Make way for The (Grocery Cart) Queen of Mardi Gras! Over the years in the City that Care Forgot, the uproarious adventures of Krewe of Coleen have yielded countless Kodak Moments. In 1998, after a three-year hiatus, Queen Coleen—children’s literature guru, professional raconteur and consummate New Orleans eccentric—returned to her rolling throne to stave off boredom and enrich the panorama of Mardi Gras. But this beloved character’s experience and talents extend well beyond “just foolishness.”

The (Grocery Cart) Queen of Mardi Gras

Queen Coleen in her French Quarter courtyard, with royal accoutrements

The gilded replica of the Royal Chariot—on the rack underneath the basket is a box labeled “Dixie,” as in the beer—was a gift from an old Mardi Gras cohort, Reva Stover, who also crafted Her Highness’ purple velvet crown.

“This was way back at the beginning.”

Coleen Salley (a.k.a. Queen Coleen) is showing a visitor to her French Quarter apartment a published collection of Mardi Gras photographs by Harvey Glick. On the cover is a photo from her early years of parading, in the mid-to-late 1970s. She’s captured in her rolling throne—a grocery cart—in all her glory. Donning a purple velvet crown and reveling in the devil-may-care hilarity of the moment, her head tossed back and a can of beer in hand, she looks as if she were cackling at the gods above.

Settling in, Queen Coleen—children’s literature guru, professional raconteur and consummate New Orleans eccentric—proceeds to relate the story behind the photo.

Initially, she was mystified by the presence of two guys in funny hats who stood beside the cart gazing at her. “And one of my sons [David] said, ‘Oh, mama. I know who that was. That’s when we were all dancing to a band, and we had parked you over on the curb. And we were dancin’, and all of a sudden we looked up and those guys were going off down the street with you. And you were drinking beer, and didn’t know who was pushing the cart.’ He said, ‘They cart-napped you.’ ”

Closer inspection revealed that the shot had been taken just after members of her krewe had to come running to the rescue. Queen Coleen (pronounced CO-leen) points to a couple of faces partly cut off along one edge of the photo. “This is Jeff Howell’s profile,” she says, indicating one nose, “and this is Evans Howell.” The brothers were “arguing [with the cart-nappers] about to whom I belonged. And,” she continues, “I’m there drinkin’ beer, and don’t care, obviously.”

Over the years in The City That Care Forgot, the uproarious adventures of Queen Coleen have yielded countless Kodak Moments. Indeed, her renown as an exceptionally colorful character is such that she was among 70 people, both famous and unknown, tapped to partake in a project organized under the auspices of The International Center of Photography, in New York City. Among the celebrity participants were Rosa Parks, Benjamin Spock, Ginger Rogers, Martha Stewart and John Updike.

Each person submitted a single photograph—it didn’t necessarily have to be of themselves—along with an essay explaining its personal significance. The exhibit, entitled “Talking Pictures,” opened in New York City in the fall of 1994, then traveled throughout the country. Alongside each photo was a handset; by picking it up and pressing a button, you could hear a recording of the person discussing the photo they’d selected. Queen Coleen submitted a group shot taken by a local photographer, Linwood Albarado Jr., a decade or so after the Harvey Glick photograph. It portrays the Krewe of triumphantly rolling their namesake monarch down the street on Fat Tuesday 1988, spreading good cheer.

The project also included a book, entitled Talking Pictures: People Speak Out About the Photographs that Speak to Them (Chronicle Books, 1994), in which Queen Coleen explains how her procession emerged, circa 1974, out of a closely knit group consisting of herself and her kids and their friends.

Queen Coleen’s “Talking Pictures” submission

Reveling in her Royal Chariot, she became one of the most photographed subjects in the history of Mardi Gras.

“That year it was late, and I was getting tired of standing at the parade, even though I was much younger and less heavy than I am now. A kid came by with a grocery cart. I looked at it and said, ‘Oh God, I wish I had that to sit in.’ And the little boy said, ‘You want it lady?’ ‘Yeah, darlin’, I do.’ So I called to my krewe, ‘Help put me into this thing.’

“All of a sudden, this wonderful jazz band came marching through the crowds. I said, ‘Oh my God, let’s go with that band! Just push the damn grocery cart.’ And then one of my girls, she started calling out, ‘Make way for the Queen of Mardi Gras!’ And honey, it was like Moses and the Red Sea. ‘Here comes the Queen! Here comes the Queen.’ And the next thing you know the band is following us, and I’m sitting in a grocery cart in just regular old street dress, no costume.

“Everybody thought the Queen had to have a beer or a drink out of their wine bag, and the Queen got so drunk sitting in the grocery cart that the kids ended up taking care of me. I thought, ‘I like this.’ Instead of me worrying, ‘Where are the kids?’ they have got to take care of me. So the next year I just started off in the grocery cart. That way they couldn’t desert me, and they could always find me.”

Thus was The (Grocery Cart) Queen of Mardi Gras enthroned.

Ever since, shutterbugs have been drawn to Krewe of Coleen like moths to a porch light on a summer night. “There must be a million copies of this kind of picture around the United States,” wrote Queen Coleen, referring to her “Talking Pictures” submission, “because the parade is so tacky that everyone who sees it wants a picture….Now I’ve got a cult following.”

That Queen Coleen, a woman of some heft, can even fit into a grocery cart is no small feat. For years, sitting in the cart with her legs doubled back under her butt, she endured no small amount of stress on her knees. But after she underwent foot surgery, necessity became the mother of invention: Krewe members took a pair of heavy-duty wire clippers to the cart, cutting an opening so that Queen Coleen could sit with her legs extending through the bottom of the basket.

Yet even after this modification, with Queen Coleen’s lower body obscured by crepe paper and other decorations adorning the so-called Royal Chariot, some people would mistake her for an invalid. For them, recalls Jeff Howell, the beer-swilling grocery-cart lady was a source of inspiration. Among the comments he remembers overhearing: “Aw, she’s so brave. She’s just as happy as she could be, and she ain’t got no legs.”

Through the years there certainly have been many memorable episodes, like the time when Queen Coleen and her gang were out on Canal Street and somehow found themselves caught between floats in the Rex parade. “You know, when you’re standing there it doesn’t look like the floats are goin’ that fast,” she says. “But when you’re in front of one? I mean to tell you, we were hot-footin’ it, with my band and my krewe…pushin’ the cart as fast as they could.” The police saw what was going on and motioned for the revelers to make an exit through a gap in the barricades lining the street—which they promptly did.

“I thought, ‘Oh, well. This is it; they’re going to get the paddy wagon and drag us out,’ ” drawls Queen Coleen. But the officers, perhaps amused by the improbable spectacle, let the krewe go on their merry way.

Mother, school teacher and life of the party

Thanks to her Royal Chariot, Queen Coleen is, to be sure, one of Mardi Gras’ most recognizable characters. But people who know her as a mother and school teacher have often been taken aback by her royal escapades. “One of the most fun things,” relates krewe veteran Jean Howell, “was just going through the crowd and hearing people say, ‘Miss Salley, is that you in that grocery cart?’ I mean, they would be shocked, and they’d turn to their friends and go, ‘That’s my teacher; she’s in that grocery cart!’ Or friends of her children would go, ‘Oh, my God! Is that George’s mother in that grocery cart?’ ” (George Salley, who now lives in San Diego, is the eldest of her three children.)

Queen Coleen is a native of Baton Rouge, La. Her husband, Elmore, died in a car crash when she was 31 years old, and she never remarried.

For the Howell family, also of Baton Rouge, Queen Coleen and her family were practically next of kin. Jean Howell and her three younger brothers were roughly the same age as Queen Coleen’s brood. As a widow, Queen Coleen often found herself partaking in revels involving her children and their friends.

Relocating to New Orleans in 1964, she eventually bought a house near the shore of Lake Pontchartrain. During Mardi Gras, it became party central. “The informality of my home lent itself to kids coming in and throwing their sleeping bags on the floor,” says Queen Coleen, reflecting back on the origins of the Krewe of Coleen.

Jean Howell “really got this show on the road way back in the beginning,” relates Queen Coleen. But the krewe truly came into its own when the Howell boys—first Evans, then Jeff, then Phil—began joining in. Their penchant for chants, acrobatic dance moves and madcap antics, like drinking beer from a shoe, infused the whole endeavor with a rowdy esprit de corps. “The Howells come from a long line of people who are very comfortable making an ass out of themselves…,” notes Evans. “It comes in very, very handy at times like Mardi Gras.”

In 1985, Jeff, then pursuing a career as a professional musician in Orlando, Fl., began introducing some of his musical friends to Mardi Gras. Accompanied by a band, the Krewe of Coleen cut a wider swath. “You have got to make some noise,” declares Queen Coleen; “you can’t just stand there with somebody hollerin’, ‘Make way for the Queen!’ You’ve got to draw the attention of the crowd so they’ll let you through.”

Further enhancing the krewe’s reputation for attention-grabbing routines and gimmicks: colinder hats, known as “CO-leenders.”

The tradition got started back in the early 1980s. While working as an entertainer for Showbiz Pizza in Orlando, Jeff, as promotional stunt, came up with the idea of having employees and patrons partake in “colinder-head” parties. As he recalls, “everybody would wear a spaghetti strainer on their head, and they would decorate it in their own personal way.”

Donning a “Coleender”

Krewe members came up with their own individual takes on this madcap tradition.

Not surprisingly, given its affinity for tomfoolery, the Krewe of Coleen readily embraced the craze. And though it only lasted a couple of years, some members are still partial to their Coleenders.

As Krewe of Coleen rolled into the 1990s, certain key devotees could no longer make the gig, as they lived out of state and now had families to raise, among other obligations. As a result, with the krewe’s energy level waning, Queen Coleen got to thinking about retiring.

In the fall of 1993, she moved from her house near the lake to new digs on Chartres Street in the French Quarter. Having had her furniture recovered, the last thing she wanted was bunch of drunks making a mess of the place.

A special brand of foolishness

Mardi Gras 1994 was to be the Queen’s farewell parade. Commemorative T-shirts were printed up for the occasion, and a great time was had by all. That night, a core group gathered at Queen Coleen’s apartment to eat, drink and reminisce about the day’s events. Someone floated the idea of having a full-on Krewe of Coleen reunion parade for Mardi Gras 2000. “So I said, ‘Well, okay—if I’m still alive,’ ” Queen Coleen recalls.

For Mardi Gras 1997, Queen Coleen—who’d skipped town during the festivities the two previous years—was looking forward to sharing food and drinks with friends at her apartment and then heading out to catch some of the action in the Quarter. All those years of having been stuck a grocery basket, with her field of vision restricted, had left her thinking that she’d missed out on the full panorama of Mardi Gras—deprived, as it were, of the main course in the visual feast. Being a spectator would make for a nice change, she figured.

She hit the streets with a dear friend and longtime krewe member from Baton Rouge, Sue Turner. According to Queen Coleen, Turner is a “fastidious” Southern Lady whose attraction to Mardi Gras and its attendant debauchery is a source of amazement to those who know her. “She evidently has a wild hair up her ass if she finds this fun.”

Cruising the Quarter, “I had some people come up and say, ‘Oh, Queen Coleen! Are you going to parade again? We missed you.’ And I said, ‘No, dear. I’m just, you know, part of the crowd. Not going to parade anymore.’ ”

After a while, the duo found themselves back at the apartment, cooling their heels and watching as people walked by outside. But something about this “adult” Mardi Gras, without Queen Coleen’s royal subjects around to wreak havoc, seemed lacking.

It wasn’t long before Her Highness grew restless. Outside, the human circus beckoned. Might as well hit the streets.

“I mean, I’m runnin’ out of years,” says Queen Coleen, “and I don’t allow myself to be bored….I don’t want people boring me, I don’t want things that are boring. What if I spent an hour with a bore, then I got out on the street and someone runs me down? That was my last hour on earth, and I spent it being bored? Hell no, not me.”

Taking in the scene with granddaughter Catherine Salley and Sue Turner

By the turn of the millennium, the krewe had become a multi-generational affair.

Venturing out again, Turner and Queen Coleen, who were hoping to observe divine costumes, instead happened upon an appalling scene. “There was some spaced-out asshole…,” Queen Coleen recounts, “and he was being encouraged by the onlookers. And he was playin’ with himself and pullin’ his wang-doodle, and it was so disgusting….And I go, ‘Well, shit; that isn’t funny to me.’ So we wandered away from there, and finally I said to Sue: ‘God damn. All these years I thought I was missing something. I wasn’t missing anything.’ ”

Memories came flashing back. Memories of random people from years past whom she’d seen sitting on some stoop, looking forlorn or worn out, or maybe just lost in their own world. “And we’d come by and…my krewe would holler, ‘Hail to the Queen!’ And they’d look up and here was this old woman in a grocery basket, and a smile would break out on their face…. Momentarily, there was that absolute delight with this foolishness,” says Queen Coleen. “So I told Sue: ‘You know, we really were adding another dimension to Mardi Gras, just another fun memory for someone to take away.’ ”

Indeed, Queen Coleen hadn’t been missing anything after all; “but,” she says, “I had to find out for myself.”

That night she phoned her son David, who’d bought her old house by the lake. After the farewell parade in 1994, she’d told him to get rid of the old grocery cart. Was it still there? “He said, ‘Oh, yeah. I’ve been meaning to throw that thing away.’ I said, ‘Don’t throw it away! We’re going to roll next year.’ ”

And roll they did. It was a small but energetic group, beatin’ on drums and hollerin’, with Jeff Howell throwing down some fancy gymnastic moves—a style of dancing known as Poppin’ the Gator. “It really was wonderful fun,” says Queen Coleen. A number of people were surprised to see Krewe of Coleen back in action and “just made a great to-do over us; we felt real good.”

Saying “to hell with the slip covers,” Queen Coleen even wound up playing host to krewe members from out of town. “They brought their sleeping bags and inflatable mattresses,” she reports, “and junked-up my apartment royally….The very thing I dreaded came to pass.”

A “character” in life and art

A beloved character in the world of Mardi Gras, Queen Coleen also is a legend in the world of children’s books. After a 30-year career at the University of New Orleans, she retired in 1994 as Distinguished Professor of Children’s Literature. She has since authored five children’s books including an acclaimed series about an endearing Louisiana possum, Epossumondas (the first installment was herarled as a “treasure“ in the New York Times Book Review). His human “mama,” in both her appearance and in her folksy, sharp-tongued manner of speaking, is a Queen Coleen doppelgänger.

Besides a blossoming second career as an author, Queen Coleen promotes reading through storytelling, previews children’s books for teachers and librarians, conducts workshops and makes professional presentations at conferences. In 2004, she launched the Coleen Salley-Bill Morris Literacy Foundation. Also a legend in the field, Morris, who passed away in 2003, worked at the publisher now known as HarperCollins Children’s Books for 50 years. The foundation promotes literacy in under-served K through 8 schools, with an emphasis on providing children with the personal experience of connecting with authors and artists of children’s books.

Writing in the New Orleans Times-Picayune in November 1997, Marigny Dupuy noted that Queen Coleen is “a friend to the famous and a fairy godmother to the beginners, from authors and illustrators, to editors, publicists and sales reps in most of the major publishing houses—she knows them all. And they ALL know her.”

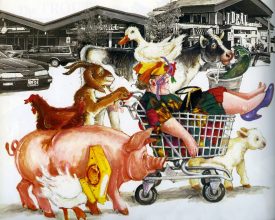

The impetus for the article was Queen Coleen’s starring role in To Market, To Market (Harcourt Brace & Company, 1997), written by Anne Miranda and illustrated by Janet Stevens. It was Stevens’s idea to model the book’s main character—a shopper who goes to the market “to get a fat pig”—after Queen Coleen.

Janet Stevens illustration from To Market, To Market (©1997 Harcourt Brace & Company)

On Mardi Gras, Queen Coleen gets carted around by a bunch of party animals.

Going back and forth from the market to her kitchen, the shopper carts home a bunch of unruly animals. They run amuck, causing her to become increasingly exasperated and disheveled (“There’s a duck on my head!”). Eventually, she gets the animals to push her back to the store in the grocery cart, and buys vegetables to fix a delicious soup.

Stevens, who also illustrated the Epossumondas series, has known Coleen Salley the storyteller and children’s literature expert for years. Asked if her friend’s penchant for being carted around on Mardi Gras by a bunch of party animals had anything to do with her becoming a model for the character in the book, Stevens says: “I think I did know she rode in Mardi Gras, and it helped in my decision to use her or somehow, in my mind, influenced the idea.”

On the book’s cover, the shopper is shown in profile wearing a yellow hat, on top of which is perched a large white duck. Queen Coleen would up using the illustration for the cover of a slick brochure, promoting her services as a raconteur. “Coleen Salley: Storyteller Extraordinaire,” the brochure proclaims.

In a section called “Lagniappe! A Little Sumpin’ Extra,” she’s described as “a multi-talented entertainer who has charmed people outside the book world, too, delivering banquet speeches and amusing talks laced with her own peppery brand of Louisiana folk humor….”

“With the adults,” explains Queen Coleen in an interview, “I do more salacious kinds of things.”

In fact, her experience and talents go beyond the written word and the oral tradition. Another of her personae is that of “Christmas freak.” For Christmas 1998, her apartment boasted three seven-foot trees, a six-footer and a 10-footer, not to mention an assortment of creches and tabletop trees. About 600 people, on a tour of festively decorated French Quarter residences, visited the apartment .

Deadpans Queen Coleen, with considerable understatement: “I do something besides just [Mardi Gras] foolishness.”

MardiGrasTraditions.com