What many people would regard as junk is, for New Orleans artist John Lawson, a “natural resource”—and a compelling artistic medium. A native of Birmingham, England, he uses Mardi Gras beads to bedeck all manner of objects–pianos, bongo drums, shoes, bones, mannequins, skulls, even antique bathroom scales–with intricate, visually intoxicating tableaux. It all began with a hallucinogenic Mardi Gras trip in 1984.

The Hieronymus Bosch of Beads

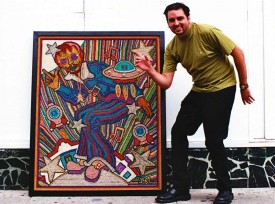

John Lawson in his studio at the Audubon Hotel

His intoxicating tableaux testify to the potential of an indigenous resource–Mardi Gras beads–as an artistic medium.

After the last parade rolls down St. Charles Avenue on Fat Tuesday, and before the sanitation crews and mechanized street sweepers begin the massive job of clearing the detritus of the festivities, New Orleans artist John Lawson swings into action—scrounging the street and neutral ground, as the grassy medians that divide the city’s avenues are known, for beads and trinkets. In video footage shot by his girlfriend, Elizabeth Morgan, the night of Fat Tuesday 1999, he could almost be mistaken for one of the Orleans Parish prison inmates who volunteer for Mardi Gras cleanup duty. He’s dressed drably in heavy clothes, with a wool cap pulled down over his face and double-lined Hefty garbage bags tucked into his belt. Commenting on the video, Lawson says he likes to remain “as inconspicuous as possible.”

“It’s kind of eerie that time of night,” he points out, noting the presence of a small horde of people hell-bent on “scavenging” for recyclable containers and “throws”—beads and other items tossed by masked riders on parade floats—as well as furniture and picnic accessories abandoned by parade-goers.

Lawson, who spends hours methodically filling his bags with booty, likens himself to “a hound” and says, “It reminds me of raking blueberries in Maine.”

He certainly reaped a bountiful harvest in 1999: five bags full of throws, mostly beaded necklaces. Indeed, what many people would regard as junk is, for him, a “natural resource”—and a compelling artistic medium. He uses Mardi Gras beads to bedeck all manner of objects—pianos, bongo drums, shoes, bones, mannequins, skulls, even antique bathroom scales—with intricate, visually intoxicating tableaux.

Prime example: a striking series of flat panels installed along the Audubon Hotel’s bar top. The imagery is as detailed as it is varied. Mixed in with aquatic scenes and various motifs inspired by Hieronymus Bosch’s otherworldly triptych Garden of Delights, is Lawson’s depiction of a female drag queen named Myra (along with other colorful, real-world denizens of the Audubon’s notoriously randy bar scene) and a yellow Teletubby—Lah Lah, from the cult children’s TV show.

Lawson’s Garden of Delights bar top commissioned for the Audubon Hotel

The two ears impaled by an arrow and flanking a knife blade is one of several images transposed from Bosch’s painting.

Jonn Spradlin commissioned the 54-foot-long labor of love, which took Lawson three-and-a-half months to complete. In 1996, Spradlin, along with his friend Clinton Peltier, purchased the hotel, then a seedy redoubt for merchant seamen, and proceeded to transform it into a haven for inspired kinkiness and artistic mayhem. Lawson found himself in the thick of it, residing at the hotel and keeping a watchful eye out for the establishment’s oddball assortment of dwellers and patrons.

The bar top, coated with clear polyurethane resin, includes portraits of Peltier, who passed away in 1998, and Murphy “Mouse” Adams, a retired merchant seaman who frequented the bar nearly every day for 30 years (he passed away in 1999). Among the various aquatic creatures depicted is a blue octopus—a nod to Spradlin’s wife, Peggy, who likes to be called Octopussy.

Lawson is by no means the first artist to explore the aesthetic potential of Mardi Gras beads. Back in the early 1980s, Jesselyn Zurik, an established New Orleans artist best known for wood sculptures, covered a 1974 Gremlin, to arresting effect, with Mardi Gras beads (it’s now on display at the Mardi Gras Museum in Kenner, La.). She also beaded elaborate, swirling patterns on flat wooden panels cut in the shapes of dresses. And for as long as there have been Mardi Gras beads, crafty types have used them to embellish costumes, votive alters and all manner of decorative objects.

Still, it’s a safe bet that no one has developed the medium as fully as Lawson. Says he, “I’ve got the expertise of manipulating the bead to the point where if I have an image in mind, I can now translate it comfortably.”

Zulu coconuts

Ever since his first Mardi Gras, Lawson has felt a special affinity with the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club.

A native of Birmingham, England, Lawson says his infatuation with beads began with a “big hallucinogenic Mardi Gras trip” in 1984, when he was an undergraduate studying landscape architecture at Louisiana State University, in Baton Rouge. He and a group of friends hit the Big Easy the weekend before Fat Tuesday. They didn’t have a place to stay, so the plan was to return to Baton Rouge after one night of music and revelry. But when it came time to drive back, Lawson, along with a cohort, decided to part company with the rest of the crew. The duo proceeded to embark on a party marathon, staying up for five days without a wink of sleep—hanging out in bars and carousing the French Quarter.

It wasn’t until the morning of Fat Tuesday that Lawson and his friend caught their first parade—Zulu. Beholding the rowdy burlesque of the face maskers in grass skirts, while in the throes of an extended acid trip, was, recalls Lawson, “pretty scary, not knowing that much about it.”

But as luck would have it, the god who looks after tripping fools was smiling down on Lawson that day: A Zulu masker handed him a “Golden Nugget”—i.e., a Zulu coconut, the most fabled throw in all of Carnivaldom.

Later on, after the last parade had passed, Lawson and his friend found themselves at the intersection of St. Charles Ave. and Napoleon Ave. Beneath a sun-drenched sky, Lawson recalls, Mardi Gras beads literally covered the street like a spangled carpet.

“It was the most visually explosive thing I’d ever seen in my entire life….That was when the visions first started happening.” It was, he adds, “such an amazing, intense arrangement of colors.”

The image became embedded, like a Jungian archetype, in Lawson’s psyche, though it wasn’t until years later that he began to translate his beaded flights of fancy into singular works of art.

Lawson never did graduate from LSU. Returning to England, he decided that painting landscapes, seascapes and cloudscapes was more to his liking than pursuing a career as a draftsman. His first exhibition, entitled Escapes, was at the Dunheved Gallery in Launceston, in the southwest county of Devon, in 1986. During this period, Lawson’s oil-on-canvas subjects reflected a concern with the transitory, ethereal quality of the natural world, and humanity’s precarious relationship to it. A subsequent show, at the New Street Gallery in Plymouth, was entitled Is There a Place that Haunts You?

From picturesque swampscapes to grim urban realities

By 1987, Lawson was ready for a change of scene. Drawn to the bucolic swamps between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, he relocated to Sunshine, a small fishing community in Eberville Parish where he lived rent-free, courtesy of friends who owned an old Mississippi River plantation property, and absorbed the ebb and flow of local life while working as a bartender at a picaresque joint called Miss Arlene’s Alligator Hilton Bar. In his spare time, he painted swampscapes and slices of Cajun life, among other subjects. He also executed mixed-media compositions that explored the interaction between the natural sciences of biology and geography as well as technological products such as latex and neon. Many of his initial works from this “bayou” period were included in a retrospective show at New Orleans’ Bienville Gallery, in December 1990.

By then he was living in Baton Rouge. Socking away money earned from odd jobs and sales of his work, Lawson was able to finance excursions to Guatemala and Mexico. Eventually, he lined up a job at a store in New Orleans that sold ethnic clothing and craft items. Before moving, he sold his van and used the proceeds to visit Indonesia, where he prospected for merchandise for the store and studied the art of shadow puppetry.

In New Orleans, Lawson took up residence in an Uptown neighborhood on Magazine St. He’d been living there for about six months when an incident of shocking violence rocked him to the core.

One day, eleven-year-old Ivory Simms—who often dropped by store Lawson worked in to play musical instruments on display—was out on the street with a group of friends when members of a gang pulled up in a car. One of the occupants fired a hail of bullets from an automatic machine gun, killing Simms and injuring three others.

In memory of Simms—“a star athlete and a good student,” according to the New Orleans Times-Picayune—Lawson decided to paint a mural on the side of a local bar, the now-defunct Jackie’s II Lounge, where he’d been sitting when he heard the news about Simms. Depicting a set of hands reaching skyward toward a blue dove, the mural, entitled Love is the Message, One Day at a Time, represented a plea for harmony at a time when youth-on-youth violence had yet to become a burning issue in the city.

Simms’s death, followed by other incidents of gun-related violence involving children, politicized Lawson. After finishing the mural, he relates, “I was still kind of disgusted with all these kids being killed, so I started making baby coffins.” The three-foot-long wooden constructions, with doors that opened out like a kitchen cupboard, were designed to be hung on walls.

Lawson’s baby coffins

These wooden constructions, originally conceived as political statements against youth-on-youth violence, attained the status of chic novelty items.

In September 1996, a ground-breaking show, entitled Guns in the Hands of Artists, opened at the Positive Space Gallery in New Orleans. Brian Borrello, a politically active New Orleans artist, recruited 60 local artists to contribute works incorporating guns, or pieces of guns. The show, which included two of Lawson’s coffins and garnered extensive media coverage, was made possible in part by a local program whereby grocery vouchers and useful appliances could be exchanged for guns, which were then machined and rendered harmless. The following year, one of Lawson’s coffins appeared in The Art Exchange Show—which was billed as “an (alternative) alternative art fair”—in New York City.

Meanwhile, among hip collectors in New Orleans, the coffins attained the status of chic novelty items. But, says Lawson, “It just got so depressing, making baby coffins all the time. I just went kind of crazy over it.”

By 1996, Lawson was having trouble making ends meet. He wound up residing in a warehouse, with no heat or hot water, in a run-down neighborhood on Dryades St. “That was a miserable time in my life,” he confides.

Miserable, but not unproductive. A genuinely humble man who likes to work with his hands, Lawson busied himself carving designs on doors and working odd jobs in the carpentry and construction trades. Then along came an interesting artistic proposition in the form of an old upright piano.

The piano belonged to a friend, Pamela Cobb. She had accumulated a large stock of Mardi Gras beads. Why not try beading the paino?

Sketching designs onto the piano with colored pencils was the easy part. Lawson and Cobb then began the arduous, painstaking work of cutting up necklaces and affixing the beads with glue sticks—one bead at a time. After working off and on for several months, every square inch of the piano’s exterior, except for the keyboard, was covered with beads. Dominating one side was an image evocative of Mexico’s Day of the Dead celebration: a skeleton emerging from flames and holding a cross. On the other side was a burning sacred heart. Emblazoned on the front, underneath the keyboard: a fallen angel. Lawson dubbed the labor of love Mardi Gras Mambo, the title of an anthem made famous in the late 1950s by a band, The Hawkettes, led by keyboardist and songwriter Art Neville.

Indigenous inspirations

Bo Dollis of the Wild Magnolias

Mardi Gras Indians

Lawson found inspiration in a cultural tradition emblazoned on the aesthetic consciousness of New Orleans.—Photo ©Pat Jolly

When Lawson wasn’t hard at work snipping and gluing, he could often be found at the H&R Bar on Dryades St.—home base of one of the city’s most revered Mardi Gras Indian tribes, The Wild Magnolias.

Carrying on a folk tradition that dates back to the 1800s, Mardi Gras Indians are one of the true aesthetic and cultural wonders of New Orleans. For Mardi Gras, celebrants, typically from poor neighborhoods, spend countless hours making elaborately plumed, intricately beaded costumes, known as “suits,” which are reminiscent of the American Plains Indians and the beadwork of the Yoruba peoples of Nigeria. In Lawson’s opinion, Mardi Gras Indian finery, along with Mardi Gras parade floats, represent “some of the most incredible artwork in the United States.”

Lawson says he feels a close affinity to the Mardi Gras Indians, as well as another traditionally African-American Carnival institution—Zulu. “I’m the only white Indian in the city,” he chuckles.

One night, Lawson took some photos of Mardi Gras Mambo to the H&R. Examining them, Bo Dollis, chief of The Wild Magnolias, told the artist he was “blessed” and added, “This is beautiful, carry on doing it.”

“It was a big deal for me,” says Lawson. “I mean, I didn’t want to feel like I was copying the Mardi Gras Indians and their work.”

Encouraged, Lawson successfully petitioned New Orleans’ Contemporary Art Center to include Mardi Gras Mambo in a show. But unfortunately, Cobb didn’t feel she got enough credit as co-creator, causing some hard feelings. Later, while Lawson was spending time in upstate New York, the piano found its way to the Ugly Dog Saloon, at 401 Howard Ave., where it resides to this day. If any money changed hands, he never saw a dime of it.

Nevertheless, Lawson soon had his eye on another upright piano—this one owned by a woman named Oliva, who had a funky boutique on Magazine Street. When Lawson expressed interest in buying the piano, she reminded him of something he’d said several years earlier, long before he began work even gotten hold of the piano that became Mardi Gras Mambo.

Back then, there was a piano at the store just like the one Lawson was now looking to buy. He used to drop by to drink tea and listen to a man tickle the ivories on the old upright, known as a “barrelhouse” or “honky-tonk” piano in New Orleans. One day, Lawson walked up to the pianist and said, “Wouldn’t it be great to see one of these pianos beaded?”

Lawson paid Oliva $100 for the piano that became Temptation, a tribute to Tom Waits, who has a song by the same name. He beaded it as a commission for a bar in Baton Rouge whose owners had seen Mardi Gras Mambo. (Ending up back in New Orleans, the piano is now on display at Barrister’s Gallery, at 1724 O.C. Haley Blvd., just down the street from the warehouse where Lawson once lived and had the studio where he beaded it.)

Lawson knew exactly what he wanted to do with the money he pocketed from Temptation: buy a baby grand piano to bead. He found one he liked at an auction house. Price: $900, plus a couple of pieces of his artwork.

Lawson’s tribute to James Booker

Intricate and idiosyncratic, the artist’s beadwork shares a stylistic similarity to the music of a genius whose virtuosity wasn’t fully appreciated during his lifetime.

The piano became a vehicle for Lawson’s interpretation of the music and life of James Booker, the idiosyncratic “Piano Prince of New Orleans” who died an early death in 1983. Having lost an eye, supposedly in a drug-related incident, Booker, also known as “Gonzo,” wore a trademark eye patch adorned with a silver star. His portrait appears on the lid of the piano, along with a large red spider—Lawson’s salute to a collection of songs performed by Booker entitled Spider on the Keys. Around the side of the piano is a swamp motif depicting a heron, flamingo and swan. When viewed from a distance, the tableau suggests a larger theme: a river of music meandering through the swamps and into the Crescent City, filling the air as stars fill the sky at night.

Laid into the beadwork above the keyboard is a rare James Booker doubloon, given to Lawson by a friend. (Eventually, the piano—dubbed Junco Partner, after Booker’s theme song—found an appropriate buyer: David Jernigan, an accomplished keyboardist who has worked with James Brown and Sheena Easton.)

Lawson subsequently moved out of the Dryades warehouse and, after a stint at the Audubon, landed at another transient-type hotel, also on St. Charles Ave., called the C Note. “I had to move out of there after a guy got killed in the stairwell,” says Lawson, who wound up moving back into the Audubon.

Creative asylum at the Audubon

In late 1996, a friend of Lawson’s from LSU, Clinton Peltier, along with a partner, Jonn Spradlin, bought the Audubon with the idea of transforming it into a hip hangout for creative types, while still preserving its “juke-joint” character.

After taking over, Peltier and Spradlin decided to throw a party and promote it as Sleaze Box, with a tagline about the Audubon: “The sleaziest hotel on the most beautiful avenue on the world.”

The Audubon Hotel

In addition to nurturing undiscovered artists, it earned big reputation among cognoscenti of fringe subcultures.

Spradlin remembers the night vividly. A transvestite bartender performed to songs by Journey and Reba McIntyre. “And to the Journey song,” he recalls, “she did splits and was naked on that dirty floor, and we thought we were going to die. It was so hysterical.”

“It set the tone,” he adds. “For the few people who were there, the word was out.”

The Audubon began hosting shows featuring the work of undiscovered artists, some of whom painted elaborate murals on the walls and ceilings of the rooms upstairs in exchange for free studio or living space. Spradlin and Peltier further endeared themselves to artistic types by adhering to a non-commercial ethos: They wouldn’t take commissions on artwork sold at the shows, refused to display neon beer signs or other forms of advertising and were generally open to making creative accommodations—Lawson, for instance, agreed to display some of his artwork in lieu of having to pay his bar tab. Also encouraging the artists to “sort of think of the place as their own,” says Spradlin, was the fact that there wasn’t “a whole lot of structure” or “on-site management.”

Today, the Audubon has a well-deserved reputation as a haven for inspired kinkiness. Consider that in June 1999, 600 people paid a $5 cover charge to attend Fetish Fest. Sponsored by Mr. Blinky’s Adult Video store, and billed as “an erotically charged night of art, performance and fashion,” it featured an arousing collaboration between artists and fetishists.

Thanks largely to minimal on-site management and a consciously non-commercial atmosphere, artists “sort of think of the place as their own.”

“We put up plastic over the doors of the hotel rooms and cut a hole, like a peep hole,” says Spradlin. In each room volunteers enacted, er, depicted, a fetish.

“We had a foot fetish, an old-man-in-high-heels fetish, the stocks-and-locks and all that—you know, the bind-you-up fetish,” Spradlin continues, not to mention fetishes involving feathers, drag queens and sex toys. Also presented, on stage in the bar downstairs: what Spradlin describes as “a major dominatrix show.”

Though the scene at the Audubon has certainly taken on a higher profile of late, attracting a procession of photographers, videographers and other cognoscenti of fringe subcultures, Spradlin, who also owns the swanky Red Room on St. Charles Ave., says the “underlying theme” has remained constant: “It’s the place where you walk in and no one’s going to turn their head, whether you’re , white, pink, purple or etcetera.”

Amid this milieu of misfits and struggling artists—which in some ways is reminiscent of Night of Joy, the French Quarter bar depicted in John Kennedy Toole’s novel Confederacy of Dunces—Lawson took it upon himself to keep a watchful eye out for his brethren. Noting that the artist has a “kind of has this fatherly, authoritative side to him,” Spradlin says he took to calling him “den mother.”

“How’s the den mother today?” Spradlin would ask. “Tell me how the children are.”

Truth be told, the Audubon’s hipster “children,” just like the crowd that hung out at Andy Warhol’s fabled studio in New York in the 1970s, at times have exhibited a tendency to overindulge. And sadly, in February 1998, the hedonistic lifestyle promoted by the establishment wound up claiming the life of co-owner Peltier.

Before he died, Peltier, a serious collector of works by undiscovered artists, had commissioned Lawson to bead two antique mannequins. Lawson completed the pieces, along with a third mannequin, for Spradlin, who wanted them for his private collection.

A beaded fish for a

citywide art installation

Lawson found a variety of objects worthy of beading, from shoes and weight scales to mannequins and bongo drums.

With the money Spradlin paid him, Lawson was able to afford to have a phone installed in his room at the Audubon. “It meant so much to him, having some money,” says Spradlin. At the time, Lawson didn’t even have a bank account, so he wound up entrusting his funds to his patron. “I was his bank,” says Spradlin, who maintained a ledger to keep track of Lawson’s debits.

Continuing to hone his craft, Lawson began beading other objects, such as bongo drums and skulls, as well as flat panels. One of the panels, depicting legendary New Orleans voodoo priestess Marie Laveau, found its way into Bryant Gallery on Royal St.

Lawson had a prospective buyer in mind—an acquaintance who owned Marie Laveau’s Voodoo Bar on Decatur St. But Marlene Durel initially resisted the idea of even visiting the gallery, let alone buying something off the wall for her bar. “I never had to walk out my door to get anything special in that place,” she says. “I never had to go out my door to look for one thing. People came to me [with] special, priceless things, and let me have ‘em.”

Durel not only wound up buying the Marie Laveau panel, but became enthralled with the idea of having Lawson bead a piano for her. This after having seen Junco Partner (which, at the time, was on display at the same gallery).

About a year-and-a-half later, Durel was looking to open a new bar, Marie Laveau Voodoo Two. The owner of a bar at 346 Baronne St., in the Central Business District, had decided not to renew the lease. Durel, who has a gift for telepathy, felt a good vibe about the place, in part because it had an antique Stuyvesant baby grand piano, and acquired the lease. It took some convincing, though, to get the guy who was giving up the space to part with the piano. He was emotionally attached to the old Stuyvesant and initially rebuffed Durel’s offer to buy it, then finally gave in (without knowing what Durel had in mind to do with it). Price: $5,000.

Beading at the bar, Lawson started work on the piano in January 1999. Almost immediately, it drew the attention of people walking by on the street who’d see the work-in-progress through the window and decide to drop in. Surrounded by piles of Mardi Gras beads, Lawson labored over it for three months—10 to 11 hours a day, an average of six days a week.

When Mardi Gras rolled around, Lawson found himself having to keep a close eye on his beads—revelers staying at the hotel next door to the bar were walking in and absconding with them. The worst offenders, according to Lawson, were “elderly” people. “They’ll wait till you use the bathroom or go to get a beer,” he explains, “and then they will grab ’em.”

A stunning homage to a legendary priestess

Voodoo Blues

The metallic quality of Lawson’s beadwork and his imagery are suggestive of the intricate sequined mosaics found in Haitian artwork.

Lawson’s work is almost always inspired by native cultures, and Voodoo Blues is no exception. A portrait of Marie Laveau—dressed in a white robe with her arms outstretched—dominates the piano’s lid. Her angelic visage is framed by a garland of purple, green and yellow flowers. Her left hand holds a flame, symbolizing rebirth. Unfurling from her other hand, and coiling around the piano’s lid, is a red-nosed snake.

A voodoo ritual—featuring another snake, a chameleon, a bongo drummer and dancing figures—is depicted on one side of the piano; a swamp scene, with a frog and lilies, wraps around the opposite side. Thanks to the precision and tightness of Lawson’s beadwork, the imagery, as in a finely woven tapestry, is strikingly distinct. The overall effect is suggestive of the intricate sequined mosaics found in Haitian artwork.

The piano, imbued with sly touches by the artist, resonates in a highly personal way for Durel. On the front is a red bull, which Lawson included because Durel was born under the sign of Taurus. Above the keyboard is a small plastic slot machine taken from a throw Lawson found while scavenging on Fat Tuesday. “I put it on because Marlene likes to hit the machines,” he explains, “and she’s real lucky on ’em.”

Also appearing on the piano’s lid is an owl, whose feathers, Durel points out, are rendered in “one-of-a-kind beads”—a gift from street person named George, who used to wash the windows of Marie Laveau’s on Decatur St. The brown, teardrop-shaped beads are etched with lines and, when laid in next to one another, look just like feathers. Says Durel, “A lot of special people [have] given me certain beads that went on the piano.”

The piano’s bench is also something to behold. Lawson beaded it to cover his bar tab at Voodoo Two, and his girlfriend, Liz, covered the cushion with a silver lame material that, says Durel, “set the whole thing off. It almost looks like Liberace should be playing on that piano.”

No doubt the sequined crooner, if he were alive, would get a kick out of Voodoo Blues. Camp fashion-plate extraordinaire Elton John almost certainly would, though he might be hard-pressed to make Durel an offer she couldn’t refuse.

“No one could ever buy it from me,” she says. “I could be on skid row, and I wouldn’t leave the piano.”

More recently, Durel commissioned Lawson to bead a mannequin for her new poolhall bar, The Club Behind the 8 Ball, at 3715 Tchoupitoulas St. To help decorate the place, Lawson made a gift of an antique condom machine (though he’s holding on to another model, which he says he’ll probably wind up beading). Durel predicts good things for Lawson’s mojo.

“When I met John, I met somebody who was very wonderful—very good-hearted—and never thought so much of himself that he wasn’t able to give. He gives a lot…and he’ll always have luck and he’ll always have the right things happen to him.”

Take Five, commissioned for Ralph Brennan’s Jazz Kitchen at Disneyland

Lawson’s steadfast dedication to a medium with unproven commercial potential has started to bear fruit.

And as a matter of fact, things have indeed been looking up for Lawson, who now lives with Liz, a wig and hat maker, in a comfortable French Quarter apartment. Plenty of commissions are now coming his way. And, thanks to media exposure and his LawsonWorks.com Internet site, his visibility is on the rise

Venturing into the realm of pop art, he has beaded a series of antique bathroom scales. Suitable for wall hanging, they’re emblazoned with words, such “Bitch,” “Oh Well” and “I Luv You —“things,” explains Lawson, “that you would normally say to the bathroom scale, you know, when you stand on it.” One of them, Cutie Pie, has three winged, glow-in-the-dark king cake babies encrusted amid the beadwork.

In January 2000, 10 of Lawson’s scale works were featured in a show at the Quarter Scene Restaurant, at 900 Dumaine St. Its owner, David Favert, is an admirer of Lawson’s work. Hanging on a wall of the restaurant is one of the artist’s flat panels—a beaded portrait of the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo. Then there are the beaded tabletops that Favert commissioned from Lawson. One depicts dancing vegetables. The other is a portrait of Tennessee Williams, embellished with a streetcar and a French Quarter lamp post. Appropriately, it covers table #1, where the writer used to sit when he visited the restaurant.

In the summer of 2000, Lawson’s work received national exposure through the New Orleans installment of MTV’s popular Real World program. The idea behind the voyeuristic series: Arrange for a diverse group of young adults, who aren’t actors and don’t know each other, to move into a house together and then let the camera be a fly on the wall—recording their supposedly unscripted, “real-world” experiences and interpersonal dramas over a six-month period.

Scouting around for distinctive furnishings and objects d’art, the folks responsible for decorating the New Orleans MTV house got in touch with Lawson after having seen his beadwork on display at Barrister’s Gallery. They wound up negotiating with Spradlin to borrow a beaded mannequin from his personal collection and one of the panels for the Audubon Hotel’s bar top. (The panels had been completed but were not yet installed.) Also displayed in the house: one of Lawson’s beaded skulls.

Further evidence that the artist is well on his way to garnering wider recognition: a commission from the Brennan family of New Orleans, a veritable culinary dynasty, to bead a grand piano for a new restaurant, Jazz Kitchen, at Disneyland. It’s called Take Five—a nod to the song of the same name by jazz composer/keyboardist Dave Brubeck, and the fact that it’s the fifth piano the artist has beaded. The design includes musical notes, a large saxophone and flambeaux—the fuel-burning torches utilized in nighttime Mardi Gras parades.

Disco Don and its subject, Donnie Estopinal

The tightness and precision of Lawson’s beadwork yields strikingly distinct images.

In terms of aesthetics and clientele, Disneyland is a far cry from the Audubon Hotel. Just how far is made clear in a new documentary, Rise, which explores New Orleans’ vibrant rave scene and the impresario behind it—Donnie Estopinal, a.k.a. Disco Donnie, who is a friend of Lawson’s. The raucous film, billed as “an unforgettable journey into the heart of the New Orleans underground,” includes footage from Mardi Gras 1999 and interviews with some of the Audubon’s most notable denizens. One segment captures Lawson in his studio, on the second floor of the hotel, stomping around barefoot in a pile of Mardi Gras beads—a consecration ritual of sorts, in which he partakes before starting a major piece of beadwork.

After the film was shot, Lawson decided to bead a flat-panel portrait of the rave party promoter. Entitled Disco Don, and measuring 5 feet by 4 feet, it shows the subject striking a pose in a disco suit, amid ascending spacecraft reminiscent of Flash Gordon. When Disco Donnie saw the finished piece, he “loved it,” says Lawson, “and immediately bought it.” Subsequently, the image was incorporated into a poster promoting a screening of the film at the CMJ Filmfest in New York City.

Rise is sure to enhance the Audubon’s infamous mystique. Yet Lawson maintains that the place isn’t as “scary” as some people might think. Noting its prime parade-viewing location on St. Charles Ave., he says “it’s the best place to be during Mardi Gras. It’s open 24 hours, and if you get really tired, you can rent a room.”

MardiGrasTraditions.com