As flashing for beads has evolved into a Mardi Gras pastime, “Show your tits!” has become as much a part of the lexicon as “Throw me something, mister!” But those inclined to revel in the risqué should be mindful of the fact that what was once a spontaneous and casual phenomenon undertaken in a spirit of lighthearted indulgence, has succumbed to rampant exploitation. A review of academic research on these titillating ceremonial exchanges, plus advice for those who may be tempted to partake.

Advice and insights on Mardi Gras immodesty

For better or worse, as flesh-baring exhibitionism has evolved into a traditional Mardi Gras pastime, “Show Your Tits!” has become as much a part of the Carnival lexicon as “Throw me something, mister!” Indeed, given the extensive — some would say indecent — exposure of the phenomenon in the media and through the ubiquitous Girls Gone Wild “brand,” a wide-eyed tourist could almost be excused for not knowing that flashing has never been formally legalized in New Orleans.

For the record, public indecency in New Orleans is punishable by jail time and up to a $1000 fine.

Girls Gone Wild Mardi Gras video

Once a spontaneous and casual phenomenon undertaken in a spirit of lighthearted indulgence, flashing has succumbed to rampant exploitation.

And yet, despite periodic pronouncements from city officials portending a crackdown, the police have more or less tolerated the flashing of breasts for beads. Their main concern is, after all, crowd control and public safety, not filling Central Lock-up with unruly college coeds. When flashing on a balcony causes gridlock on the street below, they’ll ask the owners to clear the balcony. As for the breast-baring revelers, they might get a verbal warning. The vast majority of arrests for “lewd conduct” involve instances of public urination and below-the-waist flashing.

It all started innocently enough. One theory holds that when float parades were banned from the French Quarter’s narrow streets in 1973, locals with access to Mardi Gras trinkets and French Quarter balconies invented a new form of entertainment to fill the void: the flesh-for-beads show. Back then, flashing was a spontaneous and casual affair, with beads a convenient medium of exchange that facilitated fun and conviviality, enabling one to quickly establish a relationship, however fleeting, with a total stranger.

Alas, that spirit of lighthearted indulgence is long gone, having succumbed to rampant exploitation. Nowadays, the voyeuristic atmosphere of Bourbon Street during Mardi Gras, swarming with professional and amateur paparazzi, is more aggressive than playful.

As Laurie A. Wilkie, a professor of anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, observes in her scholarly treatise “Beads and Breasts: The Negotiation of Gender Roles and Power at New Orleans Mardi Gras,” male voyeurs often seek to intimidate women into exposing themselves. “A woman who denies the request may find herself being booed by the crowd around her, and sometimes grabbed and jostled by disgruntled onlookers,” she writes.

Vicki Mayer, a professor in the Communications Department at Tulane University, has gotten to know a number of Mardi Gras video producers while conducting extensive field research in the trenches of Bourbon Street. For every woman who partakes in the flashing ritual, by her unscientific count, there are ten men with video cameras ready to record it. “For those who seek out the cameras,” she writes in “Letting It All Hang Out: Mardi Gras Performances Live and on Video,” an academic paper published in the Drama Review, “the desire to be looked at frequently spins out of her control. Men who swarm nude women — men who one videographer aptly called a ‘dog pack’ — publicly determine each woman’s value…. [They] not only judge women verbally, they also control the beads, doling them out on the basis of how much satisfaction they received from the show. I have seen women who do not receive the weight of their perceived worth break into tears of aggression.”

To be sure, as Wilkie points out, Carnival has long provided a forum for women to express and celebrate their sexuality, thereby contesting society’s gender ideologies and hypocritical views of femininity. And, indeed, many flashers do seem to find the ritual empowering, even addictive. “Enticing the men to solicit them becomes a form of sexual control for the women…,” writes Wilkie. “While some women perceive the display of breasts to be merely a transaction to earn beads coveted within the Carnival atmosphere, men may perceive this willingness to mean that the women are symbolically for sale, that their bodies can be purchased. Likewise, women are just as likely to perceive men as easily manipulated into providing bead wealth. Through the control of her body, a woman can exercise sexual control over men.”

Reaping rewards in the “show-me” show

Exercising sexual control over men who are easily manipulated into bestowing bead wealth? Or sending a signal to men about being sexually available?

Since there’s no denying that a fair number of revelers come to Mardi Gras with the expectation of partaking in these titillating ceremonial exchanges, we offer the following advice:

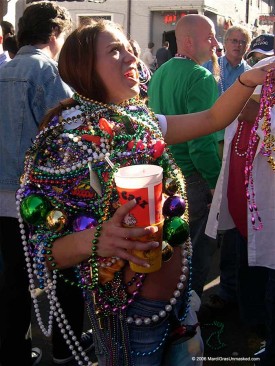

Be mindful that the wearing of beads is a form of communication — a signifier, if you will. Professor Wilkie reminds us that in a Carnival setting, beads “send a strong visual message” and represent “a form of wealth, and those people who control the beads have the potential to use them to control other people.”

If you don’t want to be solicited for flashes and subjected to leering hoots and jeers from frat boys dangling gaudy plastic charms from balconies, don’t adorn yourself with too much wampum! Wilkie notes the gender bias inherent in the fact that men with a lot of beads are perceived as having “potential power and sexual access to women,” whereas similarly endowed women are “perceived as being sexually available, for the assumption is that they have exposed themselves to obtain their beads.”

Unless you’re accompanied by male friends, think twice before exposing yourself on the street. It’s a jungle out there, and even negotiations undertaken in good faith can result in harassment.

Never allow yourself to get drawn into a frenzied mosh. Instead, if you spot some barter-worthy beads, consider negotiating with the owner discretely, on the side. Limit the audience for the display by finalizing the transaction a distance away from the hovering paparazzi.

A flash is a flash, not a striptease. Barter and flash quickly to avoid drawing a crowd. Cops are more likely to get on your case if you start putting on a show that turns heads and creates pedestrian gridlock.

While it’s generally not accepted etiquette to demand the beads be handed over before the flash, it’s often a good idea to make sure the owner of the desired strand has them off his neck and ready to hand over. If you flash and then have to wait around while he untangles the precious baubles from his neck, you may soon find yourself surrounded by a mob of jeering solicitors.

If you’re with friends when you flash, have them form a protective circle around you to prevent unwanted grabbing from the sides and behind (tip courtesy of Betty Beadwhore). If the rough and tumble of eye-level street flashing is not your style, perhaps the secure remove of a balcony will make for a more conducive experience. Many bars, restaurants and other establishments along Bourbon and Royal Streets sell balcony access, often in form of “hospitality packages” that include food and drink. Like access to skyboxes at a sports stadium, balcony privileges don’t come cheap. But, hey, it sure beats having to fend off a salivating dog pack. There’s also the added benefit that if the solicitations grow tiresome, you can always just step inside.

A team effort at Endymion’s 2008 parade

Float riders bestow booty for attention-grabbing stratagems.

Keep the “show-me” show confined to the French Quarter. Many locals take a dim view of flashing in areas where families congregate along parade routes. Not coincidentally, families tend to watch parades in areas far removed from the bacchanalian abandon of the French Quarter. And cops know this, so they’re more likely to come down hard on revelers who flash in the vicinity of children.

Contrary to a popular misnomer, you don’t have to flash to obtain good beads for free at Mardi Gras. Parades are an unbridled bounty of beads and collectible tchotchkes — if you’re willing to make the effort. Some individuals excel at getting a ton of throws from float riders without even pretending to lift their shirts. They just make a lot of noise, and know how to work it. Watch them and learn.

Remember that parade booty — especially fancy ornamental beads and cute krewe-emblemed toys — can be used to barter. Think of it as Carnival currency that can be exchanged for other throws, food and drink, bathroom access — you name it! Just get with the game and enjoy it!

If you do decide to barter for flesh, consider wearing a mask to conceal your identity. Because what’s revealed in New Orleans doesn’t necessarily stay in New Orleans. You could earn a permanent place, as the topless girl next door, in the video libraries of the folks back home in Pawtucket or in social media worldwide.

How can this happen, you might ask, when courts have affirmed a person’s right to not have his or her image exploited commercially without consent? In fact, the commercialization of flashing by video producers falls into a legal grey area that might some day have to be clarified by the Supreme Court. Producers, meanwhile, operate on the premise that their First Amendment rights trump the privacy protections claimed by those who expose themselves in public, especially at a big “newsworthy” public event like Mardi Gras where many people have cameras.

In 2002, a New Orleans judge dismissed a suit against the producers of the Girls Gone Wild video series. Three women alleged that the producers had invaded their privacy by filming them exposing themselves at Mardi Gras 1999 and using their images without permission. In siding with the producers, the judge essentially said that opting to go wild at Mardi Gras is a form of consent and that the women should have no expectation of privacy since they were on display in a public environment rife with cameras.

Finally, beware of the lethal neon-green alcoholic concoctions known as Hand Grenades, which have been known to lubricate the transformation of even the most modest girl next door into a brazenly willful exhibitionist.

MardiGrasTraditions.com