintained that his “Wild West” extravaganza, which wintered in New Orleans in 1884-1885, inspired the Mardi Gras Indian tradition, oral history and the legacy of Coacoochee suggest otherwise.

Photo by Sarony (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

The Buffalo Bill theory of the origin of Mardi Gras Indians — advanced most notably by the late photographer Michael P. Smith — has been the subject of considerable debate. In his book Mardi Gras Indians, Smith points out that the cotton expo included “appearances by American Plains Indians, Mayan Indians and other indigenous peoples, all in native costume.”

Mardi Gras 1885 was “extraordinary,” he writes. “On the streets were large numbers of international visitors connected with the Exposition, several Central American Indian groups, and some fifty to sixty Plains Indians from the Wild West Show, including four chiefs, all of whom were likely on the street in their native dress…. The oral history of present-day Mardi Gras Indian gangs begins at just about that time.”

Martinez, for his part, doesn’t buy the Buffalo Bill theory. No contemporaneous written account has surfaced linking the Creole Wild West, or Mardi Gras Indians generally, to the Buffalo Bill show. More importantly, says Martinez, oral history does not lend support to the theory.

It took years for Martinez to network his way into the Mardi Gras Indian community and gain enough trust to have access to the oral history, which was never intended for the enlightenment of people from outside the culture. His Black Indians documentary enhanced Martinez’s credibility and afforded him opportunities to connect with additional informants, including one old-timer who masked Indian well before Tootie Montana came on the scene. Martinez’s sources also included so-called “Hawks” — elders who didn’t mask but steadfastly preserved institutional knowledge by committing to memory details of suits from years past.

Not one of Martinez’s informers ever mentioned the Buffalo Bill show. At least two of them did, however, acknowledge Coacoochee.

The guarded truth of a sacred connection

After completing his film, Martinez exhibited it on the festival circuit and at old-folks homes in New Orleans. “On one occasion,” he recalled in an email, “an elder by the name of Eddie Richardson came up to me with a big smile, and we talked for hours.” Turned out that Richardson, who was born in 1903, masked Indian beginning around 1915, eventually becoming chief of his own tribe, the One Eleven. Martinez asked him about the meaning of Mardi Gras Indian song lyrics, chants and expressions. “He told me, in a tone of secrecy, that Coochee Malay (the outcry of a Spy Boy) went back to Coacoochee, who took slaves to freedom.”

Danny Lambert, legendary chief of the Wild Squatoolas

One of Martinez’s old-time Indian informants who spoke of Coacoochee with guarded reverence, acknowledging the Seminole chief’s heroic status in Mardi Gras Indian lore.

Photo ©Maurice Martinez

Further verification came from another elderly former chief, Danny Lambert, who presided like a general over an enormous tribe, the Wild Squatoolas, whose number could approach, if not at times exceed, 100. Martinez says that whenever Coacoochee came up in conversations and interviews with his informants, they spoke guardedly, as if “they almost didn’t want to go there…. I felt that it was something sacred, not to be revealed.”

In his email, Martinez confessed to having reservations about possibly breaching a “sacred tradition” by divulging the connection between the legendary Seminole chief, who succumbed to smallpox in Mexico in 1857, and the Mardi Gras Indians. But the educator in Martinez — he is a professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Watson College of Education — got the better of him. Enough time has passed, he writes, and “I feel the world should know why these guarded truths were kept so secret. It was an act of preservation,” necessary for “survival in an oppressive colonial society.”

The Mardi Gras Indian phenomenon can be understood as a reaction to the tribulations of being marginalized in such a society. In New Orleans, a slave-trading mecca, adopting the Indian persona was simultaneously a symbolic expression of ritual freedom and resistance; an act of homage to Indians who gave sanctuary to runaways in colonial times; and a means of channeling and preserving African forms of song and dance.

To see how Coacoochee fits into this picture, however, one must pull on threads that run through the broader fabric of North American colonization. For his story, and the case for the Black Seminoles and he as lodestars for Mardi Gras Indians, is woven into the history and politics of slavery and Indian removal, and extends to the enforcement of color lines governing participation in pre-Lenten festivities (Carnival) and society generally. The overall geographic arc ranges from the southeast through Louisiana to the borderlands of Mexico, bringing to mind the words of Ralph Ellison in Going to the Territory:

“For the slaves had learned through the repetition of group experience that freedom was to be attained through geographical movement, and that freedom required one to risk his life against the unknown. [Geography] has performed the role of fate, but it is important to remember that it is not geography alone which determines that quality of life and culture. These depend on the courage and personal culture of the individuals who make their homes in any given locality.”

By this reckoning, black and Indian cultural connections during the colonial era are key to understanding how Mardi Gras Indians came to exist in New Orleans. For colonialism and its byproduct — slavery — made it inevitable that these two cultures would intersect in ways that would shape history.

Indians and Africans in Bienville’s Louisiana

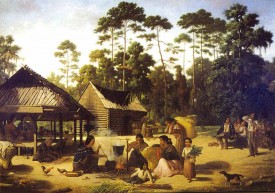

Choctaw Village near the Chefuncte by François Bernard, 1869

As allies of the French, who relied on Indians for survival in the early days of the Louisiana colony, the Choctaw assumed a position economic and political advantage among tribes engaged in regional trade in the Lower Mississippi Valley.

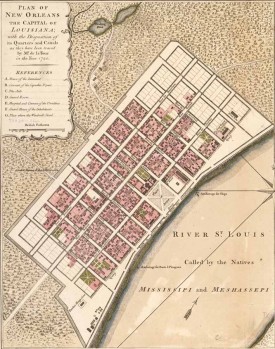

Indians figured more prominently than Africans in the early development of the Louisiana colony. In 1718, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur d’Bienville, a French-Canadian explorer acting on behalf of the French Crown, established New Orleans as a permanent settlement. Bienville chose a site surrounded by a giant crescent bend in the Mississippi, after being led there by Indians via a portage from Lake Pontchartrain.

In the early days of the Louisiana colony under the governorship of Bienville, enslaved Indians far outnumbered enslaved Africans. But the general recalcitrance of Indians, and their familiarity with terrain and local tribes, made it hard to keep them in bondage. Frustrated by Indian runaways, Bienville (for the most part unsuccessfully) championed the idea of sending Indian slaves to the West Indies in exchange for African slaves. The first ships bringing enslaved Africans to Louisiana arrived in 1719.

In his book Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in a Frontier Exchange Economy: The Lower Mississippi Valley before 1783, Usner points out that because “Louisiana remained a deprived and isolated satellite of the French empire,” settlers and soldiers came to depend heavily upon Indian villages “for both subsistence and security.”

“Many colonists,” Usner notes, “owned their survival to Indian villagers who provided food during hard times.”

During the eighteenth century, native peoples were a familiar sight in New Orleans. As Usner observes in another study, American Indians in the Lower Mississippi Valley: Social and Economic Histories, “The capital of colonial Louisiana was home to Indian slaves captured in warfare and host to Indian diplomats from neighboring tribes. Many local villages also produced valuable trade items, especially food, for the New Orleans market and thereby established enduring ties to the colonial town.”

J.C. Buttre portrait of Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur d’Bienville

Under his governorship, as slave labor became increasingly important to Louisiana’s colonial economy, fraternization between Africans and Indians was regarded as a threat requiring suppression.

Usner’s scholarship also highlights the varying dimensions of Indian interaction with people of African descent in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Slaves, free people of color and Indians participated in what he terms a “frontier exchange economy,” which evolved into “a strategy of survival” and a framework for cross-cultural relations. But inter-colonial rivalry between the French and British for influence in the Lower Mississippi Valley, coupled with the rise of the plantation economy, destabilized this network of relationships and led to tougher laws governing interaction among slaves, settlers and Indians. The colonial divide-and-rule agenda, according to Usner, disrupted tribal relations, heightened ethnic tensions and circumvented traditional roles.

Africans, for example, found themselves working for the French as enslaved soldiers in wars against hostile Indians, sometimes earning their freedom by doing so and becoming a permanent part of the Louisiana militia force. With encouragement from colonists, Indians enslaved members of enemy tribes. Some Indians became bounty hunters for escaped African slaves, who sometimes found refuge among sympathetic local tribes.

In a pattern repeated in Florida and along the border between Texas and Mexico, “intercultural collusion” (Usner’s term) between Indians and Africans aroused much trepidation among colonial officials, white settlers and slaveholders. Permitting such collusion to go unchecked was, for Bienville, tantamount to encouraging rebellion.

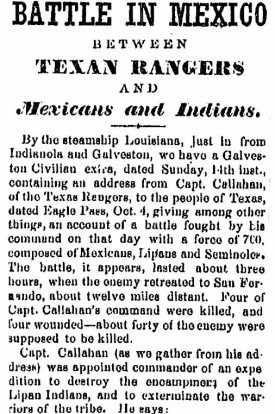

Wanted dead or alive:

“seditious” African among rebellious Natchez

Among the tribes of the Lower Mississippi Valley, the Nachez posed the most serious threat to the French colonial enterprise. A dispute over a debt that led to the killing of a Nachez villager in 1722, at the hands of a guard at Fort Rosalie, escalated into a crisis following a retaliatory raid on a plantation. After suffering counterattacks on their villages, the Nachez negotiated a peace with colonial authorities, who demanded, in addition to the scalps of several insurrectionary warriors, that the tribe “bring in dead or alive a negro who has taken refuge among them for a long time and makes them seditious speeches against the French nation and who has followed them on occasions against our Indian allies.”

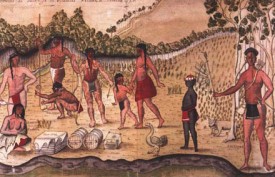

Drawing of the Savages of Several Nations, New Orleans, 1735, by Alexandre de Batz

The child of African descent in the right foreground prefigures the “intercultural collusion” later manifested in the Mardi Gras Indian tradition, while the woman kneeling on the left reveals that Indians shared with Africans the experience of subjugation under colonial rule. Next to her de Batz wrote “Renard Sauvagesse Esclave” or “Fox Indian (Female) Slave.”

The Choctaw — having assumed a position economic and political advantage among tribes engaged in regional colonial trade — were the primary Indian allies of the French. Together they mounted a retaliatory campaign against the Nachez when hostilities, triggered by the prospect of further encroachment on Nachez lands, flared anew in 1729.

In a carefully planned ambush of colonial outposts on November 28, according to Usner, Nachez rebels killed 237 men, women and children. They also captured 300 black slaves in addition to some 50 white women and children.

“Over the months of conflict that followed…,” Usner writes, “colonial authorities suppressed collaboration…between Indians and slaves with extreme force…. As feared by slaveowners, many of the African American slaves taken from the upriver concessions during [the attack] did serve as allies, more than as hostages, of the Nachez rebels.”

Joined by some 500 Choctaw warriors, the French practically obliterated the Nachez. Three black slaves “who had taken the most active part in behalf of the Nachez,” reported Father Mathurin le Petit, a Jesuit missionary, were given to the Choctaws and “burned alive with a degree of cruelty which has inspired all the Negroes with a new horror of the Savages, but which will have a beneficial effect in securing the safety of the Colony.” (Surviving Nachez warriors would, however, continue to wage sporadic guerilla warfare against the French along the banks of the Mississippi.)

Well before Coacoochee arrived on the scene, New Orleans had established itself as a multicultural entrepôt with Dionysian propensities, largely aloof from the mainstream of American Anglo-Protestant culture. It became, simultaneously, a center of the slave trade and, thanks in part to its Latin-Catholic heritage, a socially permissive place where the bloodlines of different races mixed and slaves were allowed to assemble on Sundays and partake in traditional African customs.

Alice Dunbar-Nelson

Echoing the recollections of Jelly Roll Morton, her fictional account makes clear that before turn of the 20th century, Mardi Gras Indians presented an arresting spectacle that fascinated curious onlookers in much the same way the African-derived drum-and-dance festivities had done generations earlier at Congo Square.

Photographer unknown (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

But if a remarkable ethnic diversity made New Orleans an exotic and intriguing society, it also bred fears and hostilities. Amidst racial tensions and periodic prohibitions against wearing masks — initially applied to slaves and free people of color — Mardi Gras — a European tradition transplanted to Louisiana by French colonizers — offered a temporary escape from rigidly defined roles and boundaries. On this day — the culmination of the Carnival season of merriment and make-believe before the penitential devotions of Lent — subversions of the normal order were de riguer. Away from pageantry staged by the dominant white culture, men of African and mixed-race descent began transforming themselves into free-spirited warriors “to disguise their own defiance and prowess behind an acceptable mask of wild Indian behavior,” as Usner puts it.

There was no mistaking the intensity of demeanor exhibited by the maskers. Usner, whose research was funded in part by the Historic New Orleans Collection, cites Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s short story “A Carnival Jangle.” Published in 1895, it depicts a Mardi Gras gathering in Washington Square — downriver from the French Quarter, in Faubourg Marigny — where blacks performed “a perfect Indian dance.” Spectators filled the square “to watch these mimic Redmen, they seemed so fierce and earnest.”

As a child growing up around the turn of the 20th century, Jelly Roll Morton thought Mardi Gras Indians were real Indians. In reminiscences with folklorist Alan Lomax, the Creole pianist and jazz composer described the Indians as “one biggest feats that happened in Mardi Gras. Even at the parades with floats and costumes that cost millions, why, if the folks heard the sign of the Indians

Ungai-ah!

Ungai-ha!

— that big parade wouldn’t have anybody there: the crowd would flock to see the Indians….

“They would dance and sing and go on just like regular Indians, because they had the idea they wanted to act just like the old Indians did in years gone by and so they lived true to the traditions of the Indian style,” Morton, who himself claimed to have masked as a Spy Boy, explained to Lomax.

The mythology of “masking Indian”

If there were always elements of theatricality and play to “masking Indian,” underlying the “performance” was a deeper meaning having more to do with channeling warrior/ancestral spirits and paying ritual homage than mere imitation or parody, as implied by the Buffalo Bill theory of Mardi Gras Indians.

Members of the Yellow Pocahontas Mardi Gras Indians, 1942

Over time, the headdresses reminiscent of Plains Indians regalia and typically made from turkey feathers would give way to more elaborate “crowns” featuring colorful profusions of dyed ostrich plumes and marabou (stork) feathers procured at considerable expense from specialty suppliers.

Unknown Works Progress Administration photographer (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

The late Robert Nathaniel Lee, a k a Big Chief Robbe (pronounced Ro-BEE), first put on an Indian suit in 1929 and over the course of thirty-three years of masking served as chief of four different tribes, including the Creole Wild West and the White Eagles. “It all started when young men ran away from their masters and lived with the Indians and as Indians,” he recalled in a 1996 interview with Lynne Jensen of the New Orleans Times-Picayune. “After slavery, they began to spread out, but they never forgot the tribes they lived with….

“At first,” he went on to note, “the Native Americans thought we were making fun of them. But they found out better.”

Plains Indians are often cited as a source of inspiration for Mardi Gras Indians. Sporting feathers and a beaded band across the forehead, the headresses or “crowns” of Mardi Gras Indians photographed in early decades of the 20th century resembled the “war bonnets” of Plains Indians. The decorated aprons characteristic of Mardi Gras Indian suits also may have owed a stylistic debt to the Plains tribes.

But no one really knows how the earliest Mardi Gras Indians adorned themselves, or whether the Plains Indians in the Buffalo Bill show influenced the regalia of New Orleanians of color who masked Indian in the late 1800s. What is clear is that Plains Indians conformed to the popular image of Indians native to areas west of the Mississippi River as “wild” and warlike, and that this “Wild West” stereotype — applied to tribes like the Sioux, Apache and Comanche, and reinforced by the Buffalo Bill show — would likely have had a certain inherent appeal to Mardi Gras Indians including, possibly, members of the Creole Wild West.

N. Orr’s engraving of Black Seminole Chief Abraham, published in 1848 in The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War by John T. Sprague

He made a name for himself as interpreter for, and advisor to, the Native American Seminole leadership.

The Seminoles, by comparison, have been largely overlooked as an influence on Mardi Gras Indians. This is surprising considering that, in the 1830s and 1840s, New Orleans served as a transshipment point for thousands of Seminoles during their removal to Indian Territory in the West. Their reputation — as fearsome warriors who put the hurt on soldiers and volunteer militiamen in Florida — preceded them, and their public presence in the Crescent City caused something of a sensation, attracting considerable notice in local newspapers. Their flamboyant regalia turned heads, moreover, as did the fact that the blacks among them weren’t submissive. Some, in fact, held positions of tribal influence — conveyed not only by their dress, commanding bearing and physical stature, but also by their roles as interpreters and advisors to Seminole headmen.

But most importantly, no Amerindian tribe more fully embodies the mythology of Mardi Gras Indians. For Seminoles not only symbolized fierce resistance to white domination but also provided refuge to runaway slaves en masse. This African-Indian collusion greatly antagonized those with a vested interest in the plantation economy of the South — and helped ignite what became the most costly “Indian” war ever waged by the United States.

Origins of the Seminole Wars

The Seminoles and Black Seminoles were, indeed, slaveholders’ worst nightmare come true. For if French colonizers in Mississippi and Louisiana had dreaded the prospect of runaways entering into military alliance with Indians, Spanish authorities in Florida condoned if not encouraged it as a means of undermining British and American colonial ambitions.

Reports by Spanish authorities of blacks arriving in Florida date back as far as 1688, according to Rosalie Schwartz’s monograph Across the Rio to Freedom: U.S. Negroes in Mexico — before the formation of the Seminole Tribe. The Spanish welcomed the immigrants, promising them protection from their British subjugators. “Large-scale slaveholders in their own right, the Spaniards were not necessarily motivated by sympathy for the Negroes enslaved by the British,” notes Schwartz. Rather, amidst an inter-colonial struggle for control of the fur trade and dominion over Indians and territory, the Spanish viewed the new arrivals as prospective military colonists.

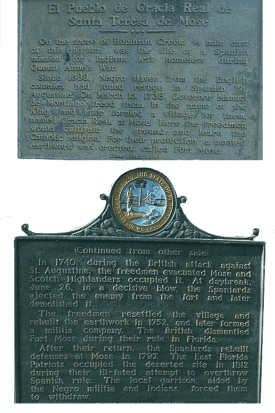

Plaque commemorating Fort Mose in St. Johns County, Florida

In 1812, annexationist forces known as the East Florida Patriots, occupying the site during an ill-fated attempt to overthrow Spanish rule, were forced to withdraw after bring confronted by Spaniards “aided by the Negro militia and Indians.”

Photos by Ebyabe (via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1738, writes Schwartz, “liberty was granted to Negro fugitives who had been held as slaves by Spanish citizens of St. Augustine, despite the angry protests of the owners.” This resulted in the establishment of a settlement for the fugitives near St. Augustine. The first free black community in North America, Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mosé boasted a militia occupying a moated earthworks called Fort Mose. Word of the settlement, and of the liberties granted under Spanish rule — blacks could own arms and property, choose their own leaders and travel at will — filtered back to southern British colonies, fueling dreams among the enslaved of escaping to Florida.

Meanwhile, tensions were brewing within the region’s most powerful indigenous confederation — the Muscogees, known to English speakers as the Creek Confederacy. Around 1750, according to Coacoochee’s Bones: A Seminole Saga by Susan Miller, a man named Wakapurchase, a k a Cowkeeper, withdrew from the Muscogee confederacy and moved his people southward into Florida. Other bands followed, motivated by factors such as disaffection with the Muscogee chiefdom, resistance to European influence, and the prospect of available land with abundant hunting and fishing.

Over time, these groups of migrant Muscogees would form a new confederation. They became known as Seminole, which — as Kevin Mulroy points out in his book Freedom on the Border: The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila, and Texas — “appears to have been a corruption of Cimarrón, a Spanish word for runaway or maroon.”

“These Indians were runaways themselves, refugees from war and oppression, exiles in a strange land,” Mulroy observes.

The Spanish welcomed them as a buffer against encroachment by British and, later, American colonists, and encouraged runaways to seek refuge in Seminole villages. By the 1830s, notes Miller, Seminoles owned black slaves and even those who didn’t may have “believed in a racial hierarchy.” Nevertheless, a genuine affection between the races developed as evidenced by the fact that Seminoles refused to sell their slaves to whites or other Indians.

A system of tribal vassalage

Whether blacks were claimed as slaves or regarded in some quarters as potential slaves, the form of slavery practiced by the Seminole was relatively benign. According to Miller, “Seminole slaves often lived in towns with free Africans, where they dressed as Seminoles, farmed and paid a share of their crop to their masters, hunted with guns, and enjoyed great autonomy.” The black and tribal villages dotted the banks of the Suwannee River, in north-central Florida.

“The Seminole-owned Africans were given tools and instructed to build huts of their own, in villages adjacent to but separate from those of the Indians,” writes Jeff Guinn in Our Land Before We Die: The Proud Story of the Seminole Negro. They could own land and livestock, choose their own leaders, and maintain a cultural identity distinct from that of the Seminole. “On a daily basis, they were as free as the Seminole themselves.”

In their relations with blacks, whether free or slave, the Indians may have taken a cue from the Spanish, whose idea of bondage was far less onerous than the system enforced by English and French colonists. Similarly, the harsh slave codes of other slave-owning tribes, notably the Creek and Cherokee, tended to mirror the practices of the British and Americans, with whom they maintained relations. “The Indians’ lenient tribal system of vassalage suited Spanish aims perfectly,” Guinn observes. “The blacks would be part of the Seminole, and the Seminole could help fight Americans if and when it became necessary. By aligning the Indians and Africans, Spain increased its defenses without having the responsibility of providing for the runaways.”

Early 20th century photo postcard showing a dilapidated slave block at what had been the biggest slave market in the South, at the Old St. Louis Hotel in New Orleans

The woman in the photo, according to the caption, “was sold for $1500.00 on this same block when a little girl.”

Those defenses were put to the test beginning around 1811. Along the Florida frontier, antagonists had been staging cross-border raids. Black slaves were forcibly taken from whites as well as from indigenous peoples. Besides encouraging Creek raids on Spanish colonies, settlers in Carolina and Georgia lobbied Washington to annex Spanish territory and return captured runaways to their owners. “Blacks who couldn’t be claimed would be handed off to slavers and sold in the markets of New Orleans and Charleston,” notes Guinn.

Faced with the prospect of re-enslavement, the blacks affiliated with the Seminole showed no restraint against annexationist forces responding to attacks on American plantations in eastern Florida. In alliance with Seminole warriors, they repelled an American attempt to eradicate Seminole and Black Seminole towns on the Alachua Plain.

“The savagery with which the Seminole Negro fought astounded the Americans…,” according to Guinn. “Word of America’s defeat spread to the Southern plantations. It conjured the worst fear among slave owners — armed blacks willing and able to kill whites…. Unless something was done immediately about the Seminole and their black allies, word of their prowess would spread throughout America’s slave community and ‘bring about a revolt of the black population of the United States,’ ” as the leader of the so-called “Patriot” forces wrote in a letter to Secretary of State James Monroe.

Andrew Jackson’s military “glory days”

In the ensuing First Seminole War, Andrew Jackson added to his credentials as a revered field commander. He was already a frontier hero for having led a successful campaign against rebellious Creeks in 1813-1814. The resulting Treaty of Fort Jackson displaced many tribespeople, opening up huge swaths of Alabama and Georgia to Anglo settlement. In 1815, “Old Hickory” made his famous, victorious stand against the British in the Battle of New Orleans — which turned out to be the final battle of the War of 1812 — forever securing his place as one of the city’s most celebrated figures.

His final engagement in the First Seminole War came in 1818, leading an overwhelming force of 1,500 soldiers and almost 2,000 Creek warriors. To buy time for occupants of native and black villages retreating into swamps in advance of the onslaught, two hundred or so Black Seminoles stayed behind to engage Jackson’s forces, at a heavy cost. “Jackson ordered his men to sack and burn the maroon and Indian villages,” Mulroy recounts, “bringing to an end what he later termed ‘this Savage and Negro War. ’ ”

It was largely on account of Jackson’s relentlessness in Florida that, in 1819, Spain ceded to America all of its lands east of the Mississippi in exchange for $5 million and American promises not to interfere with Spanish dominion over Texas. Riding his military triumphs all the way to the White House, Jackson showed no sympathy for indigenous peoples, advocating for the use of whatever means necessary to relocate them west of the Mississippi River. As president, he signed the Indian Removal Act into law on May 28, 1830.

Frederick Coffay Yohn’s Andrew Jackson During the Battle of New Orleans, circa 1922

Following successful military campaigns against Indians in the Lower Mississippi Valley and Florida, his heroic defense of New Orleans against the British solidified his stature as future presidential material, especially among those desirous of seeing frontier lands opened up for white settlement.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. ~ (Digital ID cph.3g06222)

The government wasted little time in pressing for the removal of the Seminole to a section of Indian Territory dominated by the Creeks. Leaving behind ancestral burial grounds would be bad enough. But to acquiesce would also mean living with enemy neighbors on land of questionable value. If the Americans had their way, the Seminoles would, in effect, become a subordinate part of the Creek Nation — a bitter prospect for a people wishing to preserve their tribal identity and independence.

And what would become of the Black Seminoles in Indian Territory? Surely the Creek wouldn’t let them own guns and enjoy the kind of autonomy allowed by the Seminole, for doing so would only highlight for Creek-owned slaves the inhumanity of their own position. The specter of harassment and abduction by not only the Creek but also unscrupulous white slave traders, who were prone to making fraudulent claims, loomed large.

Some historians have suggested the black maroons decisively stiffened Seminole resolve to fight against removal. Certain black leaders had in fact gained positions of influence among Seminole chiefs, making themselves more or less indispensable in a diplomatic capacity by virtue of their language skills. (The most capable Black Seminole leader, John Cavallo, could speak Muscogee, English and Spanish. He was known by a variety of names, including John Cowaya (possibly a variant of kaway, an indigenous word for “horse”) and, later, John Horse.)

Seminole chiefs, no doubt, weren’t pleased at the thought of having their blacks taken from them in Indian Territory. But among all the factors weighing against emigration, the most salient consideration for the Seminoles, in Miller’s estimation, was the prospect of leaving behind the spirits of their ancestors.

Oil-on-canvas portrait by George Catlin entitled Os-ce-o-lá, the Black Drink, a Warrior of Great Distinction, 1838

After his death in 1838, he was often depicted as an exemplary “noble savage” who virtuously resisted the inevitable march of “civilization,” whereas his successor as Seminole War Chief, Coacoochee, came across in contemporary narratives as an impudent rogue and “bloodthirsty savage.”

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

“The graves of a community link the dead forever to the landscape, for the spirits of the deceased remain at or return to the site of the burial,” she asserts in Coacoochee’s Bones. “Seminole graves made sacred the soil of their homeland, and the spirits of the Seminole relatives attended the sacred ceremonies…. Coacoochee would say, ‘the moon brings back the spirits of our warriors, our fathers, wives and children.’ Leaving the family graves meant abandoning the many members of the family who had died.”

Historical distortions and

overdue props for Wild Cat

A Seminole herself, with a Ph.D. in history from the University of Nebraska, Miller writes from an indigenous-centered perspective, arguing that European and Euro-American assumptions “distort the published history of the Seminoles.” So, for example, while “Seminoles remember Coacoochee as a great leader,” she notes, “American historians treat him as a minor and aberrant figure. While ignoring or maligning Coacoochee, Americans have made a sort of cult of his contemporary Asin Yahola” — ‘Osceola’ — perhaps in part because he died in one of their prisons where their writers and portraitists could get at him….”

Coacoochee, according to Miller, was born with a twin sister sometime between 1808 and 1816 at a lake on the Oklawaha River, in east-central Florida. “Coake means bobcat,” she explains, “and chee is a diminutive suffix, and so the name Coacoochee, translated literally, might mean ‘little bobcat’ or something like ‘Bobcat, the Younger.’ ” To Americans, he’d become known as Wild Cat. Mexicans would call him Gato del Monte (Mountain Lion).

Born into the most powerful of Seminole clans, Wind Clan, Coacoochee belonged to an elite lineage. His uncle was Nuppa, the head micco (chief) of the entire Seminole confederation. His father, Emathla (known to Americans as King Philip), was the micco of a major segment of the confederation comprised of towns along the St. Johns River.

As the Second Seminole War approached, many Seminole had been reduced to living on a swampy reservation unfit for agriculture. Although they weren’t in the path of “civilization,” the situation was, nevertheless, becoming untenable. Unable to subsist on U.S. government rations, the Indians were helping themselves to provisions and livestock from white settlements.

With pressure to implement the removal policy building in Washington, the various leaders of the Seminole communities were, as Miller relates, “divided over whether to comply with the invaders’ exorbitant demands or to resist at a cost that might prove to be greater.” Coacoochee’s father was in the militant faction, leading raids on St. Johns River plantations around Christmas 1835.

Dade Massacre monument at the St. Augustine National Cemetery

According to the marker on the tomb, all but two of the 106 men under the command of Major Francis L. Dade died in the ambush, which came just three days after the assassination of a U.S. government liaison to the Seminoles — events that marked the beginning of the Second Seminole War.

Photo by Ebyabe (via Wikimedia Commons)

John Caesar, a black Seminole, had clandestinely spread the word among local slaves that a campaign was imminent, according to Kenneth W. Porter in The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People. As if on cue, when the rampage began, they “swarmed to the Seminoles by the hundreds, painting their faces to symbolize their new allegiance and participating in the plunder and destruction.” Then on December 28, at Fort King, Arpeka, a k a Sam Jones, assassinated the U.S. government’s liaison to the Seminoles.

“Meanwhile,” relates Mulroy, “fifty miles away, north of the Withlacoochee River near the Great Wahoo Swamp, the black guide Louis Pachecho led a relief column under Major Francis Dade into an ambush of Africans and Seminoles. The allies annihilated the infantry unit, killing Dade and ninety-five of his command, the maroons returning later to mutilate the bodies of the victims. The ‘Dade Massacre,’ as it subsequently came to be known, merely marked the beginning of massive casualties on both sides.”

A “fine-looking fellow” —

and a ferocious antagonist

By 1836, Coacoochee, then a young adult, was taking part in Seminole raids in eastern Florida. It wasn’t long before he acquired a reputation among whites as a terrifying bogeyman who took pleasure in depredations. Miller cites a letter written by an American doctor in September 1837:

“This Coacoochee is a fine looking fellow and one of the most ferocious in the whole nation. Never did I see a savage whose countenance was mark’d with more daring and ferocity. Fearful are the stories of his cruelty. He himself relates stories where he has knocked the brains of children against logs and trees, scalp’d their parents and fir’d [burned] their houses….”

As a young officer who served as an aide-de-camp to top Army commanders in Florida, John T. Sprague came to know Coacoochee personally around 1841, when the warrior-chief was making “friendly” visits to U.S. outposts. After the war, Sprague authored the book The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War, published in 1848. Among his observations about Coacoochee:

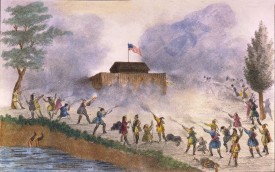

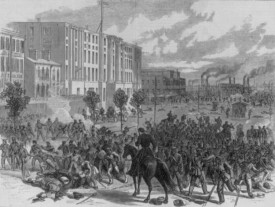

Lithograph published in 1837 by T.F. Gray and James entitled Attack of the Seminoles on the Block House

American forces were on the defensive in the early stages of the war, as the Seminoles and their black allies quickly gained a reputation as formidable foes determined to resist removal to Indian Territory in the West.

“War to him was a pastime. He became merry by the excitement, and more vindictive and active by its barbarities, and the inefficiency of the enemy. When being pursued through the deep swamps, he has stood at a distance and laughed at and ridiculed the soldiers floundering with their arms and accoutrements in mud and water. With a few followers who adhered to him for his bold achievements and success in plundering, he ranged through the country, going from one part to the other with a fleetness defying pursuit.”

If their superiority in manpower and armaments left something to be desired against the stealth tactics of the Seminoles and their tenacious black allies, the Americans could at least point to progress in the removal effort. Some elements of the Seminole confederation had decided to cooperate. In 1836, 406 Seminoles under chief Holata left Florida. They crossed the Gulf of Mexico and, in New Orleans, boarded another steamship to take them north. Conditions on the vessels were deadly. By the time the party reached Little Rock, notes Miller, 25 among them had perished.

In Florida, the American commander, Thomas S. Jesup, under intense pressure to expedite removal, decided on a bold démarche. Although the Seminoles and their black allies were united in opposition to a common foe, he realized, their interests weren’t identical. The blacks were, fundamentally, more immediately concerned with avoiding enslavement under strict masters than receiving material provisions and monetary annuities from the white man’s government.

In March 1837, Seminole leaders agreed to a capitulation of the Seminole confederation. Hostilities ceased, and the Indians and blacks began making their way to an emigration camp at Tampa Bay. The Americans were jubilant.

Key provisions of the arrangement related to the Black Seminoles: “Major Gen Jesup, in behalf of the United States, agrees that the Seminoles and their allies, who come in and emigrate West, shall be secure in their lives and property; that their negroes, their bona fide property, shall accompany them to the West…”

Slave owners and traders went ballistic on Jesup for having agreed to allow so many fugitive blacks to escape their clutches. Backpedaling, the general began pressuring Seminole leaders to surrender slaves who’d fled during the war. Florida planters, meanwhile, showed up at the relocation camp looking for runaways.

In June, militants rallied to strike a blow against conciliation with the whites. Coacoochee, Osceola and John Horse organized a raid on the camp, absconding with detainees who were being held as a condition of the truce. As hostilities resumed, American frustration with the cost and progress of the war effort came to a boil. “With power enough to blow up the world, and money, cannon and guns enough to whip the best nation in Europe, we have been baffled in all attempts to conquer a few starving Indians,” huffed the New Orleans Daily Picayune in October 1837.

The Great Escape

With his peace plan in tatters, Jesup became determined to seize the abductors and other Seminole leaders by any means necessary. A surprise raid on an Indian encampment nabbed King Philip. About a month later, in late October 1837, the Americans scored an even bigger haul.

Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine

Coacoochee’s Houdini-esque escape from this, the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States (construction began in 1672), reenergized the Seminole resistance at a point when the Americans believed enemy “war spirits” had finally succumbed to defeat.

Public domain via the Historic American Buildings Survey and Wikimedia Commons

While in custody, King Philip had agreed to send out runners with instructions for his son to come in for negotiations. Visiting the U.S. command under a flag of truce, Coacoochee was detained. There are different versions of what happened next. Jesup may have let him go back out to parlay with his comrades about complying with American demands, making it clear that his father would pay a price if he didn’t return.

In any case, a new delegation, which included Osceola and John Horse, came forward for peace talks. Accounts differ about whether Coacoochee was present when, again in violation of a flag of truce, a formidable American force emerged from hiding to surround the delegation’s encampment. The surprised warriors, outgunned and outnumbered, didn’t even try to fight. “Thus was the most notorious treachery of the Second Seminole War carried out,” writes John K. Mahon in History of the Second Seminole War 1835-1842. Jesup could report to his superiors that “nearly all the war spirits of the Nation” were in custody. However, notes Mahon, “[a]ny confidence they [the Seminole headmen] had felt in the word of the white leaders was utterly shattered.”

Coacoochee, Osceola and John Horse found themselves imprisoned in an old St. Augustine fortress, Castillo de San Marcos (called Fort Marion by the Americans), sharing a cell with, among others, King Philip. The only sunlight came from a narrow aperture in one wall, fifteen feet above the floor. Somehow the prisoners, presumably by standing on one another’s shoulders, were able to reach the opening and dislodge one of the metal bars running through it. “Even without the bar,” according to Porter, “the exit was exceedingly small — only about eight inches wide.”

One by one, the determined captives, after fasting for five days while awaiting a moonless night, contorted their way through the opening and along a five- or six-foot passage leading to the exterior of the fort’s wall. It was a long drop down to the deep ditch below, but the escapees were able to lower themselves most of the way by using a rope braided from strips of canvas bags that had served as their bedding. (One end of the rope was tied to the remaining bar in the window.)

“Eventually,” writes Porter, “twenty people stood next to the moat, among them Wild Cat, his two brothers, John Cavallo and two women. They were nearly naked, virtually unarmed, and hurt from being cut by the hard rock. But they were free.”

(Details of the escape came from Coacoochee himself, as related in Sprague’s history. After examining the historical record, Porter found no reason to doubt the chief’s veracity and concluded, in an article for the Florida Historical Quarterly in 1944, that Coacoochee was “not only a great warrior, but also a great storyteller.”)

Not all of the prisoners, alas, made it out. Apparently Osceola was too ill, and King Philip too old, to perform the physical feats required of them. They were transferred to Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island off the coast of South Carolina. Osceola died there while in custody, not long after having sat for a portrait by painter George Catlin. (The official cause of death was tonsillitis complicated by an abscess, although Catlin maintained that, in fact, he had died of a “broken spirit.”) Sent to join the Seminoles in Indian Territory, in 1838, King Philip died on his way from Fort Pike, in Louisiana, to Little Rock.

After his escape, in November 1837, Coacoochee became the military leader of those Seminoles still holding out against removal. “For three more years,” notes Miller, “he and a few of his associates would hold that resistance together.”

He had to do so largely without the military support of the Black Seminoles. Shared experiences, mutual respect and common goals had, by all accounts, made him and John Horse close comrades. They were brothers in arms, having shared dual command in the largest and bloodiest clash of the war — the Battle of Lake Okeechobee on Christmas Day 1837, with John Horse leading the blacks.

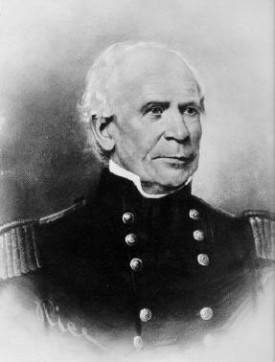

General Thomas S. Jesup

Seeking to divide the Seminoles as a military force and expedite an end to the war, he promised John Horse and his black tribesmen emancipation and protection in Indian Territory.

But in early 1838, General Jesup effectively drove a wedge between the Seminoles and their allies. “In direct contradiction to his earlier treaty with the Seminoles,” Mulroy writes, “Jesup began to offer freedom to the blacks if they would separate from the Indians and surrender.” Despite lacking the requisite statutory authority, he promised John Horse and his people — “perhaps four-fifths of whom were either runaways or their descendants and still legally slaves,” notes Mulroy — emancipation and protection in Indian Territory. In theory, not even lenient Seminole chiefs would be able to enforce claims to be their masters.

Jesup’s gambit worked. A steady exodus of black tribesmen began heading west via New Orleans. They were usually accompanied Seminoles who had either been captured or decided to give up the fight against removal.

A “noble savage” mythologized

All the while, newspapers were feasting on the rich bounty of exploits, intrigues, personalities and policy debates generated by the war. As Coacoochee was poised to emerge as the most dramatic Seminole figure in the Florida conflict, writers were busy mythologizing Osceola. His image conformed to the white man’s trope of the “noble savage” who virtuously resisted the inevitable march of “civilization.” “Although the war went relentlessly on to drive his people out of Florida,” Mahon observes, “Osceola became to many Americans a symbol of the patriotic chief fighting for the land he loved.”

Coacoochee’s image, by contrast, could not possibly be distilled in such a neat, tidy package. In contemporaneous American narratives — “hardly any Seminole commentary on Coacoochee exists in print,” Miller notes — he’s seen in a dizzying myriad of guises: charismatic leader, spellbinding orator, visionary diplomat, gifted mystic, ruthless killer, vainglorious showboat, impudent rogue and trickster, and flawed, mercurial firebrand “given to dramatic acts and alcoholic episodes,” as Miller puts it.

His was, in the final analysis, a leader of extraordinary ability. As General Jesup told the secretary of war, “He is decidedly the most talented man I have ever seen among the Seminoles, and should, and no doubt will, be the principal Chief of the Nation….”

Coacoochee initially gained fame as a military antagonist, with his public persona shaped, in large part, by American soldiers’ reports, journals and letters. “A newspaper would run a soldier’s personal letter or a passage from his journal,” Miller explains, “and then another newspaper would reprint it. Thus the news of Coacoochee reached many Americans, and his reputation grew.” Rounding out the picture are firsthand reports of journalists in Florida, New Orleans and beyond.

Physical descriptions of the chief often mention his handsome features and penchant for flamboyant attire. An army surgeon remarked, “Coa-curhee has the countenance of a white man — a perfect Apollo in his figure — dresses very gaudily, and had more than the vanity of a woman.” Sprague, the Seminole War officer and historian, describes him as “well proportioned, with limbs of the most perfect symmetry. His eye is dark, full and expressive, and his countenance extremely youthful and pleasing. His voice is clear and soft, speech fluent, and his gestures rapid and violent. With a mind active and ingenuous, clear and comprehensive, he carried into all his measures, spirit and influence; governing his band in a firm, but politic manner.”

“All white observers conceded his good looks,” notes Mahon, “but some thought him ferocious looking… He was perfectly aware of the impact of his own appearance.”

Dressing to impress

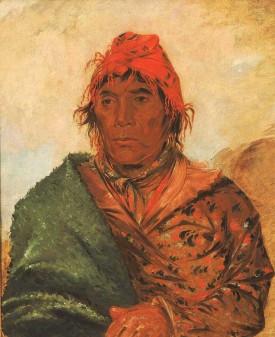

Portrait of Coacoochee’s relative Nogusa Emathla Tustenuggee, a k a Grizzly Bear, from Report on the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey (1857-1859) by William H. Emory

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Seminole regalia is the turban, often (although not in this particular case) adorned with plumes.

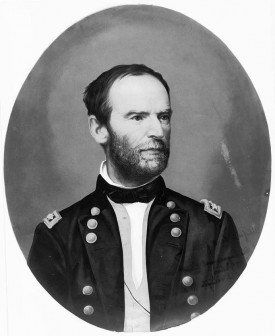

Especially when making visits to U.S. outposts during suspensions of military operations, he liked to present himself with the utmost effect. A young second lieutenant named William Tecumseh Sherman, later to gain fame in the Civil War, recalled, in his memoirs, escorting Coacoochee to Fort Pierce in the spring of 1841. The young officer headed out with eight or ten mounted troops. Coacoochee’s interpreter, Negro Joe, led them to a hammock where the chief and about a dozen of his warriors were chilling out.

“They all seemed to be indifferent, and in no hurry” to take up an offer to talk with Sherman’s “big chief,” Major Thomas Childs. Sherman instructed one of his men to secure the Indians’ rifles, which were leaning against a tree. “Coacoochee pretended to be very angry, but I explained to him that his warriors were tired and mine were not, and that the soldiers would carry the guns on their horses. I told him I would provide him a horse to ride, and the sooner he was ready the better for all.”

But Sherman and his men were made to wait while Coacoochee bathed in a pond before taking his time changing into suitable attire. As described by Sherman, he dressed in “buckskin leggings, moccasins and several shirts. He then began to put on vests, one after another, and one of them had the marks of a bullet, just above the pocket, with the stain of blood. In the pocket was a one-dollar Tallahassee Bank note, and the rascal had the impudence to ask me to give him silver coin for that dollar. He had evidently killed the wearer… In due time he was dressed with turban and ostrich feathers, and mounted the horse reserved for him, and thus we rode back together to Fort Pierce.”

Sprague also remembered the chief’s opulent regalia: “Three ostrich-plumes hung gracefully from his crimson turban. His breast covered with glittering silver ornaments, his many-colored frock and red leggings, with a sash around his waist, in which was thrust a scalping knife.”

A flair for the dramatic (à la Shakespeare)

Mahon recounts an 1840 ambush by Coacoochee and his men involving a theatrical troupe and a large baggage wagon en route to St. Augustine: “Three actors were killed, but three escaped.” Then “a yelp of joy issued from Coacoochee’s band. The captured wagon contained eighteen trunks full of theatrical costumes, grander attire than the Indians had ever seen before.”

On March 5, 1841, got up as Hamlet in one of the plundered costumes, Coacoochee presented himself at Fort Cummings for talks. “Beside him walked Horatio, while behind him crowded Richard III, very fierce of mien and very dark,” Mahon, paraphrasing a firsthand account written by one of the officers present, writes. “Others were ornamented with spangles, crimson vests and feathers, according to fancy,” the officer, Col. William Jenkins Worth, observed.

The scene that proceeded to unfold revealed an entirely different face of the warrior-chief, as if he were unmasked in a drama that couldn’t have been more poignant if it were staged. “Before the ceremonies were well begun,” Mahon writes, “a small daughter of Coacoochee’s, whom he had supposed dead — and whom the white men had treated well — came toward him holding in her outstretched palms power and bullets she had been able to collect and hide while in captivity. At this sight the chief wept openly. But his powers were not in the least weakened when it came to the talks. Even the officers, fairly hard of heart where Indians were concerned, were moved by what he said.”

Through a translator, Coacoochee delivered an oration, which Sprague, then serving as Worth’s aide-de-camp, memorialized.

“The whites… dealt unjustly by me. I came to them, they deceived me; the land I was upon I loved, my body is made of its sands; the Great Spirit gave me legs to walk over it; hands to aid myself; eyes to see its ponds, rivers, forests and game; then a head with which I think. The sun, which is warm and bright as my feelings are now, shines to warm us and bring forth our crops, and the moon brings back the spirits of our warriors, our fathers, wives and children. The white man comes; he grows pale and sick, why cannot we live here in peace? I have said I am the enemy to the white man. I could live in peace with him, but they first steal our cattle and horses, cheat us, and take our lands. The white men are as thick as the leaves in the hammock; they come upon us thicker every year. They may shoot us, drive our women and children night and day; they may chain our hands and feet, but the red man’s heart will always be free.”

A journalist reported that a “temptingly displayed” cache of silver dollars was promised to Coacoochee if he rounded up his people in preparation for emigration. “It is said that Col. Worth had a loud talk with him, to which W.C. [Wild Cat] replied ‘that his (Col. W.’s) head was muddy, and he did not understand what he was talking about.’ The fellow is a great wag. To a remarkably fine person add a sarcastic disposition and you may be enabled to form some idea of the appearance and manner of this renowned warrior. His education it appears has not been neglected, for he is familiar with our account of the creation of the world, and has given a minute description of Noah’s Ark.”

As noted in another dispatch: “This man is remarkable for the many incidents in his life, and for his bold and daring spirit…. [He] has committed more murders, and scalped more women and children than any other Indian in Florida — and this man we were to take, and did take, by the hand in friendship….

“Wild Cat’s manner, upon coming into the presence of so many officers [at Fort Cummings], and surrounded as he was by so large a body of soldiers, was somewhat confused, but he soon recovered himself, and spoke with ease, and not ungracefully. He is about thirty years of age, five feet eight inches high; well proportioned; with a calm, settled, manly face, and a dark fierce eye, beaming with intelligence.”

Buying time and making merry

During his last 18 months in Florida, Coacoochee walked an extremely fine a line between negotiating on matters of war and peace and fraternizing with the enemy; between earnest deliberation over the destiny of his people and feigning submission as a means of finagling whiskey and provisions. For the Seminole war chief, apart from instilling fear in the hearts of whites, loved a good party and had a gift for storytelling and conviviality. “Restless in his habits, cheerful and gay, he was in the habit of fabricating tales to please the Indian women, to whose comfort and relief in all things he contributed with a willing heart and hand,” Sprague relates.

Drawing on an “eventful and romantic life,” combined with a “fluency of speech and vivid imagination,” Sprague elaborates, Coacoochee would “amuse the females in camp with his dreams and remarkable adventures, giving to them the coloring necessary to impress upon the listeners his own importance and the truth of his narrative.”

In his dealings with Americans, while sometimes seeming to let his guard down when imbibing, Coacoochee employed a combination of bluster and insolence, conciliation and gestures of goodwill to keep his foes guessing as to his true intentions. Engaging in a diplomatic minuet, he seemed to realize that as long as American commanders believed he needed more time to arrange for his people to emigrate, they’d cut him slack. Weary of hostilities and under “safeguard” from Army brass, he became a presence at U.S. outposts, and his apparent willingness to cooperate raised hopes for an end to hostilities.

In May 1841, a Florida correspondent reported on a series of visits Coacoochee made to Fort Pierce, at first accompanied by 20 of his warriors. “He expressed great friendship, drank and smoked, but said little about surrendering. He is decidedly a great man, as far as drinking, dancing and fighting, according to Indian warfare, are concerned.”

Portrait of William Tecumseh Sherman by E.G. Middleton & Co.

Using words like “rascal” and “impudence” in describing Coacoochee, the young officer, who was destined for Civil War fame — or infamy, depending on your point of view — was made to wait so that the chief could bathe and dress up in flamboyant fashion for a meeting with U.S. Army brass.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons and the Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division (Digital ID cph.3c01486)

“The person of most importance next to Coacoochee appeared to be his interpreter,” a six-foot-tall black man known as Negro Joe. “The view Coacoochee had of his own importance was somewhat ludicrous,” the report continued. “Among other things he stated with the utmost gravity that it was his belief that Florida would be consumed by fire at his death.”

The officers present were “required” to treat their Seminole guests “kindly,” providing them with food and liquor. “Wild Cat and his men are the most inveterate topers that I have seen,” the anonymous correspondent declared. “They are all two-bottle men, said bottles being filled with the strongest whiskey.”

On a subsequent visit, surrender seemed imminent — or so Coacoochee led the Americans to believe. Claiming he was sick and thus unable to make the journey to the relocation camp in Tampa on foot, he received a horse and some provisions. But then his plans changed; instead of proceeding to Tampa, he returned to the fort yet again. He said he was to council with other Seminole chiefs and partake of a festivity known as Green Corn, to which he “very politely” invited the fort’s officers. To assist the deliberations, he requested (and received) “a quantity of Wy-o-min (whiskey).”

The officers were expecting Coacoochee to return with the other chiefs for a round of talks. But when he again presented himself, according to the correspondent, he instead brought news of a “misfortune”: Hogs had raided the supply of whiskey. “But the blood-shot eyes and general appearance of him and his party spoke nearly as plain as words, and informed us that if the liquor had been divided between the hogs and themselves they had secured the lion’s share.” Nevertheless, “[a] little more liquor was given them” in hopes of lubricating the path to removal.

It wasn’t long before the Americans decided they’d had enough. “He has been in at Fort Pierce 4 times since the 3rd day of May,” the Florida Herald reported after his capture in June, “and at every interview with the commanding officer of that post, he conducted himself in a very insolent manner.”

Major Childs had taken note of the fact that the Indian women and children — conspicuously absent from the parties visiting the fort — seemed to have separated from the warriors. Suspecting that Coacoochee’s band, once sufficiently provisioned, would simply disappear into the Everglades, he decided to bait a trap.

Sherman’s version of events has Coacoochee being invited into officers’ quarters “to take some good brandy, instead of the common commissary whiskey.” His cohorts were in another room when the signal was given and troops emerged with guns drawn. Within a few minutes, Sherman recalled, “the whole party was in irons.”

An Army sergeant who was present for the capture told a journalist that when “Wild Cat found himself in the custody of the soldiers, he held up his hands, without bidding, for the ruffles to be fastened upon them; observing to Major Childs at the same time — ‘I deceive you, Major, great many times, but I deceive you one time too many.’ ”

Seized along with Coacoochee were 15 Seminole tribesmen, including his father’s brother, and three blacks. Not taking any chances, Major Childs quickly had them shipped to New Orleans, where they were to catch steamer bound for Arkansas.

When their ship stopped at Key West on June 15, 1841, a correspondent for the Charleston Courier came aboard to meet “the famous Indian chief Wild Cat.” He found Coacoochee and his men in chains. “Wild Cat expressed much solicitude to me to know if I thought he would soon see his family.”

William J. Worth

After telling a captured Coacoochee that he faced execution if he didn’t induce members of his band still at large to surrender, the U.S. commander eased up to the point of offering gold pieces to the chief to go out into the field to discuss capitulation with other Seminole leaders holding out against removal.

Photo by Matthew B. Brady (public domain via Wikimedia Commmons)