In exploring Mardi Gras history, there’s no tidy way to connect the dots between ancient festive customs and the modern pre-Lenten revels that occur in a myriad of guises around the world. Certainly, religious rituals associated with the mythic god Dionysus helped to get the party rolling, and over time the old pagan habits were subsumed into Judeo-Christian tradition and transplanted from Europe during the colonial era. Now mostly a secularized holiday, Mardi Gras in New Orleans has evolved from a celebration for locals into an iconic, internationally recognized spectacle.

Dionysian roots

“Journey of Dionysius” float depicting the Greek god in the 2015 Krewe of Endymion parade

As the mythic personification of the ecstatic experience, of the propensity to seek delight in the here and now, he is, in effect, the unofficial patron god of Carnival.

There is no pinpointing the origins of the celebration known today as Carnival or Mardi Gras. Indeed, because its most elemental characteristics — drinking and feasting, dancing and music, masks and costumes — extend back into the mists of time, there’s no tidy way to connect the dots between prehistoric cave paintings of dancing stick-like figures wearing animal masks and the modern pre-Lenten revels that occur in a myriad of guises in places as far-flung as New Orleans, Rio de Janiero, Venice and Port of Spain.

What can be discerned is a pastiche of customs and influences, for Carnival is nothing if not a melting pot — a constantly evolving accretion of ingredients that blend together within a framework of established conventions.

Certainly there are traces of ancient rites tied to the observance of the winter solstice. The Roman festival of Saturnalia, commemorating the death and rebirth of nature, was held in December (in honor of Saturn, the god of agriculture and civilization) and presided over by a mock king. The chance manner of his choosing — by throwing dice, drawing a lot, or discovering a fava bean or coin in a piece of cake — related to the mythology surrounding Saturn, whose reign was believed to be so just that there were no slaves or private property. Thus it was decreed during Saturnalia that all should be given equal rights, and indeed even a slave could rule. This ritual of inversion — whereby the usual hierarchies are temporarily suspended — is quintessentially carnavelesque, as is the concept of having a make-believe ruler preside over revels.

Even more fundamental to Carnival’s DNA was the ecstatic worship of Dionysus or, as he was known to the Romans, Bacchus. The Greek god of wine, Dionysus is also associated with madness, frenzy, theater and ritually induced ecstasy.

His gift of the viniculture to humankind makes Dionysus both beneficent and potentially dangerous, since wine, if consumed to excess, can inflict irrationality if not madness. Ancient Dionysian rites were religious rituals in which the god was said to possess his devotees, after they danced themselves into a trance. As The Horizon Cookbook and Illustrated History of Eating and Drinking Through the Ages says of the revels he and Bacchus inspired, “Intoxication was thought to wrest the human spirit from the mind’s control. Wine, then, became everywhere in the classical world a medium of religious experience.”

In her Great Courses lecture on classical mythology for The Teaching Company, Classics professor Elizabeth Vandiver observes that Dionysus, as “a god whose domains include possession, behavior inconsistent with one’s normal character — acting out of things that one would not normally do — is an appropriate god to be associated with a theatrical tradition in which the actors wore masks — in which an actor actually put on the face of another character before taking part in a drama.”

It also makes him the most appropriate god to be associated with Carnival. Because Carnival offers a way to step outside of oneself, to assume personae and indulge alter egos, to lose oneself in the moment and revel in collective rapture. (Ecstasy is derived from Greek words meaning “to stand outside of oneself.”) As the mythic personification of the ecstatic experience, of the propensity to seek delight in the here and now, Dionysus is, in a sense, the unofficial patron god of Carnival.

Knights of Hermes parade float entitled “The Birth of Dionysus”

Afflicted with divine madness, he roamed the world spreading viniculture and revelry, and inspired followers to wear masks in theatrical performances staged in his honor.

Also apropos of Carnival, he was a democratic, egalitarian and accessible god — his cult was universal; anyone could join in the festivities. His influence, moreover, was wide ranging. Not only did Hebrews worship him in Roman times, notes Barbara Ehrenreich in her book Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, but, “[a]ccording to the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans, the worship of gods resembling Dionysus ranged over five thousand miles, from Portugal through North Africa to India, with the god appearing under various names.” (He shares many characteristics, for instance, with the Hundu god Shiva.)

Dionysus had a special relationship with humans, for it was through him they could achieve communion with the divine and apprehend immortality directly. As Ehrenreich notes, “Dionysus cannot fully exist without his rites. Other gods demanded animal sacrifice, but the sacrifice was an act of obeisance or propitiation, not the hallmark of the god himself. Dionysus, by contrast, was not worshiped for ulterior reasons (to increase the crops or win the war) but for the sheer joy of the rite itself.”

Another aspect of Dionysus that makes him unique among the gods: He was the product of a sexual union between Zeus, the great patriarch of the Olympian gods, and a mortal named Semele. This did not sit well with Zeus’s divine consort, Hera. Disguised as Semele’s old nanny, Hera convinced Semele that she needed proof that her lover was indeed Zeus and that she should ask him to reveal himself to her in his full glory, as he would appear on Mount Olympus. When Zeus did so, at Semele’s request, she was incinerated in a puff of smoke. Whereupon, Zeus snatched the Dionysus’ embryo from Semele’s womb and implanted it in his own thigh, from whence he was born some time later. Supposedly it was because of this gestation within the body of Zeus that Dionysus turned out to be a god. “Later,” writes Ehrenreich, “Hera tracked down the grown Dionysus and afflicted him with the divine madness that caused him to roam the world, spreading viniculture and revelry.”

Dionysus’s elder half brother was the oracular god of the sun, Apollo, who is associated with light, order, reason and prophesy, as well as healing, music and the arts. Famously, in The Birth of Tragedy, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche identifies, as Vandiver puts it, “the Dionysian and the Apollonian as the two main strands of Greek thought that were constantly in tension with one another [and] productive, in many ways, of Greek culture.” This tension between the reason and order of Apollo and the irrationality and frenzy of Dionysus also provides an apt framework for understanding the dynamic of Carnival in society, wherein the “civilizing” forces of authority — both secular and ecclesiastical — are repeatedly driven to rein in the disorderly “pagan” revels.

Twelfth Night and the Christianization of Carnival

Boeuf Gras float in the Rex parade

With antecedents dating back to ancient religious festivals, the ritual slaughter of the boeuf gras (French for “fatted calf” or ox) came to symbolize the last meat and feasting enjoyed by Christians prior to the Lenten season of atonement and abstinence. In Paris, butchers would compete to see who could raise the biggest and most glorious boeuf gras. The winning beast would be paraded through the streets on Mardi Gras.

Early Christianity was itself an ecstatic religion, a suppressed cult in which enraptured dancing, carnivalesque behavior and charismatic forms of worship, i.e., speaking in tongues, were accepted. Subordinate members of the clergy claimed their own feast day, commonly known as the Feast of Fools, a sort of imitation of Saturnalia that included cross-dressing and blasphemous buffoonery.

The task of purging ecstatic and unruly behavior preoccupied Church leaders for much of the Middle Ages. Gradually, a sort of accommodation emerged: Christians could still celebrate with abandon on holy days, so long as the revels didn’t invade the sanctity of Church property. The diffuse elements of the old festive habits began to coalesce into a secularized holiday that would become known as Carnival.

The etymology of “carnival” suggests a dynamic in which pagan customs were subsumed into Judeo-Christian tradition. In its earliest usage in medieval Europe, the Latin wordcarnelevare, from which “carnival” is derived (literally meaning “to lift up” or relieve from “flesh” or “meat”), may have referred to the beginning of the Lenten season of atonement and abstinence rather than the festive customs that preceded Lent. In any case, the Church in effect rationalized Carnival as an expression of the occasional need for carefree folly. Because the day before Ash Wednesday, which marked the beginning of Lent, was a day of feasting — as symbolized by the ritual slaughter of a fatted bull or ox (boeuf gras) — it came to be known as Fat Tuesday or, as the French would say, Mardi Gras.

Mardi Gras became an “official” Christian holiday in 1582, when Pope Gregory XIII instituted the namesake Gregorian calendar still in use today. By recognizing Mardi Gras as an overture to Lent, the idea was for all the partying and foolery to be over with when it came time to observe the requisite austerities.

In medieval times, the feast of the Epiphany (January 6) — also known as Kings’ Day or Twelfth Night (it’s the twelfth day of Christmas, the day the gift-bearing Magi visited the Christ child) — evolved into a major celebration alongside Carnival. Monarchs would don their finest regalia, maybe even wager in a game of dice. Children received presents to commemorate the gifts given by the kings to the baby Jesus. In the great houses of Europe, the holiday became a glittering finale to a 12-day Christmas cycle, with elaborate entertainments featuring conjurers, acrobats, jugglers, harlequins and other humorous characters — notable among them the Lord of Misrule, whose task was to orchestrate the festivities. He is kin to Carnival’s King of the Fools (most famously represented by the character Quasimodo in Victor Hugo’s novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame).

Jesters on Fat Tuesday

Jesters in Carnival represent the license to poke fun with abandon, just as jesters in the medieval courts of Europe could speak truth to power with impunity. In New Orleans at Carnival time, omnipresent jester imagery serves as a constant reminder that true Carnival custom involves the spirit of merry mockery and reverence for the wisdom of fools.

While the Twelfth Night customs that spread throughout Europe were subject to numerous variations, one element transcended virtually every culture that observed the holiday: the choice of a mock king for the occasion. “The way he was chosen might vary,” explains Bridget Ann Henisch in her book Cakes and Characters: An English Christmas Tradition, “but it was always a matter of chance and good fortune: lots could be drawn or, in the most widespread convention, a cake would be divided. The person who found a bean, or a coin, in his piece was the lucky king for the night. Sometimes he picked his own queen, sometimes chance chose her for him, and a pea secreted in the cake conferred the honor on its finder. The temporary change in status was sustained with ceremony; the king was given a crown, the authority to call the toasts and lead the drinking and, sometimes, the more dubious privilege of paying the bill on the morning after.”

Adopting the old pagan “luck-of-the-draw” ritual dating back to Saturnalia, Twelfth Night thus became a holiday imbued with royal associations. Christians, in turn, transformed it a symbolic reenactment of Epiphany. In France, a bean-sized baby Jesus eventually replaced the bean (la feve); its discovery memorialized the discovery of Jesus’ divinity by the Magi.

Over time, Carnival became established as the season of merriment that begins on Twelfth Night and climaxes on Mardi Gras. Occurring on any Tuesday from February 3 through March 9, Mardi Gras is tied to Easter, which falls on the first Sunday after the full moon that follows the Spring Equinox. Mardi Gras is always scheduled 47 days preceding Easter (the 40 days of Lent plus seven Sundays).

If the festivities were to some degree sanctioned by the Church, according to Ehrenreich, “the uplifting religious experience, if any, was supposed to be found within the Church-controlled rites of mass and procession, not within the drinking and dancing. While ancient worshipers of Dionysus expected the god to manifest himself when the music reached an irresistible tempo and the wine was flowing freely, medieval Christians could only hope that God, or at least his earthly representatives, was looking the other way when the flutes and drums came out and the tankards were passed around.”

Modernity and the Suppression of European Festivities

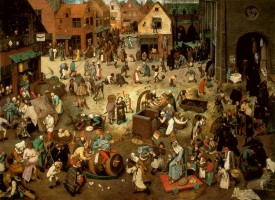

The Fight Between Carnival and Lent by Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Rich in allegorical detail, the 1559 painting contrasts somber Lenten penance, charity and abstinence from meat with Carnival feasting, masking, games and foolery. In the foreground is a mock jousting contest between figures representing Carnival and Lent. Propelled by an entourage of musicians and costumed revelers, a jolly fat man, personifying Carnival, sits astride a large wine barrel holding a long cooking skewer threaded with a pig’s head, sausages and a chicken. Bearing two small fish on a baker’s paddle, Lent — dour, pale and gaunt — sits on a church chair and advances on a trolley drawn by a friar and a nun. Following behind, children eat flatbread and burghers give alms to beggars.

This “secularization of pleasure,” Ehrenreich speculates, may help account for the unbridled, chaotic nature of pre-modern Carnivals in Europe, in which traditional conventions were suspended and the common folk ran wild in the streets — indulging in mass inebriation, insubordination and mockery at the expense of the ruling elites. It was a ribald, topsy-turvy realm that might include dancers costumed as priests and nuns, saucy comedic characters in naughty parodies of religious ritual, fools impersonating nobles, and the public harassment of Jews.

At least into the 15th century, writes Ehrenreich, “nobles and members of the emerging bourgeoisie” participated in public festivities such as Carnival “as avidly as the peasants and urban workers, and the mixing of classes no doubt enhanced the drama and excitement of the occasion.” They also partook in parallel, private revels that “had often been as uninhibited as the celebrations of the poor.”

But beginning in the 16th century, the upper classes began to distances themselves from the traditional free-for-alls. Especially in France, Carnival began to take on a more menacing, political aspect — as an occasion for protest and the fermentation of rebellion. The upper classes, meanwhile, were becoming increasingly concerned with etiquette, the art of polite conversation and “cultured” entertainment such as opera, ballet and classical music. Regarding the rowdy public escapades of the hoi polloi as déclassé, if not “vulgar,” they retreated into more refined forms of Carnival merriment such as masquerade balls.

In Europe, the Protestant Reformation, Age of Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, along with the disciplinary demands of military preparedness in an era of gun-based fighting, would take their toll on communal pleasures such as Carnival and Twelfth Night celebrations. The revels were seen as a distraction from work and a waste of resources, if not outright dangerous. “Protestantism — especially in its ascetic, Calvinist form — played a major role in convincing large numbers of people not only that unremitting, disciplined labor was good for their souls, but that festivities were positively sinful, along with idleness,” observes Ehrenreich. Obedience, self-denial and deferred gratification were the new order of the day, and surviving expressions of the old Dionysian spirit became targets for suppression.

“The Catholic south of Europe held on to its festivities more tightly than the north,” relates Ehrenreich, “though these were often reduced to mere processions of holy images and relics through the streets…. Everywhere the general drift led inexorably away from the medieval tradition of carnival.” She goes on to cite Peter Stallybrass and Allon White, authors of The Politics and Poetics of Transgression. “In the long-term history from the 17th to the 20th century…,” they write , “there were literally thousands of acts of legislation introduced which attempted to eliminate carnival and popular festivity from European life….”

Transplantation and regeneration in the New World

Society of Saint Anne maskers on Mardi Gras 2002

Traditions and customs associated with aristocratic court spectacles of Old Europe would have a lasting influence on New Orleans Mardi Gras.

Across the oceans, however, the colonies of the New World, especially Latin-Catholic outposts on the Gulf Coast, would provide fertile ground for regenerating the old rituals of collective joy. Carnival in New Orleans, in particular, would become a multifaceted extravaganza, incorporating a kaleidoscope of European, Afro-Caribbean, Native American and Mexican/Latin American cultural influences.

On the evening of March 2, 1699, French-Canadian explorer Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d’Iberville, leading an expedition on behalf of the French crown, dropped anchor at the mouth of the great Mississippi, about 60 miles down river from the present location of New Orleans. The next day, coincidentally, happened to be Mardi Gras. “The first place names given Louisiana were, appropriately, Pointe de Mardi Gras and Mardi Gras Bayou,” notes Mel Leavitt in his book A Short History of New Orleans.

Iberville’s expedition went on to establish settlements at Biloxi Bay (Mississippi) and Fort Louis de la Louisiane (Alabama), located on the Mobile River a few miles upstream from the present site of the city of Mobile. (Mobile, which calls itself the Mother of Mystics, traces its Carnival tradition to 1704, when Nicholas Langlois founded Societe de Saint Louis, a forerunner of the secret societies, or krewes, that would later institutionalize Carnival in New Orleans.)

That Carnival would sink deep roots in New Orleans speaks to the essential character of the city. “America, which makes a fetish of reason, righteousness and modernism, is among the most Apollonian of nations,” the art critic D. Eric Bookhardt once observed in Gambit Weekly. “New Orleans, which is forever unimpressed by reason or righteousness, and is mostly anti-modern, is the most Dionysian of American cities.“

In 1718, Iberville’s brother, Jean Baptiste LeMoyne, Sieur d’Bienville, established New Orleans as a permanent settlement. The French Crown commissioned a private enterprise, the Company of the Indies, to develop the colony. In 1729, Marc Antoine Caillot arrived from France to work as a clerk for the Company of the Indies.

Cancan dancer on Mardi Gras 2008

Cross-dressing for Mardi Gras dates back to the first recorded account of New Orleans festivities in 1730.

In 2004, the Historic New Orleans Collection acquired Caillot’s lengthy written chronicle of his activities in New Orleans and his travels to and from the colony. The so-called Caillot Manuscript contains the first recorded account of Carnival in New Orleans.

According to an article in the 2011 edition of Arthur Hardy’s Mardi Gras Guide, written by Lori Boyer and based on research by Erin M. Greenwald of the Historic New Orleans Collection, Calliot’s father was a footman in the household of the Dauphin, the son of King Louis XIV. As this was a time of court festivities on a grand scale — including masquerades mixing poetic verse, music and dancing, and performed by people wearing masks and costumes in accordance with a theme — Calliot was likely accustomed to aristocratic celebrations of Carnival.

He writes of being “quite far along in the Carnival season [of 1730], without having had the least bit of fun or entertainment, which made me miss France a great deal.” Arriving in his office on the day before Mardi Gras to find his colleagues “bored to death,” he proposed a Mardi Gras masking adventure to Bayou St. John. Cross-dressing as “a shepherdess, all in white,” with “a corset of white bazin, a muslin skirt, a large pannier” and “beauty marks on my face and even on my breasts, which I had plumped up,” Caillot fancied himself “the most coquettishly” turned out member of the group. His “husband” was got up as “the Marquis of Carnival” in “a suit trimmed with gold braid on all the seams.”

Folklore has it that after he became governor of Louisiana in 1743, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, assisted by a dancing master called Bebe, established society balls and banquets that would evolve into the upper-class Carnival soirees of later generations. The elements of court behavior and presentation that would become features of these balls had roots in Europe’s ancien régime. The practice of incorporating tableaux as a performance element can be traced to the mythological-allegorical spectacles of Italian festival tradition.

Carnival and the Creoles

Louisiana-born descendents of French and Spanish colonizers came to see themselves as a New World aristocracy, aloof from mainstream Anglo-American culture. Their folkways — they were devotees of music, dance, theatrical amusements and games of chance — did much to define New Orleans as a culturally exotic, socially permissive entrepôt.

Mandingo Warriors Mardi Gras Indians practicing at the original site of Congo Square

In colonial times, the focal point of Afro-Caribbean culture was the Place des Negres, later renamed Congo Square. Until it was suppressed around 1835, the public market and venue for communal drum-and-dance convocations provided continuity for African forms of festive merriment. The percussive rhythms and call-and-response chants that drove the revelry entered the vernacular of Mardi Gras and New Orleans music.

These Creoles, as they took to calling themselves, had a soft spot for Twelfth Night and the old tradition of having the finder of a bean or trinket concealed inside a cake rule over the revels. In the colonial era, New Orleans Creoles cut cake to divine royalty during a season of balls, called les bals des Rois (the balls of kings), that began on Twelfth Night and ended on Mardi Gras. As the Carnival season of merriment became more established, while upper-crust Creoles reveled at fancy-dress and masquerade balls, impresarios staged public balls catering to various strata of society.

“New Orleans simply couldn’t resist the lure of a masked ball at any time or for any reason,” writes Henry A. Kmen in Music in New Orleans: The Formative Years, 1791 – 1841. “It was always fun to dance, but to hide one’s identity behind a mask greatly heightened the thrill and broadened the range of permissible partners or possible adventures….”

In colonial times, a remarkable ethnic diversity made New Orleans the New World’s most exotic and intriguing society but also bred fears and hostilities. In 1781, a report to the Spanish colonial governing body, the Cabildo, raised concerns about people of color masking and mingling while passing through the streets in search of dance halls. Fearing that masks provided anonymity for disorderly conduct and subversive political activities that could lead to slave rebellion, the authorities forbade slaves and free people of color to wear masks, and the prohibition was extended to all masks a few years later.

Not long after the United States purchased Louisiana in 1803, masking once again had the authorities on edge. “On Jan. 21, 1806,” writes Kmen, “the city council, acknowledging that masks and disguises ‘were the means of grand disorders among us,’ proclaimed that henceforth anyone wearing a mask on the street was to be arrested, unmasked, and fined ten dollars. More than this, the council forbade all masked balls, public and private, under fine of 20 dollars against anyone giving or attending one.” The prohibition wasn’t always enforced, however.

In 1827 — thanks largely to petitioning by prominent Creoles, who saw themselves as conservators of the cultural heritage of Old Europe — the City Council lifted the ban on masking from January 1 through Mardi Gras. As street masking burgeoned, bands of musicians and ornamented carriages began joining in the processions. Elite, exquisitely attired Creole ladies were said to ride through the streets tossing bonbons to gentlemen admirers.

Also in the early decades of the 19th century, the Afrocentric performance culture of Congo Square, an area where slaves were permitted to assemble on Sundays, began to resonate in ways that would later influence the development of jazz as well as second line and Mardi Gras Indian traditions. Simultaneously strange and alluring, the goings-on became something of a tourist attraction. As a visiting missionary described the “Saturnalia” and “Congo dances” he witnessed in 1823: “Everything is license and revelry.”

A New World Lord of Misrule

Comus krewemen, with cowbells, on Fat Tuesday 2002

The prototypical New Orleans Mardi Gras krewe, Comus is forever indebted to Michael Krafft, founder of Mobile’s Cowbellion de Rakin Society and the archetypal reveler-ringleader of Gulf Coast Mardi Gras.

Carnival historians often point to the Cowbellion de Rakin Society as the key precursor of the New Orleans Mardi Gras krewe system. On a rainy Christmas Eve night in 1831, in Mobile, Alabama, a cotton broker named Michael Krafft — described in a contemporary account as “a fellow of infinite jest and…fond of fun of any kind” — apparently found himself in the doorway of a hardware store, quite likely intoxicated. He gathered up a string of cowbells and attaching them to the teeth of a rake, went on his merry way, clattering. According to this account of the night’s events, as related by Samuel Kinser in his book Carnival, American Style, Krafft, having drawn a crowd, caught the attention of a passer-by who exclaimed, “ ‘Hello, Mike — what society is this?’ Michael, giving his rake and extra shake and looking up at his bells, responded, ‘This? This is the Cowbellion de Rakin Society.’ ”

Kraff’s waggish, playful exhibitionism was at the very core of the cultural enterprise that would become Gulf Coast Carnival. On subsequent rambles, he was joined by more “Cowbellions,” and the group went on to become Mobile’s premiere Carnival organization, sponsoring New Year’s Eve masquerades and even venturing to New Orleans in the late 1830s to partake in Mardi Gras. In 1840, the krewe presented its first parade with floats depicting a specific theme: “Heathen Gods and Goddesses.” A masked ball followed.

Some of the founders of the prototypical New Orleans Carnival organization, the Mistick Krewe of Comus, had ties to Mobile and the Cowbellions. The Comus krewemen, moreover, are said to have borrowed costumes from the Cowbellions for their inaugural Mardi Gras pageant, in 1857.

South Philadelphia String Band, a longtime fixture of that city’s Mummers Parade, shown here in the 2002 Knights of Hermes parade

Did Pennsylvania’s “mummer” tradition influence the formation of Gulf Coast Carnival?

A New World Lord of Misrule, Krafft, whose name indicates German ancestry, was a native of the Philadelphia area. Kinser points out that in German communities in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, a custom called “belsnickling” took place on Christmas Eve. “Belsnickle” could refer to a noisy party or a sort of Wildman figure disguised in furry garb as a demonic version of Saint Nicolas. “Shaking cowbells at his waist or smaller bells attached to his garments and brandishing a club, whip or other menacing instrument,” relates Kinser, he’d go from house to house, “frightening children but also bestowing small gifts.”

Kinser also cites an account that has Krafft tying cowbells to his rake “for music,” and mentions a fife and drum being present for the inaugural Cowbellion romp. Such “rough” music with improvised instruments was a prominent feature of holiday masking by revelers who became known as the Mummers of Philadelphia. These celebrants, who were of northern European ancestry, took to the streets on New Year’s Day dating back to the earliest days of city — dressing in costume, using miscellaneous noisemakers and bells, banging pots and pans, and generally making a clamor as they visited neighbors after Christmas.

Generating a bit of pandemonium was, of course, characteristic of the old European Carnivals. All of which makes it reasonable to surmise that through the personage of Krafft, festive holiday customs transplanted to the New World by way of northern Europe became a key ingredient in the gumbo of Gulf Coast Carnival. It was a contrasting flavor to the contribution of the more genteel Creoles, whose revels imitated European aristocratic court spectacles.

The Age of Impudence and the birth of Comus

By the late 1830s, the notion of New Orleans Mardi Gras as a public celebration with broad appeal, as an amusing occasion for carrying on Old World tradition, was on the cusp of change. Revelers who would later become known as “promiscuous maskers,” for their irreverent and bawdy foolery, had begun to make their presence felt. On Ash Wednesday 1837, the New Orleans Picayune censoriously described a scene of unruly, racially mixed cavorting in the streets involving maskers got up as animals, circus performers and Indians: “A lot of masqueraders were parading through our streets yesterday, and excited considerable speculation as to who they were, what were their motives and what on earth would induce them to turn out in such grotesque and outlandish habiliments.”

In New Orleans during the 1850s, social changes caused by an influx of immigrants and transients, as well as racial and ethnic mixing in the streets and at public balls, were a source of increasing anxiety for the privileged class. Chance encounters among anonymous maskers put customary social and racial distinctions at risk. “Leading citizens” closely associated participation by ethnic (Irish), black and mixed-race celebrants with disorder, unruliness and sexual permissiveness — hence the term “promiscuous maskers” — and resented the fact that the upstarts were adapting the celebration to suit their own culture and purposes (thereby transforming it into a more spontaneous, uninhibited affair that was perceived as disrespectful of, if not threatening to, the prerogatives of the established social order).

Comus on Mardi Gras 2002

At the pinnacle of the old-line Carnival hierarchy, he bears a sterling silver chalice and his identity is never revealed.

Ehrenreich’s analysis of black participation in Carnival in other countries is instructive in this regard. “In both Trinidad and Brazil,” she observes, “whites responded to black participation just as elites had responded to the disorderly lower-class celebrations of carnival in Europe: by retreating indoors to their own masked balls and dinner parties, which were invariably described as ‘elegant’ by the local newspapers, in contrast to the ‘barbarous’ celebrations of blacks.” (As in New Orleans, Carnival in Trinidad originated as a white celebration, imported by French settlers.) The “disapproving accounts” of black Carnival in the Caribbean by white observers, Ehrenreich adds, consistently “downplay the artistic creativity that went into costume making and choreography, to focus instead on the perceived violence, disorder and lewdness of the events.”

There was no denying that Carnival seemed to encourage impudence among the “lower classes.” In New Orleans, their jests, pranks and brawls were offending “respectable” people, prompting some newspapers to champion the abolition of the festivities. “TheDaily Orleanian decried the racial mixing in the streets during Carnival; the Daily Crescent spread rumors of Carnival’s reported eminent disintegration; and the Bee excitedly condemned Carnival back to the “barbarous age” whence it came,” notes historian Jennifer Atkins in her 2008 PhD thesis, Setting the Stage: Dance and Gender in Old-Line New Orleans Carnival Balls, 1870 – 1920.

It was against this backdrop that the Mistick Krewe of Comus made its parading debut in 1857. In a torch-lit procession on the night of Mardi Gras — with two floats, brass bands and costumed maskers — the Comus krewemen presented “The Demon Actors in Milton’s Paradise Lost,” a theme carried through in the tableaux staged at their exclusive ball. By adopting a mythological namesake and presenting a thematic, meticulously organized street spectacle, followed by a tableau ball that was more a cultural performance (staged before formally attired guests) than a typical Carnival masquerade dance with everyone in costume, Comus established a paradigm that would be widely imitated. Indeed, the cultural practices that would come to define “modern” Carnival began with the Mistick Krewe of Comus.

Royal invention: a king of Carnival

Rex 2010

After the Civil War, businessmen and civic leaders invented a benevolent monarch to reign over a daytime parade on Mardi Gras. Rex and his queen — a debutante chosen by krewe leaders largely on the basis of her father’s prominence and her familial connections to past Rex royalty — came to be recognized as monarchs of the entire Carnival celebration.

A group of businessmen and civic leaders invented a king of Carnival, Rex, in 1872. The first Rex, Lewis Salomon, was a financier in the cotton trade who helped raise funding for the inaugural parade. In 1921, in an interview with a reporter from the New OrleansTimes-Picayune, he described a newspaperman, Edward C. Hancock, as the behind-the-scenes “big chief” and recounted a gathering at the St. Charles Hotel in the weeks leading up to Mardi Gras.

“Someone — I’m sure it was Hancock — said: ‘Now look here; why not make this Carnival a real affair?’ ”

Hancock’s role in Rex is illuminated by Errol Laborde in his books Marched the Day God: A History of the Rex Organization and Krewe, which focuses on the 60 years of Carnival following the birth of Comus. A crusading journalist with a literary flair, Hancock was a Philadelphia native who, like many young northerners in the pre-Civil War era, came to New Orleans — arguably the most cosmopolitan city in the country — to make a name for himself. After the war, he served as associate editor of The New Orleans Times, which stoked anticipation for the inaugural Rex parade by publishing tongue-in-cheek edicts and tidbits dispatched from His Majesty’s mythical realm on Mount Olympus. Hancock envisioned a unifying centerpiece for daytime festivities that would coordinate the miscellaneous groups that had been informally parading on Mardi Gras. According to Salomon, “Hancock insisted that all the promiscuous maskers and private clubs ought to be organized into a general parade.”

Rex provided a civic counterpoint to highly secretive and exclusive Comus. Adopting the motto Pro Bono Publico (for the Public Good), the Rex organization offered a tonic for a South still riven and weary from the Civil War, thereby helping to lure visitors back to the city. The highly anticipated visit of Russian Grand Duke Alexis Romanov, who witnessed Rex’s debut amid great fanfare, added a touch of royal romance to the pageantry.

The Rex krewemen introduced the Carnival colors of purple, green and gold. Via Rex’s 1892 parade, entitled “Symbolism of Colors,” they came to signify justice, faith and power, respectively.

This has an echo of the four fundamental principles by which Socrates and Cicero both said we must live our lives: wisdom, justice, courage and moderation. Rex’s inclusion of “faith” in the symbology can be seen as a nod to the Church’s incorporation of Carnival into Judeo-Christian tradition, while the conspicuous absence of moderation — the key prescription inscribed on the oracle of Apollo at Delphi — suggests Dionysian propensities. Whereas, “power” evokes the monarchical aspect of Carnivaldom as practiced by the elite in post-Reconstruction New Orleans. At the top of the hierarchy of rulers presiding over the krewe fantasy kingdoms was Comus (motto: Sic Volo, sic jubeo (As I wish, thus I command).

The Mistick Krewe of Comus initiated the practice of having a different krewe member each year assume the role of figurehead to preside over a parade and ball. In mythology, Comus is son of reveler Bacchus and necromancer Circe. In the Carnival realm, his kin would grow to include, among others, the Lord of Misrule (potentate of the Twelfth Night Revelers), Momus, Rex and Proteus — all of whom would be anointed anew annually, to reign over rarefied domains in which adventure, conquest and enchantment provided much of the thematic ballast for artistically ambitious parades and balls. Except for Rex — who, in a sense, became the public face of the old-line Carnival aristocracy — the identities of these mock rulers were strictly secret.

Carnival debutantes and the Golden Age

The 2006 Queen of Carnival and His Majesty Rex en route to the Comus ball for the Meeting of the Courts

Chosen by the inner sanctum of the Rex Organization, she is usually a junior in college at the time of her reign — 20 or 21 years old. Amidst a whirl of Carnival-related events and obligations in the weeks and months leading up to her day in the limelight — tea parties, debut parties, social calls, dress fittings and lessons in the finer points of royal protocol and etiquette — she’s supposed to keep the honor a secret.

Beginning in the 1870s, the staging of multiple post-parade tableaux in ballrooms and theaters gave way to a new style of spectacle in which the presentation of queens and maids, along with other krewe “royalty,” provided the central image. Carnival balls became vehicles for the formal presentation by krewemen of debutante daughters and granddaughters to society. For these chosen few, mastering the finer points of feminine regality and court protocol served to validate social status and establish credentials as prime marriage material. Elite families came to measure social rank based on how many court appearances their daughters made at prestigious Carnival balls.

No question, the early krewemen were capable of erudite feats of grandeur and artistry. During the so-called Golden Age of Carnival, from the 1870s through the 1920s, they went to extraordinary lengths to present pageants in which every last detail — as reflected in the costumes, ball décor and the design of the parade floats and ball invitations — would coalesce in a sophisticated evocation of a theme.

While parades of this era occasionally ventured into social commentary and political lampooning, mythology, literature, history and religion comprised the dominant source material. The balls themselves were otherworldly realms, infused with an aura of mystique and fantasy conducive to courtship and flirtation.

Only krewe members, all of whom were men, costumed and wore masks, however. “Masking allowed men to titillate their partners with an allure of the unknown,” observes Atkins in her PhD thesis. “Protected by masks, krewemen were free to pursue flirtations in a manner forbidden in everyday life. In the ‘real world,’ etiquette scripted every move and compliment to a lady, but costumed as a knight (or even as an elf or 7-foot tall pelican), krewemen escaped the confines of everydayness and joined their female partners in a romantic fantasy.”

In the early krewe pageants, like in William Shakespeare’s theatrical troupe, cross-dressing was de rigueur. As Henri Schindler explains in his illustrated history Mardi Gras Treasures: Costume Designs of the Golden Age, “every female character was brought to life by an all-male cast; no matter how delicate or feminine some costumes may appear, they were worn with delight by generations of the most prominent businessmen of New Orleans.”

A tale of two history lessons: official vs. unofficial

Reproduction of Rex’s 1882 “butterfly” king, who embodied the theme of that year’s parade, The Pursuit of Pleasure

While the erudite grandeur and ambitious artistry of their pageants cannot be denied, the early krewemen also sought to project cultural power, reinforce their elite status and proclaim superiority over “lesser mortals” who’d assumed positions of authority during Reconstruction.

Prominent non-academic New Orleans Carnival commentators tend to show considerable deference to the “old-line” krewes. Theirs is an apolitical view that generally looks askance at attempts to interpret Carnival’s evolution through the analytical lens of race and class distinctions. In this conception, the original krewemen were beneficent gallants who bequeathed an indelibly rich cultural legacy that revels in the creative indulgence of whimsy, brings mirth to multitudes and greatly enhances the allure of New Orleans. Were it not for the innovations they brought to bear on the unruly goings-on of yore, New Orleans Carnival would never have achieved its iconic renown.

All of which generally conforms to what sociologist Kevin Fox Gotham, in his bookAuthentic New Orleans: Tourism, Culture and Race in the Big Easy, calls the “official story” of Mardi Gras. In this narrative, as “passed down through generations in magazines and local newspaper editorials…, antebellum Carnival was marked by rampant lawlessness, violence and disorder. In response, enlightened citizens formed the elite Carnival krewes to bring order to this chaotic world, tame the unsavory past, and establish a more civil and humane Carnival for the enjoyment of all.”

The krewe system, according to Gotham, “established a new form of social differentiation between the ‘public’ and ‘private’ spheres of Carnival, separating activities open to the public (organized parades) from those limited to the private krewes and their guests (invitation-only tableaux balls).” In effect, “the spontaneity and free license” of the traditional antebellum festivities, in which spectators and participants closely intermingled, yielded to “the creation of new forms of social order and control,” i.e., “preplanned and scripted parades that separated spectators from krewe paraders….

“Guidebooks and advertisements henceforth would celebrate Carnival for its ability to deliver fun and entertainment in a rationally controlled and predictable fashion, conditions that are the opposite of the festive release, insubordination and transgression of the pre-modern Carnival described by Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin.”

What might be called the “unofficial” story of Mardi Gras — as explicated by Gotham and other academics like Anthony J. Stanonis, J. Mark Souther and Jennifer Atkins, as well as journalist James Gill — goes something like this:

2006 Rex float honoring the Mistick Krewe of Comus on its 150th anniversary

The illustrations on the side of the float are from one of Comus’s most famous parades, 1873′s Missing Links to Darwin’s Origin of Species, which presented animal-like caricatures of carpetbagging public figures from Reconstruction who had, in effect, inverted the “natural order” by placing a “missing link” — the mixed-race P. B. S. Pinchback in the guise of a banjo-playing gorilla — in a position of power. (Pinchback briefly served as governor of Louisiana.)

The original old-line krewemen were mostly Anglo-Protestants, including transplanted Northerners, who had economic interests in the plantation system and fought for the Confederacy. Their wounds from the Civil War ran deep, and their sense of indignation and alienation only increased during the social, political and racial upheaval of Reconstruction. Carnival became a realm where they could assert social dominance and reclaim a sense of honor. Forming secretive social clubs for the purpose of organizing parades and balls, they effectively usurped the Latin-Catholic tradition of Mardi Gras masking and appended it to reenactments of the courtly rituals of Old Europe. These annual revivals of monarchic rule enabled chauvinistic krewemen to project cultural power, reinforce their elite status and proclaim superiority over “lesser mortals” who had assumed positions of authority in the aftermath of the Civil War.

In cultivating pomp and elevating themselves as knights and kings, krewemen assumed the mantle of heroic defenders of a Romantic world symbolic of the Old South. As idealized embodiments of the realm’s genteel femininity, court queens and maids justified the krewemen’s masquerade as chivalrous protectors.

While ostensibly operating in a world of make-believe, their cultural performances sometimes had strong ideological undercurrents, reflecting the struggle to protect racial and class interests in the Reconstruction era. Notably, Comus and Momus presented the rhetoric of white supremacy in the guise of satire.

In place of grassroots, pre-Civil War revelry that was, to a large extent, racially integrated came new lines of hierarchy and racial division. Black men tended the mules that pulled the krewe floats and carried flambeaux to illuminate the nighttime parades. Formerly the domain of the promiscuous maskers, the public space of Carnival was now largely occupied by carefully orchestrated processions in which masked krewemen on fanciful floats — self-appointed arbiters of culture — towered above passive spectators. Photos of early krewe parades show crowds not in costume but dressed in what might be described as their “Sunday best.”

The high-profile krewe parades would prove to be a boon for tourism, but there was consternation in some quarters over the loss of old folkways. Gotham cites an editorial in the March 6, 1881, edition of the New Orleans Times expressing nostalgia for a time before Rex when “our thoroughfares swarmed with merry maskers from one dawn till almost the next.” It went on to lament the decline of the “riotous quality” of Carnival and critiqued the Rex parade as a “stern procession” of “splendor but no humor.”

“The old, robust laugh and the old, wild license have gone out of the Carnival of New Orleans,” the editorial observed. “This laugh and license were, we believe, the vital conditions of its maintenance.”

“Masking Indian” on neighborhood backstreets

Victor Harris, chief of the Mandingo Warriors Mardi Gras Indians, on Carnival Day 2011

An esteemed practitioner of the Mardi Gras Indian arts who taps deeply into African influences. Departing from the open-face crowns typically worn by those who “mask Indian” — a style derived from Native Americans — he wears Malian-style masks that completely cover his head.

But if “official” Carnival, as represented by krewe pageants, seemed lacking in spontaneity and abandon, the holiday, as celebrated on neighborhood back streets, still offered escape from rigidly defined roles and boundaries. As racial repression intensified in the post-Reconstruction era, hardening the color line governing participation in “mainstream” Mardi Gras festivities, organized groups of black and mixed-race celebrants masking as Indians took to the streets on Fat Tuesday.

Slaves and Native Americans intermingled from the earliest days of colonial Louisiana. They shared similar belief systems involving ceremonial communion with ancestral spirits. And both groups had in common the experience of being subjugated by the dominant culture. As racial repression intensified in the post-Reconstruction era, hardening the color line governing participation in Carnival, organized groups of Mardi Gras Indians, as they came to be known, took to the streets on Fat Tuesday. By masking Indian, they expressed ritual freedom, provided continuity to Afrocentric forms of festive performance, and paid homage to tribes that provided refuge to runaway slaves. Oral tradition places their beginnings in New Orleans as far back as the 1830s (the first documented account was in 1900).

At one time, rivalries among Mardi Gras Indian tribes or “gangs” (usually defined by neighborhoods) often turned violent. Theirs was a warrior culture largely obscure to the general public. But slowly, beginning in the 1940s, the competitive aspects of their revelry came to revolve around performance and costuming. The process of making a Mardi Gras Indian “suit,” which can take up to a year and cost thousands of dollars, brings families and communities together in a collaborative artistic endeavor. The results can be stunning: the vibrant colors of dyed ostrich, coque and marabou feathers, which recall the ceremonial attire of Plains Indians, are complimented by intricate, pictorial beadwork or sculptural (raised-relief) designs set off with dazzling arrays of crystals. A Mardi Gras Indian earns props not only through artistic skill and performance ability — singing, dancing and mastery of the protocols and dramaturgy of “playing Indian” — but also by serving as a mentor and community role model.

As the Mardi Gras Indians have evolved from a rough-and-tumble fringe element — harassed by police for parading without permits — into celebrated icons, their music and traditions have become emblazoned on the aesthetic and cultural consciousness of New Orleans and beyond. Suits by the likes of Victor Harris of the the Mandingo Warriors Mardi Gras Indians are now featured in prestigious art exhibitions, while the HBO series Treme, in which Mardi Gras Indians figure prominently, has brought the culture to a mass audience.

The National Endowment for the Arts also has recognized the achievements of Mardi Gras Indians. The NEA awarded the late “chief of of chiefs,” Allison “Tootie” Montana of the Yellow Pocahontas, a National Heritage Fellowship in 1987. Bo Dollis of the Wild Magnolias received the award, considered the nation’s top honor in folk and traditional arts, in 2011.

The uproarious revels of the Zulus

Another African-American Carnival institution, which has proven no less enduring than the Mardi Gras Indians, began in the early 1900s with a small, informal marching group called the Tramps — a raggedy lot who affected the manner of hobos on Carnival Day. The group took up an African theme after seeing a musical comedy performance that included a skit about the legendary king of the African Zulus, Shaka. The performers were African-Americans in blackface, a standard convention of minstrelsy and vaudeville. In 1916, the Tramps changed their name to the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club.

Members of a Zulu marching contingent known as the Tramps, on Mardi Gras 2010

A predominately African American krewe that has evolved from humble beginnings into a popular and iconic mainstay of Carnival, Zulu is famous for its raucous parades, coconut throws and colorful assemblage of characters.

As a prominent, and at times controversial, characteristic of the Zulu masquerade, blackface came to be interpreted as being part of a lampoon of the white man’s racial stereotypes. But when the first Zulus blacked up in the early 1900s, it was more a practical matter than a subversive statement. The early members couldn’t afford to buy masks. A five-cent tube of face paint did the trick.

The braggadocio inherent in the title of the skit about Shaka, “There Never Was and Never Will Be Another King Like Me,” helped set the tone for the endeavor, and to this day zany flamboyance and irreverent theatricality are characteristic of the club’s style, at least as far as its Carnival activities are concerned. Long before the likes of Snoop Dogg and Jay Z donned bling-bling and perfected the art of ostentatious bravado, Zulu Kings extolled their own greatness and flashed whatever finery they could muster to admiring multitudes.

The earliest Zulu members may have identified with the warrior sprit exhibited by the African Zulus in resisting colonialism, just as others in the black community who took up masking as Mardi Gras Indians identified with the defiance of Native Americans. Or they may simply have fancied the potential entertainment value of the African jungle theme, which served as a vehicle for transforming the image of the African Zulus as “noble savages” into a comic performance for public display.

According to the Zulu club’s official history, William Story reigned as the first Zulu king, in 1909. He wore a lard can as a crown and waved a banana stalk scepter. Subsequent Zulu kings were known to bestow blessings on royal subjects by wielding a ham bone. Having fun with the conventions and trappings of official (white) Carnival became part of Zulu’s trickster burlesque.

In a way, the Zulu parade brought back the “riotous quality” and “laugh and license” of pre-Civil War Carnival. Instead of orderliness and scripted decorum, it offered the uproarious spontaneity of the second line, whereby spectators, musicians, parade marchers and even float raiders would — to borrow a phrase from Louis Armstrong — “pitch a boogie-woogie.” (As a young man, Armstrong played his horn in the Zulu parade; he reigned as King Zulu in 1949.)

Baby Dolls and Bone Gangs

Members of the Treme Million Dollar Baby Dolls on Mardi Gras 2009

The original Baby Dolls constituted a permissive sisterhood that was determined to partake in the festivities on their own terms.

Among those in the thick of the Zulu second line were the Baby Dolls. Recalling the promiscuous maskers of the mid-19th century, who transformed the streets on Carnival Day into a bawdy free-for-all, this informal sisterhood sported frilly, titillating attire — typically, short skirts, bloomers, satin blouses and bonnets tied under their chins with ribbons. The first Baby Dolls appeared in the vicinity of the rough-and-tumble uptown red-light district, i.e., “Black Storyville,” around 1912. Baby Doll masking caught on, enabling women from various walks of life to publicly partake in transgressive flaunting or mocking of conventional expectations requiring them to suppress their sexuality.

The original Baby Dolls were anything but submissive. Male revelers looking to stuff money into the girls’ garters or stockings could receive a kick in the pants — or worse — if they got too out of line.

Also capitalizing on the freedom that Carnival represented for black and mixed-race celebrants were skull-and-bones gangs — a mysterious folk tradition in which maskers, in the guise of skeletons, bring the spirits of the dead to the streets. Donning oversized skull heads — primitive constructions sculpted from bale wire and cheesecloth, using papier-mâché techniques — they’d roam the Tremé neighborhood early on Mardi Gras morning, brandishing huge, bloody animal bones and raising a frightful ruckus. Serving a cautionary role, they’d warn children of scary comeuppances if they misbehaved. Amidst the frivolity of Carnival, these “Bone Gangs” or “Skeletons,” as they’re sometimes called, are macabre, “in-your-face” signifiers of transience and mortality. “You next” is one of the admonitions often seen emblazoned on their decorated aprons.

They’re also particularly apropos of New Orleans, a precarious place — haunted by a history of epidemics and vengeful hurricanes — where the living fervently memorialize and celebrate ancestral spirits through ritual and performance. It’s possible their origins derive from Haitian skeleton figures and the spiritual pantheon of voodoo. (Thousands of refugees from Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) arrived in New Orleans after the 1804 overthrow of the island nation’s French colonial government; most of them settled in the Tremé.)

A member of the Northside Skull and Bone Gang on Carnival Day 2011

While the history of these enigmatic maskers is sketchy, they have been rousing residents of the Tremé early on Carnival Day since at least the 1930s.

Mardi Gras Indians, Zulu, Baby Dolls and Bone Gangs comprised the key elements of “black Carnival,” which occupied its own realm apart from the official festivities. Its focal point was a verdant stretch of Claiborne Avenue running through the Tremé. There was much anguish when, in the 1960s, the majestic oak trees lining the street were felled so a freeway overpass could be constructed above the neutral ground, or median.

The history of New Orleans Carnival in the 20th century can be viewed as the story of broadening avenues of participation and a gradual blurring of boundaries once delineated by race, class and gender. The one constant is that individuals from every strata of society aspired to participate on their own terms. This led to like-minded cohorts joining together to form a host of new organizations that would adapt and reinterpret the conventional repertoire of local Carnival customs, while also introducing novel twists and practices.

The advent of “truck parades” brought working- and middle-class New Orleanians into the celebration on a participatory level. Rain forced the cancellation of the Rex parade in 1933, but as Reid Mitchell relates in his book All on a Mardi Gras Day: Episodes in the History of New Orleans Carnival, Chris Valley and fellow brothers in the Elks Lodge hit the streets with a truck float and five-piece band. When police refused them entry onto Canal Street — a space reserved for the blue-blood parades — Valley got the idea for assembling a brigade of truck floats — “motorized equivalents of the old promiscuous maskers,” as Reid describes them — as a way to build clout and gain access to the main thoroughfare of Mardi Gras. Since 1938, his Krewe of Elks Orleanians has followed the Rex parade.

No longer were regular folk confined to the role of sideline spectators, witnessing the processions of the exclusive krewes. Transforming a flatbed truck into a thematic float, and coming up with costumes and headpieces to accentuate the chosen theme, enabled whole families and friends of both sexes to engage in creative collaboration. “These mobile cabarets, complete with jazz bands and dancing, offered an alternative to formal, male-dominated parades,” notes Karen Trahan Leathem in her 1994 PhD dissertation, “ ‘A Carnival According to their own Desires’: Gender and Mardi Gras in New Orleans, 1870-1941.”

Stepping out: women reinvent their role

A Krewe of Muses float rider proffering a pair of “Chickendales” boxers

Masked women throwing underwear from floats — no one could possibly have imagined such a thing back when the first all-female parading krewe, Venus, took to the streets in 1941.

Around the turn of the century, it was generally assumed that only a woman notoriously lewd and abandoned would mask and dance in the street. But winning the right to vote, notes Atkins, “created an enlivened sense of public participation by women,” who, beginning in the 1920s, “engaged in Carnival behavior that was once acceptable only for men and prostitutes.”

The advent of all-female krewes spoke to women’s growing impatience with their ornamental roles in the traditional krewe balls orchestrated by men. In 1941, the Krewe of Venus, presenting the theme “Goddesses,” became the first all-female krewe to parade through the streets of New Orleans, “provoking a considerable amount of trepidation and even resentment from people who associated masked women with moral turpitude,” relates Anthony J. Stanonis in Creating the Big Easy: New Orleans and the Emergence of Modern Tourism 1918 – 1945. “Rain poured down, and some spectators throw tomatoes and eggs.”

The gradual democratization of Carnival, having gathered steam in the early decades of the 20th century, was in keeping with, if not motivated by, the “Every man a King” spirit of Louisiana politician Huey Long (who famously thumbed his nose at Mardi Gras by calling it a “silk stocking” affair for social blue bloods).

In the interwar years, businessmen and city officials worked assiduously to promote the city’s romantic antiquity and charm, while also shaping the image of Mardi Gras as a leisure attraction — as a way for tourists to “cast aside their everyday mores for a brief period of sensory indulgence,” writes Stanonis.

For Mardi Gras, boosters dressed up the city in celebratory garb and promoted costume contests, dancing contests and the closure of Canal Street to facilitate masking among revelers and tourists in proximity to downtown retail stores. Promotional campaigns spearheaded by the New Orleans Association of Commerce included hiring a film company to capture moving images of the festivities for national distribution to theaters and schools.

As a result of the boosters’ efforts, according to Stanonis, “the public image of Carnival as a time for the city’s elite to display their wealth and social standing became secondary to the public’s general enjoyment and participation in all aspects of the festival. Mardi Gras emerged as a national holiday celebrated in the unique setting of New Orleans.”

As the celebration became increasingly important to the city’s tourism industry, new krewes comprised of business and professional men, such as the Knights of Hermes and the Knights of Babylon, appeared. No longer was Carnival royalty born exclusively to the upper crust. In 1949, Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong, who played his horn in the Zulu parade as a young man, became Carnival’s first celebrity monarch, and fulfilled a boyhood dream, when he reigned as King Zulu. (“Man, this king stuff is fine,” he said. “Real fine.”)

Blaine Kern and post-war democratization

Blaine Kern with African Zulu warriors, and members of their entourage, at the 2006 Zulu parade

A pivotal force in opening up participation in Mardi Gras, shaping the look parades and recruiting big-name celebrities to ride, he traveled to South Africa to woo African Zulus to come to Mardi Gras as a gift to the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, whose members were particularly hard hit by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

But alas, the years following World War II, during which festivities were canceled, saw only dim traces of the virtuosity and panache that had characterized the Golden Age. Floats had become predictable and somewhat drab, typically resembling large, gussied-up baby carriages. Then along came a young artist named Blaine Kern, whose father, Roy, had built floats for the krewe of Alla in the 1930s.

In 1947, at age 20, Kern, after a stint in the Army, founded Blaine Kern Artists. Within two years, he had the contract to build the Rex parade.

In the early 1950s, the then-captain of Rex, Darwin Fenner (whose father was the Fenner in Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith), dispatched Kern to Europe to study Carnival traditions in Cologne, Nice, Frankfurt, Viareggio and Valencia. The floats that upstart Kern subsequently introduced to the streets of the Crescent City were fanciful, if not outlandish: decked out with oversized, vividly colored busts of storybook creatures and characters whose heads turned and whose eyes moved.

A pivotal force in opening up participation in Mardi Gras, shaping the look parades and recruiting big-name celebrities to ride, he traveled to South Africa to woo African Zulus to come to Mardi Gras as a gift to the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, whose members were particularly hard hit by Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Kern would become the city’s dominant float builder and a key player in fostering the formation of new krewes. Many new clubs would hit the streets as parading became more affordable, after Kern began building floats and buying tractors to rent out to others. The floats had detachable features so they could be adapted easily to any number of themes. As Carnival became a less exclusive affair, its economic impact on New Orleans multiplied.

Indeed, thanks in no small part to Kern, a k a Mr. Mardi Gras, what was once essentially a seasonal ritual for locals would witness a huge expansion in the annual number or parades, media coverage and tourist interest. Consequently, as sociologist Gotham has observed, the Mardi Gras “experience” became more accessible to outsiders and, in the process, increasingly associated with mass entertainment and consumer culture.

Sequins, feathers and gay civil rights

Original members of the Krewe of Yuga at their third ball, in 1961

The license provided by Mardi Gras for acting out fantasies and transgressing social boundaries nurtured a gay ball subculture and helped make New Orleans a gay mecca.

— Photo courtesy of First Run Features

The traditions of gay Mardi Gras officially began with the Krewe of Yuga’s first Mardi Gras drag ball, in February 1958. In 1962, the event was held at a rented school cafeteria in conservative Jefferson Parish — and raided by the police.

As Tim Wolff recounts in a synopsis of his feature documentary The Sons of Tennessee Williams, which tells the story of the New Orleans men who worked with the traditions of Mardi Gras to bring gay culture into public settings long before the start of the gay civil rights movement: “Krewe members attempted to escape by running into the swamplands adjacent to the school, chased by officers with dogs and flashlights. Many were betrayed by their glittering costumes while hiding in the dark night and tall grasses of Jefferson Parish.” Ninety-six men were taken to jail, booked for “disturbing the peace” and identified by name in the newspaper, which described the event as a “stag party.”

In 1964, Arthur Jacobs, an ex-police officer looking to drum up some business for his French Quarter restaurant, Clover Grill, started a Mardi Gras costume contest called The Bourbon Street Awards. Thanks in part to its proximity to Cafe Lafitte in Exile, a popular gay bar, the event — billed as “The Greatest Free Show at Mardi Gras — would become a magnet for drag queens and over-the-top costumes made for gay balls.

By 1969, four gay Krewes were legally chartered by the state of Louisiana as official Mardi Gras organizations, holding annual pageants at public venues across the city. Hundreds of people attended the balls, including straight female friends of krewe members. Wolff’s documentary makes the case that New Orleans was the first place in America where gay and straight people came together to publicly recognize gay culture, years before the start of gay pride marches commemorating the June 1969 police raid on the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village — an event widely credited as the catalyst that brought gay people out of hiding.

Gay balls thrived into the 1980s, as a slew of new krewes built on New Orleans’ already formidable reputation for extravagant artistry. And although the onslaught of AIDS and the devastation of Hurricane Katrina took a heavy toll on the local gay community, the remaining krewes — among them Amon-Ra, Lords of Leather, Petronius, Armeinieus and Satyricon — continue a tradition of elaborately produced balls staged before a seated audience. Costumed krewe members typically appear in scripted tableaux based on a theme, and the overall effect is usually humorous, if not outlandish.

While the official Carnival parade schedule would see plenty of changes as new krewes came and went, the old-line parades remained the featured attraction of the gala through the 1960s. The prerogatives of the elite krewes, in fact, extended well beyond the festivities. The Carnival aristocracy, as J. Mark Souther notes in his book New Orleans on Parade: Tourism and the Transformation of the Crescent City, “not only planned lavish social events but also exercised overwhelming influence on the city’s economic direction and its politics.”

The “superkrewe” razzamatazz of Bacchus

Krewe of Bacchus Bacchatality float, so named because it carries members who work in the hospitality industry

A flashy — and hugely popular — extravaganza from the get-go, Bacchus signaled a cultural shift away from the longstanding dominance of the old-line krewes and toward the production of spectacles associated with mass entertainment.

In the late 1960s, entrepreneurs and others lacking blue-blood pedigrees came together in an effort to promote tourism and broaden the avenues of participation in Carnival. They formed the krewes of Endymion, in 1967, and Bacchus, in 1968. You needed no social credentials to join. And instead of ceremonious balls featuring krewe royalty, these so-called “superkrewes” threw raucous “extravaganzas” with big-name entertainment. Further departing from tradition, their parades boasted celebrity riders and huge, double-decker floats. And their unprecedented generosity with throws abetted the appetite of the cheering throngs and made the older krewes seem almost stingy by comparison.

The first Bacchus parade in 1969 — which featured Danny Kaye, a Jewish actor from Beverly Hills, as its monarch — signaled a cultural shift away from the longstanding dominance of the old-line krewes and toward the production of razzle-dazzle spectacles depicting fun, accessible themes. Bacchus and krewes that followed its example, most notably Endymion and Orpheus, energized participation in Carnival and significantly enhanced the celebration’s stature as a tourist attraction. Today, their Kern-built floats — with elaborate sound systems, fiber-optic lighting and other special effects — set the standard for over-the-top extravagance and high-tech innovation.

Reveling on the fringes: Carnival counterculture

Reflecting broader social currents of youth questioning authority and conventional expectations of the “Establishment,” many New Orleanians who came of age in the 1960s and ’70s found themselves drawn toward freewheeling modes of expression that, in the realm of Carnival, improvised on the old traditions. Rejecting the prefab culture and rational orderliness extolled by modern society, subterranean tribes such as the Society of St. Anne, Krewe of Kosmic Debris, Mystic Orphans and Misfits (MOMs) and the Krewe of Dreux exhibited a loose, impromptu style — indulging in primal fantasies and reveling in the possibilities of the moment.

Box of Wine rolling on St. Charles Avenue in 2008

A gonzo affair that strives to recreate the communal ecstasy of ancient Dionysian rites in which wine was a medium of religious experience, Box of Wine has become an idiosyncratic centerpiece of Carnival counterculture.

With the exception of MOMs, whose raison d’être is a raucous costume ball, these groups represented the evolution of a tradition — of footloose marching or walking clubs — dating back to the 1800s. Venerable practitioners such as the Jefferson City Buzzards, founded in 1890, and Pete Fountain’s Half-Fast Walking Club still take to the main parade route along St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street on Carnival Day. And, in a testament to Carnival’s capacity to accommodate upstarts, even decidedly offbeat ensembles like Box of Wine and the Mondo Kayo Social and Marching Club have managed obtain permission from the city to raise a ruckus before the assembled throngs on the official parade route (the former on Bacchus Sunday, the latter on Fat Tuesday). Still many others are content to revel around the fringes — rambling with abandon through the French Quarter and neighborhoods off the main thoroughfare.

The most influential alternative Carnival organization to emerge in the latter part of the 20th century was the Krewe of Clones. Its masterminded was Denise Doughtry, who, for her Tulane University M.F.A. thesis in 1971, staged a musical, science fiction-themed Mardi Gras ball as a performance art event. Among those in attendance was Don Marshall, who would go on to become the first director of the Contemporary Arts Center, a converted four-story, red-brick warehouse on Camp Street, in midst of what was then skid row. Founded in 1976, the CAC quickly become a vibrant creative hub — combining exhibition and performance space, for artists working in a wide spectrum of disciplines, with a generous helping of social hoopla. Marshall asked Daughtry to create a fundraising event for the CAC along the lines of her M.F.A. production.

Organized under the auspices of the CAC, the Clones first paraded in what is now known as the Warehouse Arts District in 1979. Their theme: Songs and Stories of the National Enquirer.

A wild and wacky Mardi Gras arts collective, the Clones represented a break from the packaged modus operandi of “mainstream” parades. “Packaged” in the sense that the experience of a typical member of a mainstream krewe is fairly effortless: you pay your dues and basically just show up for the parade and parties. Float decoration services, masks, costumes and mass-produced throws are procured from outside suppliers.

By contrast, Clones had a hands-on, do-it-yourself ethos. With everyone pitching in to design and build the parade from scratch, participants were highly invested in the endeavor, with creative ownership of costumes, signs, thematic interpretations, performances and constructions. Various groups, each comprising a “unit” or “subkrewe” in the parade, had considerable autonomy in deciding how to interpret the overall theme. Members, in turn, could develop and depict individual fantasies within the context of their subkrewe’s presentation.

The Clones, marching in the name of art, united the arts community and creatively inclined fun-seekers in a single, multidisciplinary street procession, synthesizing a wide array of performance and visual arts traditions. The themes, most famously 1984’s Celebrity Tragedy, seemed to encourage artist-revelers to flaunt decorum. And with the vast majority of Clones maskers parading on foot, there was an electrifying intimacy with spectators — an extemporaneous give-and-take not dependent on throws. The result was a rollicking circus of a parade with an off-the-wall, Saturday Night Live sensibility.

The Clones recalled the early days of Carnival, of informal walking parades and social lampooning. “Originally Mardi Gras was a trashy street parade with a bunch of lunatics like us,” Daughtry, in an interview with Times-Picayune columnist Angus Lind, once explained. “But somewhere it got lost along the way. Originally Carnival satirized society. Now Carnival has become society.”

2011 Krewe of CRUDE float lampooning the BP oil spill debacle in the Gulf of Mexico

After the implosion of the Clones in 1986, CRUDE was one of four subkrewes that regrouped to partake in the Krewe du Vieux, which continued the renegade ways of the Clones.

— Photo by Pat Jolly

Although the Clones were a big hit with the public, garnered national publicity and proved to be a potent fundraising vehicle for the CAC, tensions over the krewe’s image mounted as the arts center evolved from being an experimental oasis — which flew by the seat of its pants and readily indulged the rule-bucking whims of young local artists — into a polished jewel in the crown of the city’s cultural establishment. Some members of the CAC’s board of directors felt scandalized by the parade’s outré shenanigans, which included marchers got up as hemorrhoids and depictions such as “Hollywood Habits: The Drugs of the Stars,” in which members the Krewe of CRUDE (Council for the Revival of Urban Decadence and Entertainment) costumed as different drugs (one was a gigantic nose with rolled-up hundred dollar bills protruding from its nostrils, following a trail of white power tossed onto the street).

In 1986, Super Bowl XX was scheduled to take place at the New Orleans Superdome the day after the Clones parade. Rebellion was in the air as some of the subkrewes balked at efforts by the mother krewe’s brain trust to raise dues and impose guidelines. As it turned out, then-mayor Ernest N. Morial personally intervened to have the parade permit revoked. “He called me ‘a public endangerment to the image of the city of New Orleans,’ ” Daughtry would later recall in an interview with MardiGasUnmasked.com.

In a defiant demonstration of Mardi Gras spirit, some Clones joined up for a ramble through the French Quarter on the night before the Super Bowl, while others staged a “Death of the Clones” funeral march in Mid-City. Daughtry subsequently fell out with CAC and — along with artist, musician and bon vivant George Schmidt — wound up developing a new Carnival endeavor, the Avant Garde Club. A tony affair with relatively high membership dues, centralized creative control and tastefully rendered, small-scale floats, it was a conscious departure from the renegade ways of its predecessor. The krewe paraded for two years, and although considered an artistic and intellectual success, it lacked the vitality of spirit that had animated the creative anarchy of the Clones.

Krewe du Vieux rises from the ashes

Don Marshall and Lolet Boutté reigning over the Krewe du Vieux’s 25th anniversary parade in 2011

With a knack for nurturing the talents of rule-bucking young artists and instigating multidisciplinary collaboration, the former director of the Contemporary Arts Center was a key player in the formation of both the Clones and the Krewe du Vieux.

— Photo by Pat Jolly

Enter, once again, instigator Marshall, who had left the CAC to run the historic Le Petit Theatre du Vieux Carré. At his urging, four of the Clones subkrewes, plus additional recruits, reconstituted for Mardi Gras 1987 under a new umbrella called the Krewe du Vieux Carré (translation: Krewe of the Old Square, i.e., French Quarter). They managed to finagle a permit to parade through the Quarter before the start of the “official” Carnival parade season.

The krewe barely made it through some lean years in the early 1990s, when it had to advertise to recruit members. Some of the subkrewe efforts were slapdash, and attempts at float construction more the exception than the rule. But the diehard members had a profound belief in the wisdom of fools and the invisible guiding hand of the Muses — the guardian angels of the creative spirit — as well as a missionary zeal for facilitating communal catharsis through the merciless ridicule of dubious public figures. (In terms of risqué and politically incorrect, completely uncensored content, the Krewe du Vieux, as it is commonly known, has far surpassed the Clones.)