King Cake: A Rich Tradition

Long before the Lord of Misrule reigned over the first pageant of the Twelfth Night Revelers in New Orleans, his ancient ancestor, the King of Saturnalia, set the precedent for a tradition that holds the key to understanding how a toothsome treat — king cake — became one of the most universal, and hungered for, symbols of Mardi Gras and New Orleans.

King Cake History: A Rich Tradition

The golden bean of the Twelfth Night Revelers

Perpetuating the illusion that the Goddess of Chance exerts her will through the “luck of the bean.”

The writer Robert Tallent once described Carnival as “a mock revival of monarchic rule,” and every year in New Orleans the thrills and glories of this make-believe world begin anew on January 6, also known as Twelfth Night, with the Twelfth Night Revelers bal masque.

To the casual observer, it might seem a strangely formalized, if not downright quaint, spectacle. But at its heart is a ritual that is key to understanding how a sticky, coffee cake-type pastry — king cake — evolved into one of the most recognizable, and hungered for, symbols of New Orleans and Mardi Gras.

The gist of the Twelfth Night Revelers’ (TNR) proceedings, though subject to variations from year to year, unfold more or less as follows: Not long after a curtain is raised to reveal his majesty, the Lord of Misrule, krewe members attired as pastry chefs wheel out an enormous mock cake aglow with “candles” (actually electric lights) and pantomime cutting it with large faux baker’s knives made of wood. Depending on how lively they’re feeling, they might even stage a sword fight.

The song “Thank Heaven for Little Girls” is the cue for the “Cake March” and first dance, which are reserved for single women seated in the call-out section on the main floor. One by one, as their names are announced, or “called out,” they’re escorted by a committeeman to the masked krewe members who requested the favor of the dance.

The masker in turn leads his “call out” to the cake, which is chock-a-block with small boxes. Each box contains either a small piece of real cake or a bean on a chain. As orchestrated by krewemen, who are assisted by preteen boys got up as “junior cooks,” only the debutantes designated to serve as maids in the court receive boxes with beans. All but one of the debs is handed a box with silver bean. Whoever receives the box with the gold bean, is crowned queen.

This being the realm of make-believe, the fact that her royal fate is actually predetermined is beside the point: The ritual is designed to perpetuate the illusion that the Goddess of Chance has exerted her will through the “luck of the bean.” That everyone knows it’s a rigged game, however, doesn’t mean that the recipient of the prized trinket won’t be utterly surprised. Indeed, much depends on how well her parents, who traditionally host a pre-planned party after the ball, keep the secret.

One of New Orleans Carnival’s most socially elite organizations, TNR held its first pageant on January 6, 1870 — a parade and tableau ball entitled “Twelfth Night Revel.” (Botched orchestration in serving cake that year resulted in a famous footnote to Mardi Gras history. More on this later.)

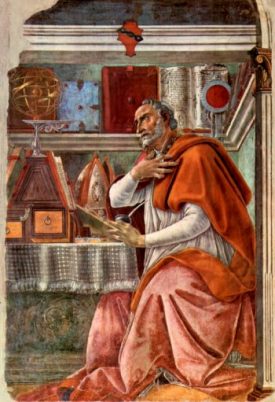

St. Augustine fresco by Boticelli

Thanks largely to his preaching, Twelfth Night became a holiday imbued with royal associations.

In drawing inspiration from the historical customs associated with making merry on Twelfth Night, the Revelers owed a debt to early Church fathers and, more specifically, St. Augustine. As Bridget Ann Henisch explains in her exquisitely rendered book Cakes and Characters: An English Christmas Tradition, it was during the reign of Roman emperor Aurelian, in the late 3rd century, that December 25, the winter solstice of the Julian calendar, was declared to be the official birthday of the divinity Sol Invictus, the Invincible Sun. “Soon afterwards the Church made a poaching raid into enemy territory,” writes Henisch, and “seized the day for its own.”

In the story of the Epiphany, as related in the gospel of Matthew, “three wise men from the east” visited the baby Jesus in Bethlehem on the twelfth day following his birth. “An epiphany is a manifestation,” notes Henisch, “and January 6 became the day appointed by the Church to celebrate the revelation of Christ’s divinity to mankind.”

In the 4th century, the western world’s most influential preacher, St. Augustine, romanticized and embellished the story of the Epiphany. The gift-bearing wise men became “kings,” and Feast of the Epiphany, the twelfth day of Christmas, evolved into a major holiday imbued with royal associations.

Medieval monarchs would don their finest regalia, maybe even wager in a game of dice. Children received presents to commemorates the gifts given by the kings to the baby Jesus. In the great houses of Europe, the holiday became a glittering finale to a 12-day Christmas cycle, with elaborate entertainments featuring conjurers, acrobats, jugglers, harlequins and other humorous characters — notable among them the Lord of Misrule, whose task was to organize the festivities. In England — where the seasonal extravaganzas might include elaborate allegorical dramas, called masques, that paid homage to the monarch as a guardian of the state and a provider of peace and prosperity — he often was appointed on November 1, All Saints’ Day, to allow him time to prepare. His reign lasted throughout the 12 days of Christmas and, according to Henisch, sometimes even extended to the traditional feast day that serves as the overture to Lent: Shrove Tuesday.

While the Twelfth Night customs that spread throughout Europe were subject to numerous variations, one element transcended virtually every culture that observed the holiday: the choice of a mock king for the occasion. “The way he was chosen might vary,” Henisch explains, “but it was always a matter of chance and good fortune: lots could be drawn or, in the most widespread convention, a cake would be divided. The person who found a bean, or a coin, in his piece was the lucky king for the night. Sometimes he picked his own queen, sometimes chance chose her for him, and a pea secreted in the cake conferred the honor on its finder. The temporary change in status was sustained with ceremony; the king was given a crown, the authority to call the toasts and lead the drinking and, sometimes, the more dubious privilege of paying the bill on the morning after.

“Cake and King were thus linked together as good-luck charms for the coming year. The cake, the bean and the pea were emblems of fertility and harvest, health and prosperity…. His [the king’s] brief reign spanned the turn from one year to the next, and in his topsy-turvy kingdom conventions were triumphantly defied. Inhibitions were forgotten, characters changed, everyday restraints relaxed. The harsh certainties of life were softened in a haze of alcohol and high spirits.”

In the kingdom of Twelfth Night, the Bean King and the Lord of Misrule were in many ways kindred spirits, as both were expected to infuse the ceremonies with a lively esprit de corps. And in fact, they almost certainly share a common ancestor: the King of Saturnalia, the ancient Lord of Misrule, who presided over the Roman festival held in honor of Saturn, the god of agriculture and civilization.

Like other ancient observances tied to the winter solstice, Saturnalia commemorated the death and rebirth of nature. In its earliest, most barbarous form, human sacrifice was performed in hopes of insuring fertility and prosperity.

According to J.G. Frazier’s classic study of myth, magic and religion, The Golden Bough, “it was the universal practice in ancient Italy, wherever the worship of Saturn prevailed, to choose a man who played the part and enjoyed all the traditionary privileges of Saturn for a season, and then died, whether by his own or another’s hand, whether by knife or fire or on the gallows-tree, in the character of the good god who gave his life for the world.”

Eventually this practice gave way to the reign of a mock monarch whose duties were less hazardous. The manner of his choosing related to the mythology surrounding the god Saturn, whose reign was believed to be so just that there were no slaves or private property. Thus it was decreed during Saturnalia that all should be given equal rights, and indeed even a slave could rule.

Henisch: “Every member of the party had to obey the King’s command, and dance, or sing, or jump into a tub of cold water, at the royal whim.”

According to Patrick Dunne, a New Orleans-based dealer in culinary antiques and art who has delved deeply into the origins of and traditions of Twelfth Night, the King of Saturnalia was chosen by throwing dice, drawing a lot, or discovering a fava bean or coin in a piece of cake. For the Romans, the fava bean was not only a symbol of fertility but a dietary staple. “Some people believe the cake was actually made from the beans as well as having the bean in it,” says Dunne.

Society of St. Anne maskers on Mardi Gras 2003

The Dyonisian spirit of the ancient revels survived in the climatic finale of Carnival.

The festival of Saturnalia in the early years of the Roman Republic was observed on one day, December 17, but by the end of the first century A.D. it had morphed into a full week of gambling, feasting and pagan-style revelry. Soon after, the anticipation began to build for the Kalends, a New Year’s celebration that ran from the 1st to the 5th of January. “Groups of young men dressed up in animal masks and skins, or women’s clothes, and roared through the streets of Rome with the rude, rash boldness that disguises give their wearers,” writes Henisch.

Such customs had a lasting influence throughout the Roman Empire long after Rome itself had fallen. The Church’s condemnation of paganism notwithstanding, ancient rituals involving food and drink, character change and disguise, and the suspension of the usual social order during the reign of a Bean King were absorbed into Judeo-Christian tradition. In Europe, Carnival came to be more or less accepted by Church fathers as a necessary period of foolishness and folly before the fasting and abstinence of Lent. (Because the day before Ash Wednesday, which marks the beginning of Lent, was one of feasting, it came to be known as Fat Tuesday or, as the French would say, Mardi Gras.)

If the more raucous side of the old Dionysian spirit survived in the climatic finale of Carnival, the holiday variously known as Feast of the Epiphany, Twelfth Night or King’s Day offered refinements on familiar themes and symbols. Hence the passion for masquerading on Twelfth Night that arose in Italy during the Renaissance and then spread to France and England. Bals masques became the vogue.

And “Twelfth cake” continued to be a source of enchantment, as the holiday became an occasion for bakers to promote their art — not only in shop windows but also by parading their creations through the streets. Illustrations and detailed, rhapsodic descriptions of lavishly decorated specimens would appear in the Illustrated London News.

For some confectioners, however, size was the true badge of nobility. Henisch cites an 1811 advertisement boasting of an “Extraordinary Large Twelfth Cake” that, measuring 18 feet in circumference and weighing “nearly half a Ton,” was “ready for Public inspection.”

In England, the rise of Twelfth cake as an object of veneration coincided with the decline of the old method choosing mock royalty. By the 1830s, according to Henisch, the bean and pea were no longer buried in the cake, and so the frenzied search for them, which sometimes resulted in culinary carnage, was no longer part of the game. The excitement had shifted, instead, to a bowl, hat or bag containing slips of paper or illustrated cards, each denoting a character whose name typically defined an identity (e.g., King, Queen, Fanny Flirt, Jerry the Jester, Sir Arthur Argue, Miss Sprightly, Lord Dashaway). Each member of the party would pick one out and thus have a chance to shine as someone else.

As the new ritual caught on, caricature fever swept England. Everyone collected prints, cards, card wrappers and envelopes with witty, satirical, naughty designs featuring Twelfth Night cakes and characters. The cake which often dominated the wrapper designs was used as a billboard to comment on everything from military victories and affairs of state to royal occasions and ballooning exploits.

The century between 1760 and 1860 marked the heyday of Twelfth Night in England. But as the Industrial Revolution kicked in, curtailing the time available for an extended season of frivolity, Christmas and its attendant commercial possibilities began to take center stage. Trees, Christmas cards and new kinds of books for children, along with traditions such as Bringing Home the Yule Log, Hanging up the Holly and Kissing Beneath the Mistletoe, usurped the prerogatives of Twelfth Night’s cast of characters. As Henisch puts it, “Christmas day was transformed from the first scene into the grand climax of the drama…,” leaving Epiphany marooned. Traditional Twelfth cake was replaced by a full-blown Christmas dinner with a large plum pudding.

A collection of porcelain French king cake dolls

Descendants of the fava bean that pre-Christians concealed inside a celebratory cake, for the purpose of selecting a mock king.

But in Continental Europe, where the Roman Empire left a more lasting legacy, the ancient traditions associated with the winter solstice and Epiphany endured. The ritual of hiding a tiny treasure in the celebratory cake was, indeed, a symbolic reenactment of Epiphany. In France, the bean — la feve — eventually was replaced by a bean-sized baby Jesus; its discovery commemorated the discovery of Jesus’ divinity by the Magi. Legend has it that the cakes were made in the shape of a ring and colorfully decorated to resemble a bejeweled crown.

It became a tradition to serve the cake with paper or cardboard crown on top. Whoever found the hidden trinket, would get to wear the crown and choose a consort.

Today, the most popular variety of king cake in France is the couronne, French for “crown.” Round like a doughnut and made with sweetened, egg-enriched brioche dough, it comes decorated with coarse granular sugar, red- and green-glazed cherries and a golden apricot glaze. The trinkets, meanwhile, have become a phenomenon unto themselves. Each year brings new variations — entire sets of highly anticipated collectibles, which are aggressively promoted by bakers.

Given the deep historical roots of France’s pre-Lenten pastry obsession, it’s hardly a coincidence that among the colonial outposts of the New World, no city embraced Twelfth cake, or king cake, with as much fervor as New Orleans. Creoles, as New Orleanians of French and Spanish decent took to calling themselves, adopted the French Twelfth Night cake custom and melded it with their party-loving ways — in particular, the Spanish custom of throwing grand balls where a king and queen were chosen.

By the late 18th century, a season of balls, called les bals des Rois (the balls of kings), was well established. On Twelfth Night, the celebrants would wait until the stroke of midnight to cut the cake — a French-style pastry, gateau des Rois, filled with frangipane (made from almond paste, eggs, butter and sugar). Inside was a bean, almond, pecan or perhaps even a jeweled ring.

If a queen was crowned, according to the Times-Picayune‘s Creole Cook Book, she would choose her consort by presenting him with a bouquet of violets. But if a man found the hidden token, the women would parade in front of him. As recounted in The Creole Cook Book, originally published in 1901, “He would take his stand near the mantel, the music would strike up, and the beautiful promenade around the room would begin, the gentlemen gracefully offering their arms to the ladies, the latter laughingly complying with the old custom of passing before the king while he chose his queen.

No doubt there was much secret vexation among these bonny girls as they passed on and on, the king seemingly unable to make a choice. Suddenly he advanced, and taking a flower from the lapel of his coat, he presented it to the lady, and, if it happened to be a ring in the cake, often as not it was a magnificent diamond, too, that he passed to her.”

A merry-go-round of balls would follow, ending on Fat Tuesday. Each week a new king and queen were crowned. The reigning queen would host the next gala at her home; the king, however, was expected to foot the bill.

New Orleans-style king cake with fondant icing

Once primarily a vehicle for the ritual enactment of selecting mock royalty to reign over Carnival or Twelfth Night festivities, king cake is now valued as a delicious food item — a tasty excuse to cut loose.

While the early pre-Lenten festivities in New Orleans were dominated by Catholic Creoles, the founders of the first Carnival societies, or krewes, were Protestants of Anglo-Saxon descent. Accordingly, English Twelfth Night traditions became a source of inspiration for the members of the Mistick Krewe of Comus, founded in 1857, and the Twelfth Night Revelers.

The theme of the 1859 Comus pageant was “The English Holidays.” As described in Henri Schindler’s book Mardi Gras: New Orleans, “The cast, all afoot, marched inside towering papier mâché creations depicting Twelfth Night, May Day, Midsummer and Christmas. The Lord of Misrule was accompanied by the Abbot of Unreason with Cards, Chess, and other games of chance; an enormous Twelfth Cake, its bottom layer almost touching each curb on the narrow streets, struggled forward to deafening applause.”

In 1870, the Twelfth Night Revelers debuted with a procession of floats, or tableaux roulants (rolling tableaux), followed by a ball at the New Opera House, where the first queen in New Orleans Carnival history was due to be anointed. But after a gigantic cake containing a gold bean was rolled out and sliced, things quickly got out of hand. An attempt was made to distribute slices from the ends of spears that some of the krewemen had carried in the parade; slices were also reportedly thrown to ladies sitting in boxes. If any lady found the bean, she did not step forward. Quite possibly, the trinket was simply lost amid the confusion.

At the ball the following year, the Lord of Misrule wasn’t about to leave anything to chance. Indeed, writes Schindler, he “knew which slice contained the bean, and when he saw the young lady receive it, strode to her and before the assembled guests, crowned her Queen of the Ball.”

Because Carnival is a highly dynamic phenomenon, traditions are constantly being reinterpreted and invented anew. In the case of TNR, even though the real cake wound up being replaced by a mock cake, the “luck of the bean” ritual has endured.

While the practice of using king cake to divine royalty was never widely imitated by other Carnival krewes, the toothsome treat nevertheless became more than just a symbol of the festivities: At king cake parties, generations of New Orleans children became familiarized with mock royalty — a concept fundamental to the rituals of Carnival — and teenagers learned the social niceties of drinking, dancing and mingling with members of the opposite sex.

When the cake was served, if a girl found the lucky token — in time the bean was replaced by a porcelain doll, which in turn gave way to a plastic “baby” — she was obligated to have the party the following week. The young man she designated to be her king was responsible for supplying the king cake. Accordingly, if a young man found the token, he would designate one of the girls to be his queen. However, in keeping with the prevailing custom of the reigning queen assuming the role of host, she’d still be expected to throw the next party.

Alas, times have changed. Nowadays, teenagers are more likely to have king cake in school than at king cake parties hosted by their peers. As for adults, offices have become a prime venue for seasonal rituals involving king cake.

The cakes themselves have changed, as well. The almond-paste-filled pastry puff that’s traditionally associated with northern France — the gateau des Rois enjoyed by the old Creole gentry in New Orleans — can still be found at some specialty bakeries. But by far the most popular style of king cake these days has more in common with the Bordeaux Twelfth Night cake of southern France — the aforementioned couronne, which is made from brioche dough. (Key differences: the New Orleans version is rolled with cinnamon and, instead of being glazed, comes covered with purple, green and gold sugar or sprinkles, sometimes atop fondant icing.)

New Orleans bakers, a decidedly restless and competitive breed, are generally more prone to experimentation and innovation than their more tradition-minded Gallic counterparts — at least when it comes to king cake. Chocolate, blueberry, cream cheese, pecan praline, even crawfish — these are but a tiny fraction of the fillings now offered in New Orleans-style king cake.

Moreover, king cakes come in shapes and colors to complement just about any holiday or special occasion. So, for example, a Christmas king cake might be formed and decorated to resemble a wreath, while a birthday king cake might be made in the shape of numerals.

And while in France the trinkets are more varied and collectible, the New Orleans king cake baby has evolved into a beloved mascot of Mardi Gras. Thus, plastic babies in metallic purple, green and gold now adorn beaded Mardi Gras necklaces, while babies cast from gold and silver are used in lines of jewelry. There are black babies, glow-in-dark-babies with angel’s wings and handcrafted babies used for costume accessories or decorative baubles.

Meanwhile, thanks to the advent of express-shipping services, New Orleans king cake culture has spread throughout the United States and beyond. As a result, “I got the baby!” — the cry announcing that a party-goer has received the slice of cake with the baby — is literally, during Mardi Gras time, heard around the world.

MardiGrasTraditions.com