He is nothing if not an inventive instigator. Back in 1974, he was managing a bar at a pizza joint and “looking for something to do to entertain myself, to have some fun.” But what started out as an idea for a king cake party evolved into something more elaborate: a Mardi Gras ball with live music. Renown for killer costumes, bawdy high jinks and innuendo themes, MOMs Ball has become the Bacchanalia du jour for the Mardi Gras demimonde.

The birth of a bacchanal

The Underground Man as grand marshal of the Storyville Stompers; Society of Saint Anne parade, Mardi Gras 2015

Wanting to see friends in costume was a key motivation in starting what has become a Mardi Gras Bacchanalia du jour: MOMs Ball.

The Mardi Gras Underground Man recalls dressing up in a strapless blue chiffon dress, donning a blond wig and belting out a song he’d penned about sex-change operations: “Reject Your Glands,” played to the tune of Tammy Wynette’s “Stand By Your Man.” “One of the unfortunate things is I have absolutely no musical talent whatsoever,” he admits, “but that did not stop me.”

A local porno theater that billed double features on its marquee was a prime source of inspiration for the young impressario. “I had a band called Jail Bait and the Young Squirts,” he recalls. ” ‘Jail Bait’ was the first film, ‘The Young Squirts’ was the second. Great, great band.” Then there was Velvet Touch and the Pleasure Masters, put together for a Halloween party. “God,” winces the Underground Man, “it was awful.”

The Underground Man—a legendary mover and shaker in the Mardi Gras underground, he asked that his name not be used—is nothing if not an inventive instigator. Another case in point: MOMs Ball, an annual event—renowned for multiple sets of “Fish Head” music by the Radiators, costumed antics and sensory indulgence—that has become the Bacchanalia du jour for the Mardi Gras demimonde. Much like San Francisco’s fabled Acid Tests—the free-form gatherings hosted by novelist Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters back in the days when LSD was legal—MOMs Ball is an eye-opener that takes on a life of its own.

It all started in 1974, when the Underground Man was bar manager at Luigi’s, a now-defunct pizza joint in New Orleans’s Gentilly neighborhood. He recalls “looking for something to do to entertain myself, to have some fun.”

In the wake of the British Invasion, the local music scene, so vibrant in the late 1950s and early-to-mid 1960s, had fallen on hard times. “All of the clubs that I went to in high school were all gone,” recalls the Underground Man, “and no one is giving dances, nothing is happening.”

What to do? The Underground Man hit upon the idea of throwing a king cake party. In New Orleans, king cake, a coffee cake-type pastry jazzed up in Mardi Gras colors, traditionally appears on feast of the Epiphany (January 6)—also known as King’s Day or Twelfth Night (it’s the twelfth day of Christmas, the day the gift-bearing Magi visited the Christ child)—and disappears with the end of Carnival. Popular custom holds that the finder of the plastic baby (it used to be a bean) hidden in the cake must purchase the next cake and throw a party.

When the Underground Man was growing up, all of the things young Catholic New Orleanians learned socially, such as dancing, drinking and the niceties of mingling with the opposite sex, occurred at king cake parties. When the time came for the girls to choose dance partners, all of the guys, dressed in sports coats and ties, would be lined up on one side of the room. The parents hung out in another room, says the Underground Man, adding: “It’s all very awkward, like a mating ritual, and everybody did it.”

Circus Freaks at MOMs 2011

Back in the day when the Underground Man managed Luigi’s, Mardi Gras costuming had fallen out of favor among young people who’d become “too terminally hip.”

“So, we decide we’re going to have this king cake party, hire a set of parents—fake parents, you know, just to have them there”—and dust off some old 45s. There was just one problem: “Nobody’s dancing anymore, because everybody’s gone off to listen to Jefferson Airplane.” But the Underground Man had an older sister who knew how to dance, as did the older brother of one of his friends. So, a month or so before the party, everyone met at another friend’s house on Carrollton Avenue, which had a large basement, to bone up on the Jitterbug.

Soon after, a bartender at Luigi’s piped up about a Veterans of Foreign Wars hall on Franklin Avenue in Gentilly: He’d been there for fraternity theme parties. Cost to rent: about $120. There were no neighbors to worry about, and the place had custodians who’d clean up at no extra cost.

The original plan was to have the party at the house on Carrollton. Switching to the VFW hall, however, required outside financing. Thus, in order to induce people to cough up money, the original premise of the king cake party gave way to something more elaborate: a Mardi Gras ball with live music.

Before long, the Underground Man and his cohorts had rallied about 30 people to kick in $20 apiece. They had the hall lined up, but still needed a name for the shindig. It so happened that the year before, two of the Underground Man’s friends—”serious reprobates,” as he describes them—had undertaken a lark, showing up unannounced at a Gentilly barroom on Christmas night with a turkey to feed whoever happened to be on hand. Figuring that anyone who didn’t get invited somewhere on Christmas had to be either an orphan or a misfit, they waggishly dubbed it “The Orphans and Misfits Christmas Dinner.”

The duo had boasted about their exploit, but blew off doing it again the following Christmas. Someone had a flash of inspiration: Why not appropriate the name for the Mardi Gras ball? All hail the Krewe of Mystic Orphans and Misfits!

In its early years, MOMs Ball was open to anyone who showed up in costume. “Invitations” were printed up, but they weren’t required to get in the door. A core group of revelers, most of whom hung out at Luigi’s, footed the bill. Admission was free to everyone else.

“I just decided that the deal with this party is going to be that you got to wear a costume to get in,” recalls the Underground Man, “because nobody’s wearing costumes for Mardi Gras anymore, because everybody’s too terminally hip.”

The first MOMs Ball featured Paul Varisco & the Milestones, a white R&B band with Ed Volker (later of The Radiators) on keyboards. A few hundred people showed up, and the party was a hit.

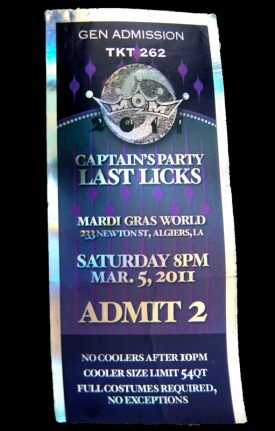

Admit to the 2011 Mystic Orphans and Misfits’ Captain’s Party, which precedes the ball and features tableau presentations and high jinks by krewe royalty and their courts.

The ball’s “Last Licks” theme was a nod to the Radiators, the beloved “Fish Head” music ensemble that had announced their intention to disband.

While not consciously setting out to spoof the courtly traditions of mainstream Carnival krewes, whose faux royalty tend to command respect, the Underground Man hit upon the idea of having Quasimodo, King of Fools, reign over the festivities. In the early years, in order to be chosen king, you basically had to have been out of work for at least half a year and owe Luigi’s $100-plus in bar tabs. In other words, says the Underground Man, “you had to be of a very questionable moral and ethical background.”

Originally, the Underground Man had wanted to go down to Camp Street (which at the time was skid row), find a wino, present him with a crown and say, ” ‘Look, how would you like to be king of this party? You get to chase women and drink all you want.’ Then throw him back out on the street the next day. But,” he adds, “it was thought to be too cruel by people who have greater sensitivity than me.”

The Underground Man, who may be the only person to have attended every MOMs Ball, emphasizes the collaborative, seat-of-the-pants nature of the whole enterprise. “This party, and most everything that I was involved in at the time, came from the collective unconsciousness at Luigi’s,” he explains. “I just happened to be the bar manager.”

The Underground Man gave up his self-described role as Krewe of MOMs “front man” about 11 years ago, and credits two friends, Woody Penouilh and Michelle Mahar, with having done the heavy lifting behind the scenes. Under different leadership, the bash has steadily grown in popularity. As a result, whereas the krewe once embraced what the Underground Man calls a “shitloose,” anything-goes ethos, it now imposes rules and has a long waiting list to join. And the ball is now an invitation-only affair.

“It has almost become the thing it sought to satirize,” observes the Underground Man. “I mean, a ticket to the MOMs Ball is as hard to get for the hip intelligentsia as a ticket to [the] Rex [Ball]. You know, it’s just a different society. It ain’t what it was.”

These days, the Underground Man’s main connection to Mardi Gras is through The Storyville Stompers New Orleans Brass Band, an offshoot of another marching ensemble he founded, The Pair-A-Dice Tumblers. He’s grand marshal of the Stompers, whose annual Carnival gigs include Phunny Phorty Phellows, a group of maskers who ride a streetcar on Twelfth Night; Krewe of Louisianians, which puts on a high-profile Mardi Gras gala in Washington, D.C.; and Society of St. Anne.

Says the Underground Man of the Mardi Gras march with St. Anne, a marching troupe whose costumes are always among the most surreal of the day: “I wouldn’t trade that for the world.”

MardiGrasTraditions.com