In New Orleans, the indoctrination of children into the accoutrements and rituals of Mardi Gras — costume closets, king cake parties, watching parades from atop festively festooned ladders and wielding butterfly nets to snag airborne trinkets — begins practically at infancy.

Members of the Young Guardians of the Flame, whose identity is rooted in Native American and African traditions, on Carnival Day 2011

In New Orleans, children learn from an early age that making wearable regalia for Mardi Gras is an art form unto itself.

With the culture of merriment and make-believe woven deep into the city’s cultural and social fabric, people from all walks of life cherish children’s Mardi Gras traditions and accoutrements including photos and memories of being dressed up in costumes lovingly sewn by their mothers. And something about the archetypical sounds and sights of the parades – the rhythmic excitement of marching bands, the vividly colored storybook floats and the mysterious riders showering beads and baubles into the outstretched arms of cheering throngs – stirs young imaginations and sinks deep into the psyche. So much so that even in one’s advancing years, long after the childhood thrill of Christmas morning has faded, the mere sound a drum roll heralding the approach of a parade can bring tingles of anticipation and, if only for a fleeting moment, summon the lost innocence of youth.

If all the throws, eye candy, fun and excitement weren’t enough to induce allegiance to the festivities, moreover, there’s the fact that the children of the realm are freed from their studies – not just on Mardi Gras, but for the better part of a week.

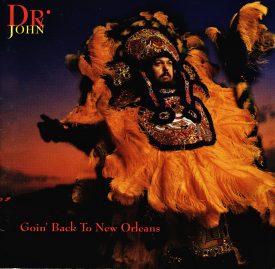

The cover of Dr. John’s Goin’ Back to New Orleans

The Grammy Award-winning album includes an uptempo version of the traditional Mardi Gras Indian song “Indian Red,” with shout-outs to Big Chiefs of legendary tribes renowned for their aesthetic and musical contributions to New Orleans and Mardi Gras.

If there’s an occasional downside, it’s one to which children the world over can relate: parents with all sorts of fancy ideas about using a festive occasion to show off offspring to their supposed best advantage. In his memoir Under a Hoodoo Moon: The Life of Dr. John the Night Tripper (St. Martin’s Press), Mac Rebennack recalled that although his mother was “cool” she was always “pushing me to be with society-type people. One year she finagled to get me into a kids’ Mardi Gras ball. She did me up a costume, a little prince’s outfit or some such thing: I was getting into the get-up, but when she hit me with a wig I freaked. I hollered, threw the wig across the room and refused to wear it; she had to do a lot of calming me down before I let her put it back on.”

But mama, who had a business making hoop skirts for girls and women who attended Carnival balls, would seem to have triumphed in the long run. In fashioning his conjureman Dr. John persona in the late 1960s, Rebennack took to wearing elaborate hoodoo regalia — headdresses and plumes, and necklaces of bones and beads.

“One woman, Sadie Hayes, made me a suit of alligator, snake and lizard skin with chamois in between to hook it all up.,” he recalls in his book. “When I put on that uniform, I looked like Frankenstein coming down the street. When this stuff started coming apart in pieces, I had to start hanging around taxidermy shops big time, scavenging new material to help put things back together.”

And on the cover of his Grammy-winning 1992 album Goin’ Back to New Orleans, the originator of the anthem “Mardi Gras Day” is resplendently attired in a Mardi Gras Indian suit.

Once a masker, always a masker.

MardiGrasTraditions.com