Everybody knows that Mardi Gras is a time to frolic and have fun, to cut loose — to “throw down,” as they say in the Big Easy. But what about the trappings and traditions — the masks, beads, king cake and pretend royalty; the ubiquitous purple, green and gold? Mardi Gras customs and traditions comprise a rich mosaic that draws on a wide variety of art forms, topical motifs and historical precursors.

2009 Big Shot Brian McMillan strutting in style at the Zulu Lundi Gras Festival

Like other notable Zulu Carnival characters, the Big Shot, whose trademarks are a large cigar and a derby hat, is an elected position. He typically spends a small fortune on flashy finery, including signature Big Shot throws

Carnivaldom is a realm unto itself, with a peculiar lexicon and a cornucopia of highly evolved customs and traditions that comprise a cultural repertoire or “tool kit,” whereby different themes, motifs and symbols are continuously cobbled together, recycled and reinterpreted. Which is why Mardi Gras is a highly dynamic phenomenon, allowing plenty of freedom to improvise and reinvent.

In New Orleans, Carnival — the season of festivity and rejoicing that culminates on Fat Tuesday (Mardi Gras) — is the time of year when most everyone becomes an artist. A lot of the fun, to be sure, comes from seeing how the city’s famously inventive citizens are always finding new ways to work with what’s in the tool kit —inventing new traditions while still bonding in some way to the framework of established Mardi Gras conventions. The results can be entertaining, sometimes even enduring.

Take the Mystic Krewe of Barkus.

Humans have a popular Mardi Gras parade called Bacchus. Why not give dogs their own parade and call it Barkus? This flight of fancy, conceived in 1993, took root and evolved into a fundraiser for assisting abandoned and abused animals.

Canine royalty reign over the proceedings, with all the requisite trappings and accoutrements enjoyed by their two-legged Mardi Gras counterparts: a royal court with doggie dukes and duchesses along with elaborately festooned parade floats accompanied by marching bands; plus royal proclamations, Champagne toasts, media photo ops, chauffeured limousines — the works. Such is the New Orleans mind-set when it comes to elaborating on the Mardi Gras “tradition.”

A big crowd pleaser, Barkus is now a venerable and beloved institution that has spawned imitators in other cities. Past themes have included “Jurassic Bark” (1994), “Lifestyles of the Bitch and Famous” (1995), “Tailtanic: Dogs and Children First” (1998), “Joan of Bark” (2000), “Saturday Bite Fever” (2001) and “Indiana Bones: Raiders of the Lost Bark” (2008).

Disco DJ Taco in “Saturday Bite Fever,” Mystic Krewe of Barkus 2001

What began as a seemingly wacky flight of fancy is now a venerable and beloved Mardi Gras tradition.

In one sense, Mardi Gras is simply an excuse to cut loose — to revel in the risqué, engage in merry mockery and let pleasure rule. But it’s also a time to indulge obsessions and partake in collective manias — hence the term “Mardi Gras Madness.” The colors of this madness are purple, green and gold, a combination that’s woven deeply into New Orleans’s renown culture of revelry.

History doesn’t record the exact reason why the Rex Organization, in making its Mardi Gras debut in 1872, adopted the scheme, though Errol Laborde, in his book Marched the Day God: A History of the Rex Organization, plausibly asserts that the krewemen were guided by the laws of heraldry.

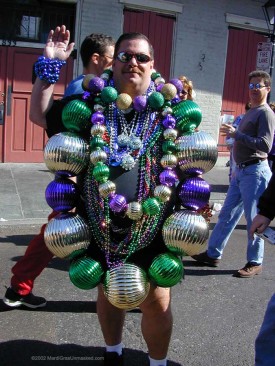

In any case, purple, green and gold captured the public’s imagination and — often in combination with mask, crown and jester imagery — have become a way for citizens of the realm to revel in decorative frenzies.

Throws are also a big part of Mardi Gras Madness. The thrill and challenge of acquiring beads and other coveted gewgaws is a competitive sport — bringing ecstasy and fulfillment, however fleeting — and even old folks and mild-mannered ladies in evening dresses push and grovel for a piece of the action.

The spectacle might seem dangerously maniacal if it wasn’t so darn entertaining.

Want to increase your harvest of the flashy spoils? Check out Tips & Tricks.

What about the infamous Mardi Gras barter economy on Bourbon Street?

There’s some madness for you. In the view of certain native cognoscenti, the rampant exploitation of the boobs-for-beads free-for-all by media outlets and video producers has tarnished the city’s image and overshadowed the traditional family orientation of Mardi Gras.

But like it or not, Mardi Gras immodesty has become a leisure activity and a bona fide tourist attraction.

In New Orleans, the act of costuming is known as “masking,” and it is this ability to escape the prosaic, through a ritual transformation of one’s identity, that bestows the exhilaration and magic inherent in the words “Mardi Gras.”

Costumes incorporate and interpret a mind-boggling array of themes and images from myth, literature, pop culture, religion, politics and society, while also expressing or disguising the dreams, fears and fantasies of the celebrants.

As exemplified by Mardi Gras Indians, creative expression through performance and masquerade is a consuming passion and a way of life. The process of making a Mardi Gras Indian “suit,” which can take up to a year and cost thousands of dollars, brings families and communities together in a collaborative artistic endeavor.

The results are stunning: the vibrant colors of dyed ostrich, coque and marabou feathers, which recall the ceremonial attire of Plains Indians, are complimented by intricate, pictorial beadwork — the stylistic origins of which can be traced back to West Africa and the Caribbean — or sculptural (raised-relief) designs set off with dazzling arrays of beads and crystals.

Other Mardi Gras pastimes include parties and balls, music, parades, king cake and drinking. Note that the history of king cake reveals a lot about the origins and evolution of Mardi Gras. Long before the Lord of Misrule reigned over the first pageant of the Twelfth Night Revelers in New Orleans, his ancient ancestor, the King of Saturnalia, set the precedent for a tradition that is key to understanding how this toothsome treat became one of the most universal, and hungered for, symbols of Mardi Gras and New Orleans.