The nexus between Carnival and music reflects the festive, let-the-good-times-roll culture of the Crescent City, where parading and dancing have long been obsessions. The seasonal spirit and its accompanying soundtrack conspire to prompt revelers to shed inhibitions and “throw down.” “All because,” in the immortal words of Al Johnson, “it’s Carnival time, and everybody’s having fun.”

A bounteous cornucopia of joyful noise

The Storyville Stompers Jazz Band, and musical friends, rolling with the Society of St. Anne on Carnival Day 2011

The joyous license of New Orleans parade music goes hand-in-hand with rollicking, devil-may-care spirit of Mardi Gras.

Mardi Gras music, like Christmas music, is not so much a style of music as it is an aural milieu comprised of various forms. Among them: orchestral and big-band arrangements played at tableau balls; Mardi Gras-themed rhythm-and-blues numbers that pour out of jukeboxes, “cutting-loose” jazz tunes that drive revelers to “shake booty” and pump umbrellas in the air; Afro-Caribbean chants and percussive rhythms associated with Mardi Gras Indians; and parade-time beats from school bands marching between floats in parades.

The nexus between Carnival and music reflects the festive, let-the-good-times-roll culture of the Crescent City, where parading and dancing have long been obsessions. “The desire for celebration is part of New Orleans culture,” scholar and clarinetist Michael White once remarked on a radio program. “We parade at the drop of a hat for just about any event you can imagine: you get married, you die, if someone is born. We parade sometimes just for the sake of parading. And people get out and dance; that’s what the spirit is all about.”

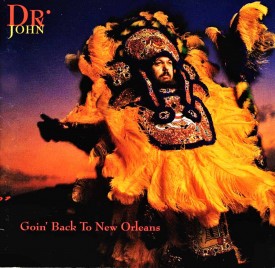

Indeed, this spirit of joie de vivre — i.e., the Mardi Gras spirit — is almost a precondition of the sounds for which the Crescent City became famous. As Dr. John — arguably the foremost living interpreter of the city’s musical traditions — observes in the liner notes for his Grammy-winning Goin’ Back to New Orleans album, “New Orleans music was not invented, it just kind of grew up naturally, joyously, just for fun.”

Being a musician in New Orleans is all about having fun with the music, and at no time is this more evident than during Carnival season. The same Mardi Gras spirit that prompts revelers to shed inhibitions and seek ritual transformation has a way of encouraging playfulness and spontaneity on the bandstand, as well as countless variations on old Carnival favorites such as “Carnival Time,” “Hey Pocky Way,” “Second Line,” “Go to the Mardi Gras” and “Big Chief.” And it seems that almost every year brings the release of new would-be anthems, as bands try to repeat the feat of the ReBirth Brass Band, whose infectious brass/funk number “Do Watcha Wanna” exploded during Carnival 1991. Thus, the Carnival songbook is continually expanded and reinvented, helping fuel a brisk business in releasing the Mardi Gras equivalent of Christmas-music anthologies.

As long as there have been parades, dances and balls in New Orleans, there has been a steady demand for musicians. “Carnival, by providing the audience, the money, and the forum in which to develop music and musicians, helped create the New Orleans music tradition,” historian Reid Mitchell, in his book All on a Mardi Gras Day: Episodes in the History of New Orleans Carnival (Harvard University Press, 1995), points out.

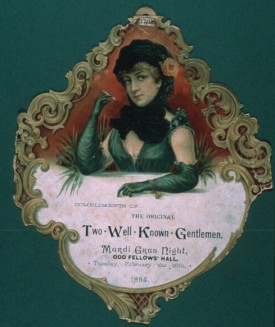

An 1895 invitation to the Ball of the Two Well Known Gentlemen

An infamous affair catering to the New Orleans underworld, it was frequented by “sporting men,” prostitutes and even women of “good standing,” who took advantage of the anonymity afforded by the mask.

— Photo courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum

New Orleans was a ball-mad city long before there were organized Carnival parades. French and Spanish colonizers reveled at fancy-dress and masquerade balls in the 1700s. As the Carnival season of merriment became more established, impresarios staged public balls catering to various strata of society, while upper-crust Creoles held rounds of private balls in which kings and queens were selected and courtly rituals observed.

“The idea was to get in as much fun as possible before Lent,” explains Henry A. Kmen inMusic in New Orleans (Louisiana State University Press, 1966), “and in New Orleans fun meant dancing: ‘From the very commencement of the Carnival,’ wrote one onlooker, ‘there was no thought of, no occupation, no interest in anything except dancing.’ This observer counted as many as eleven balls on a single evening, listened to night-long music on every street corner, and concluded that at this time of the year no man in New Orleans was ‘his own master; he must belong, body and soul, to the ballroom.’ ”

The fact that “New Orleans was replete with ballrooms unsurpassed in size and splendor anywhere,” according to Kmen, sparked spirited competition for patrons. “But the ballroom proprietor who perhaps showed the most ingenuity was the owner of the Jefferson Ballroom. In 1822 he turned his masked balls into gassed balls by giving ‘exhilarating gas’ (nitrous oxide) to the dancers… all to the accompaniment of ‘good music.’ ”

Musicians had to be exceptionally versatile to accommodate a dizzying variety of dances steps. Kmen mentions boleros, gavottes, cotillions, gallops, waltzes, mazurkas, reels and minuets, “to say nothing of the ever-present French and English quadrilles…”

But without a doubt, notes dance scholar Jennifer Atkins in her 2008 Florida State University PhD dissertation, Setting the Stage: Dance and Gender in Old-Line New Orleans Carnival Balls, 1870 – 1920, the waltz was the most popular Carnival ball dance in the latter half of the 19thcentury. “Sexually enticing encounters on the dance floor were enhanced by the trance-like abandon of the waltz,” she writes. “Men and women were drawn to each other through the sheer centrifugal force of their dancing.” She cites a report in the New Orleans Daily Picayuneabout the 1877 Mistick Krewe of Comus Ball. It rhapsodizes about dervish-like women in “dreamy embraces through the mazes of mysterious terpsichorean figures,” while “delightful music lulled their senses into delicious bliss” amidst “brilliant costumes worth a world of money” and an “enchanted display of magnificence and royal splendor.”

Music has always been integral to choreographed elements of Carnival balls: royal entrance, performance of tableaux, court presentation, promenade and grand march. Evocative of ceremonial displays of royal pomp in Old Europe, the grand march in context of a Carnival ball is a symbolic affirmation of elevated status — a regal display worthy of the assembled guests’ admiration. The epitome of this ritual occurs at the Meeting of the Courts on Mardi Gras night, when Rex and Comus, in a display of opulent pageantry, escort each other’s queens around the ballroom. They waive their scepters in acknowledgment of the approbation of their “subjects,” while the orchestra plays the grand march from the opera Aida.

Rex and consort serve as the de facto king and queen of Carnival, and their ball entrance is always accompanied by the formal cadences of the original Carnival theme song, “If Ever I Cease to Love.” Originally published in London in 1867, according to the 1989 edition of Arthur Hardy’s Mardi Gras Guide, it was written by George Leybourne, who also wrote “The Man on the Flying Trapeze,” and popularized in America by a British singer, Lydia Thompson, who, coincidentally, performed in New Orleans during Mardi Gras 1872. It is a silly but catchy ditty whose lyrics include the line “May the moon be turned to green cream cheese, if ever I cease to love.”

The 2002 King of Carnival

Reigning over a kingdom with a sentimental attachment to the song “If Ever I Cease to Love.”

Stoking anticipation for the 1872 debut of Rex, whose parade would became the focal point of daytime festivities on Mardi Gras, the New Orleans Times published tongue-in-cheek edicts and tidbits dispatched from his mythical realm on Mount Olympus. One article noted that he was a bachelor who believed matrimony “should not be entered into until experience has sobered the liveliness of youth and all the wild oats have been sewn.” Indeed, hearts were all aflutter in his mysterious kingdom, where, according to the article, ladies were “already overwhelming His Majesty…

“It is well to note in the latter connection that the national air or anthem of the Carnival Dynasty, for many centuries past, has been, as is at present, ‘If ever I cease to love.’ ”

Rex’s adoption of the song may have been prompted in part by the highly anticipated visit to New Orleans of real royalty. On a tour of America, Russian Grand Duke Alexis Romanoff had supposedly become smitten with Thompson after having seen her perform the song in a popular musical comedy called Blue Beard. He was a guest of honor at the inaugural Rex parade, seated at Gallier Hall on St. Charles Avenue.

According to the Rex Organization website, “Legend has long romantically linked the Grand Duke with the singer, and suggested that “If Ever I Cease to Love” was performed for the Grand Duke because of his romantic interest in Miss Thompson. While this is a good story, it is probably not quite true. Bands performed the Russian national anthem for the Grand Duke, and when Rex dismounted on Canal Street to review the parade the bands played “If Ever I Cease to Love.”

“If Ever I Cease to Love” has received jazz treatments from the likes of clarinetist George Lewis and his Original Zenith Brass Band, Edmond “Doc” Souchon and Johnny Wiggs and his New Orleans Kings. A version of the song akin to what’s played at the Rex ball can be heard on the album Jimmy Maxwell and his Orchestra: At the Mardi Gras Ball. Charmaine Neville, of the famous New Orleans music family, includes a soul-inflected rendition on her album Queen of the Mardi Gras, while guitarist John Rankin offers a lilting solo acoustic version on the album Fess’ Mess. Nevertheless, despite often being referred to as the “anthem of Carnival,” it hasn’t been recorded or included on genre compilation albums nearly as often as other songs that would become classics of the Carnival canon.

If the music played at Carnival balls in the 19th century reflected mostly a European sensibility, as required by the preferred styles of dance, the sounds heard in streets were taking on a more polyglot complexion. Long before the swinging polyrhythms known today as New Orleans jazz materialized in the early decades of the 20th century, the Crescent City was a crucible of musical cross-fertilization. What would eventually come to be known as “Creole” music was an expression of this blending of African, Native American, Caribbean, French and Spanish influences. The early brass were a reflection of this “creolization,” playing a medley of popular and folk songs, dirges and military marches along with quadrilles and other classical forms.

In the late 1800s, the city had over 100 brass bands, most of which were affiliated with fraternal orders, fire companies, militia companies, as well as various social and benevolent organizations — “mutual-aid” societies created to fund medical, funeral and burial services for dues-paying members. In his book Mitchell notes that in celebrating Mardi Gras around the turn of the century, “white maskers hired black bands to ride with them in spring wagons, providing music for their dancing.” These horse- or mule-drawn wagons were forerunners of the bandwagons found in today’s Carnival parades.

Not long after Louis Armstrong came into the world and began soaking up the sounds of the Crescent City, jazz animated Carnival parades. Mardi Gras, explains Mitchell, “did not ‘create’ jazz. It did, however, reflect the reasons New Orleans would become the birthplace of jazz….” Or as parade designer and Carnival historian Henri Schindler puts it in his book Mardi Gras: New Orleans (Flammarion, 1997), “the joyous license of the music owes more than a passing acquaintance to the liberties of Mardi Gras and a population long-accustomed to dancing in the streets.”

Louis Armstrong reigning over the 1949 Zulu parade

Armstrong played in the Zulu parade as a young man and can be heard on King Oliver’s “Zulu’s Ball”; released in 1923, it became the first in an evolving canon of recordings that pay homage to the iconic social aid and pleasure club.

— Photo courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum

In his autobiography, Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans (Prentice-Hall, 1954), Armstrong recounts having had the misfortune of stopping for a beer at a barroom that was near the scene of gunshots. Wrongly suspected of being a culprit, he was briefly incarcerated.

Released from prison on Fat Tuesday, Armstrong ran into the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club parade. “It’s a funny thing how life can be such a drag one minute and a solid sender the next,” he writes. “When I ran into this celebration and the good music I forgot all about Sore Dick [the dreaded prison yard captain] and the Parish Prison.” He went on to note that the Zulus “march to the good jumping music of brass bands while the King on his thrown scrapes and bows to the cheering crowds.”

Zulu itself can be seen as a reflection of rollicking, improvisational aesthetic that would come to characterize what we now know as traditional New Orleans jazz. Instead of scripted decorum of the old blue-blood Carnival krewes, the Zulus offered the exuberance and spontaneity of the second line, whereby spectators, musicians, parade marchers and even float raiders would — to borrow a phrase from Armstrong — “pitch a boogie-woogie.”

Second lining grew out of traditional African-American parades — specifically, jazz funerals. Strictly speaking, the “second line” refers to the secondary mass of people — uninvited guests whom everyone expects to show up — who join in the processions, following behind the hearse, mourners and brass band (i.e., the “first line”).

Before arriving at the cemetery, the band plays solemn dirges. But after the services, when the procession is a respectable distance away from the sacred space, the musicians celebrate the life of the deceased by bursting into up-tempo parade bounces. The distance between the performers and the audience breaks down, as the second liners engulf the band, moving to the beat as bodies strut and gyrate, as handkerchiefs wave and fancy umbrellas twirl. It is the role of the grand marshal, whose accouterments may include a staff and a whistle, to regulate the tempo of the procession. (Note, however, that in the context of Mardi Gras parades, the grand marshal is more often than not an honorary role featuring a local or, in the case of the Krewe of Endymion and Krewe of Orpheus, national celebrity.

Sylvester Francis of the Backstreet Cultural Museum, with Mardi Gras Indian suits by Victor Harris of the Mandingo Warriors in the background

The “irresistibly funky” cadence of the second-line beat underlies many of the greatest songs in the Carnival music canon.

More generally, the term denotes a parade involving a brass band, Mardi Gras Indians or second-line club. It’s also the name for a style of dancing inspired by the distinctive syncopated rhythm associated with New Orleans-style processions.

Sylvester Francis, proprietor of the Backstreet Cultural Museum in the Tremé neighborhood, elaborates. “In a general sense,” he relates in a script for one of his exhibits illuminating local culture, “ ‘a second line’ beat refers to the many syncopated rhythms heard in New Orleans jazz and R&B. As a song moves along, there are slight differences in rhythmic emphasis from one measure to the next, creating a loose-yet-tight, push-and-pull feeling that is irresistibly funky. More specifically, a second line beat is also defined as an accent that falls between the fourth and final beat of one measure and the first beat of the following measure — bomp bomp bomp bomp BA-BOMP — that helps to propel a strutting, up-tempo song. Two popular examples are the brass-band standard “It Ain’t My Fault” (written by Smokey Johnson and Wardell Quezergue in 1966) and Joe Avery’s classic “Second Line” recorded in the 1950s.” (Both songs are beloved staples of the Carnival songbook.)

On the most fundamental level, it all goes back to Africa. In the documentary Jazz Parades, the late folklorist Alan Lomax notes the similarities between second-line parades and traditional parades in West Africa, where the band is an integral part of the dancing crowd. “You see it in the crouching, sliding steps; in the improvisation of the dancers. Most prominently in the change of level, from low to high and back again, which is so characteristic of Africa,” he observes.

In colonial times in New Orleans, the focal point of Afro-Caribbean musical and dancing culture was the Place des Negres, later renamed Congo Square, where slaves were allowed to gather on Sundays. Until it was suppressed around 1835, Congo Square was a public market and venue for communal drum-and-dance convocations, providing continuity for African forms of festive merriment that nurtured the creation of second-line parades and jazz. The percussive rhythms and call-and-response chants that drove the revelry entered the vernacular of New Orleans music, yielding a primal undercurrent that would later become the foundation of funk.

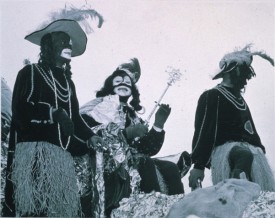

The key conduits of the Congo Square drum-and-dance tradition are Mardi Gras Indians — African-Americans and mixed-race celebrants who “mask Indian.” Slaves and Native Americans intermingled from the earliest days of colonial Louisiana. They shared similar belief systems involving ceremonial communion with ancestral spirits. And both groups had in common the experience of being subjugated by the dominant culture. As racial repression intensified in the post-Reconstruction era, hardening the color line governing participation in the Carnival, organized groups of Mardi Gras Indians, as they came to be known, took to the streets on Fat Tuesday. By masking Indian, they expressed ritual freedom, provided continuity to Afrocentric forms of festive performance and paid homage to tribes that provided refuge to runaway slaves.

Offering temporary escape from rigidly defined roles and boundaries, Carnival allowed New Orleanians of African descent to symbolically reclaim the festive space of Congo Square. “The Indians would never have entered the folk streams of New Orleans music had it not been for Carnival,” conclude co-authors Jason Berry, Jonathan Foose and Tad Jones in Up From the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music Since World War II (Da Capo Press, 1986).

The Guardians of the Flame Cultural Arts Collective, accompanied by percussionist Bill Summers (far left), on Mardi Gras 2009

Combining music, dance and elaborate costuming, the Mardi Gras Indian tradition is a conduit for cultural retention, bringing communities together to interpret their past, express ritual freedom and honor their ancestors.

The music of Mardi Gras Indian tribes, or “gangs,” can be characterized as “call and response,” with the lead singer backed by a chorus and percussion. Generally speaking, their songs celebrate acts of bravery and defiance (“We won’t bow down”), as well as the proud heritage of the Indian nations. Lyrics include coded chants such as “tu way pocky way,” “oom bah way,” “mighty kootie-fiyo” and “Coochee marlee.”

Financed in part with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Maruice Martinez, a New Orleans Creole, produced the first documentary on Mardi Gras Indians,The Black Indians of New Orleans, in 1975. Now a professor of education at the University of North Carolina, he has delved into the origins and mysteries of Mardi Gras Indian vernacular, which is derived in part from Creole patois.

At a presentation on Mardi Gras Indians at the 2010 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, he explained the etymology of

the exhortation “Coochee marlee!” Turns out the expression, often associated with the Mardi Gras Indian position of spy boy or scout, pertains to the legendary Seminole chief Coacoochee, aka Wild Cat, whose many exploits included helping slaves escape bondage. Creoles having a tendency to eliminate syllables, his name was shortened to Coochee. “So when Coochee came along, he say, ‘Follow me to freedom; get out of this wretched existence you’re in, in this racist South,’ ” explained Martinez. “And of course, in Creole, you don’t say Je vais — ‘I go’ — you say, ‘Me go.’ So it’s Moi aller, not Je vais. When you say it fast enough, it’s ‘marlee.’ ” So when African Americans would yell “Coochie marlee!” it referenced the path to freedom, related Martinez: “ ‘Coochee’s comin’, man. You want to go? Let’s go!’ ”

Nowadays when a spy boy hollers “Coochie marlee!” it roughly translates as “Here I am, let’s go!” (The reason the expression became associated with the spy boy is that some of the Black Seminoles in Coacoochee’s band became scouts for the U.S. Cavalry).

In a city where culture bubbles up from the streets, the lyrics and beats of the Mardi Gras Indians have inspired and informed an extraordinarily diverse range of players, from jazz legends (Jelly Roll Morton and Danny Barker) to masters of New Orleans funk (The Meters and The Neville Brothers), rhythm and blues (Professor Longhair, Earl King and James “Sugar Boy” Crawford) and even modern jazz (Donald Harrison Jr.).

In his memoir Under a Hoodoo Moon: The Life of Dr. John The Night Tripper (St. Martin’s Press, 1994), Rebennack recalls growing up hearing Mardi Gras Indians play “a real funky kind of street music.” For his Goin’ Back to New Orleans album, released on the Warner Bros. label in 1992, The Night Tripper assembled a team of local musical luminaries, among them Howard “Smiley” Ricks, a percussionist and Mardi Gras Indian. One of the album’s standout tracks is a thumping rendition of a traditional Mardi Gras Indian song, “My Indian Red,” arranged by Barker. On the cover of the album, which pays tribute to the polyglot musical heritage of the Crescent City, Dr. John appears in full Mardi Gras Indian regalia: an elaborate hand-sewn suit of plumage and beadwork.

Dr. John’s Grammy-winning Goin’ Back to New Orleans album

A superlative evocation of the Crescent City’s polyglot musical heritage.

The Mardi Gras Indian tradition goes back at least as far as Reconstruction, though it wasn’t until the 1950s that the sounds associated with that tradition began to be translated into popular music. Sugar Boy Crawford’s “Jockomo,” released on the Chess label in 1954, became a jukebox classic. And Huey “Piano” Smith used the Indian chant “Oom bah way, tu way pocky way,” in the very first line of his hit “Don’t You Know, Yockomo.”

The most enduringly popular song associated with the black Indians of New Orleans is “Big Chief.” Written by the late New Orleans guitarist-composer Earl King, also the originator of the Mardi Gras anthem “Street Parade,” the song was first recorded in 1964 for Watch Records. The session included Rebennack, who later became known as Dr. John, on guitar and Professor Longhair on piano. King whistles and handles the vocals on “Big Chief Part 2″ (“Me big chief me got ’em tribe/got my spy boy by my side”), considered to be the session’s definitive version.

King, who wrote the song for Professor Longhair, describes its origins in the radio documentary Come on Baby Let the Good Times Roll: The Story and Music of Earl King, produced by David Kunian. “It was really about an Indian breaking into the commissary and stealing the whiskey out of there in one of those little towns,” he relates. The song’s title, however, was inspired by King’s mother. A cousin had nicknamed her “Big Chief,” he explains in the documentary, because she was a heavy woman who would “go on the warpath” when chores were neglected.

“Big Chief” became a signature song for Professor Longhair and can he heard on Crawfish Fiesta (Alligator), Big Chief (Rhino) and House Party New Orleans Style (Rounder), among other albums.

Growing up in New Orleans, the Professor became uniquely attuned to the rhythms of the streets. He danced tap on Bourbon Street and frequently joined in second-line parades, beating out rhythms on bottles, cans or whatever objects were at hand. He later accentuated the swinging marching-band music of street parades in his distinctively percussive piano playing. As George Winston has noted, the “Fess” had three basic styles: rhumba boogie, slow blues and straight calypso.

“Go to the Mardi Gras,” probably his most famous composition, is a rhumba boogie that conveys the aural effect of a train ride. The narrator of the song is rolling into New Orleans for Mardi Gras — specifically, the parade of the Zulus. Fess first cut the song in 1949 for the Dallas-based Star Talent label, but that version was never released. Another version was cut in 1950 by Atlantic Records. But the 1959 Ron Records version is the keeper. “Propelled by John Boudreaux’s feverish second-line drumming, and a scrappy New Orleans horn section, the song’s festive lyrics and Longhair’s melodic whistling make this the unforgettable treatment,” writes Jeff Hannusch in the liner notes for Collector’s Choice, a Rounder release.

Dr. John, who played guitar on the Ron session, has credited Fess with having “put funk into music,” and indeed “Go to the Mardi Gras” exemplifies the Afro-Caribbean sensibility that has shaped the cultural identity of New Orleans since the days of Congo Square.

Professor Longhair, aided by the likes of conga player Alfred “Uganda” Roberts, channeled the primal beat of Congo Square. But it wasn’t until the release of commercial recordings of Mardi Gras Indians that a concentrated form of this New Orleans roots music was widely heard outside the mostly black, working-class neighborhoods were the Indians performed.

New Orleans keyboardist and pop R&B composer Willie Tee, aka Wilson Turbinton, and his brother, saxophonist Earl Turbinton Jr., had grown up in the midst of Mardi Gras Indians in New Orleans’ Calliope housing project. The Willie Tee band first played with the Wild Magnolias Mardi Gras Indians at the Tulane Jazz Festival in 1970. Several years later Tee assembled a stellar group of local musicians, called The New Orleans Project, for a session with The Wild Magnolias, led by Theodore Emile “Bo” Dollis, and Joseph Pierre “Monk” Boudreaux, chief of The Golden Eagles tribe and boyhood friend of Dollis’s.

The Wild Magnolias, released on the Polydor label in 1974, combined the chants and funky percussion rhythms of the Indians with jazz-flavored jamming. The follow-up, They Call Us Wild, was released in 1975.

“The blend of Chief Bo Dollis’ fierce vocals, Willie Tee’s slinky keys, Earl Turbinton’s screaming sax, percolating conga (from Prof. Longhair collaborator Alfred ‘Uganda’ Roberts) and wah-wah space guitar (from the original of a long line of ‘Guitar June’s, ‘Guitar June’ Johnson Jr.) results in an absolutely flawless long-form funk,” writes Roger Hahn in Offbeat, adding that “the mostly original song list is steeped in terrific tunes based on subjects derived from black Indian culture (‘New Suit,’ ‘Fire Water,’ ‘Injuns, Here We Come,’ ‘New Kind of Groove,’ ‘We’re Gonna Party’). It may have been a short-lived experiment, but on They Call Us Wild, the blending of black Indian culture and the emerging genre of funk reaches a rarified pinnacle of popular musical expression.”

They Call Us Wild, originally a Europe-only release, remained something of an underground legend until being re-released on PolyGram in 1994. A long-awaited new album, Life is a Carnival, reuniting Bo Dollis and The Wild Magnolias with Monk Boudreaux, appeared on the Metro Blue label in spring 1999. It Included are four new songs by special guest Dr. John, as well as a rendition of his anthem “Mardi Gras Day.” Robbie Robertson is featured on the title tune, taken from the songbook of his old group, The Band. Other guests include Bruce Hornsby, Cyril Neville, Marva Wright and Davell Crawford.

“The Wild Magnolias” broke new ground by fusing Mardi Gras Indian music with more popular idioms. But the most influential Mardi Gras Indian recording of all time is The Wild Tchoupitoulas, released in 1976 by Island Records. It marked the first time that The Neville Brothers — Art, Charles, Cyril and Aaron — came together as an ensemble.

They united behind their uncle, the late George Landry, who was the driving force behind the project. Better known as Big Chief Jolly, he led The Wild Tchoupitoulas, an Uptown tribe. A former merchant seaman, Uncle Jolly played blues piano, banged out rhythms on the tambourine and spun lyrics from Mardi Gras Indian street lore.

The Wild Tchoupitoulas is described in Up From the Cradle of Jazz as “one of the great musical statements issued from New Orleans, a remarkable fusion of street chants and folk rhythms set to brilliant instrumental and percussive backing.”

Laying down the slippery grooves: The Meters, the seminal funk outfit founded by keyboardist-composer Art “Poppa Funk” Neville. Back in 1954, at the tender age of 17, Neville, as leader of The Hawketts, achieved jukebox immortality when he did the vocals on “Mardi Gras Mambo,” one of the most popular Mardi Gras tunes of all time. The song was recorded again in 1975 by The Meters on their Fire on the Bayou album. A year after the release of The Wild Tchoupitoulas, The Meters disbanded and Art joined forces with his brothers.

Chief Jolly died in 1980, but his spirit lives on in the funky rhythms and soulful vocal harmonies of The Neville Brothers. In their live performances, especially during Carnival, the Nevilles like to tip their hats to Uncle Jolly and the Indians by playing songs such as “Brother John,” “Iko Iko” and “New Suit.”

Chief Jolly figures prominently in two cuts on the Nevilles’ Grammy-winning 1989 release on A&M Records, Yellow Moon. “Wild Injuns,” an original song, is a rambunctious tribute to “Mardi Gras Injuns down in New Orleans.” And in a reworking of A.P. Carter’s gospel classic “Will the Circle be Unbroken,” Cyril Neville mourns the passing of his beloved uncle: Undertaker, undertaker/ won’t you please drive real slow/That’s Chief Jolly that you carry/I sure hate to see him go.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Charter School band in the New Orleans Saints Super Bowl victory parade, aka Lombardi Gras

For New Orleanians, the parade-time beats of high school marching bands are inextricably associated with the excitement of Carnival.

Over the years, the brass band tradition has proven no less of a wellspring of Mardi Gras music than the Mardi Gras Indian tradition. Many of the city’s top horn players started out playing in Mardi Gras parades. No matter how spectacular the floats, a parade isn’t a parade without the rhythmic excitement of the bands.

“When I used to go to Mardi Gras parades,” Stanton Moore recalled in Offbeat, “the first thing you’d hear coming down the street was the drums. I would get so excited. I think that funk music just gives you that same feel, that rhythmic feel that makes you go, ‘Oh, yeah, here it comes!’ ” (Moore is the drummer for New Orleans funk band Galactic.)

As the authors of Up from the Cradle of Jazz point out, “New Orleans music is built from the bottom up: drums first, bass second, then guitar and horns.”

“In New Orleans roots music,” Dr. John relates in his memoir, “the drummer is crucial, chronic to our thing because he lays down the foundation of what New Orleans music is all about: the funk.” The New Orleans drummer, he adds, “leans heavily on the bass drum, playing double-clutch rhythms” and breaking up the beat into “two-and-four-bar patterns (and sometimes even an eight-bar pattern).”

As Dr. John recounts in liner notes, New Orleans session drummer nonpareil Earl Palmer had a name for this New Orleans style of syncopation: ” ‘Let’s play a little Funky Butt,’ he’d say. That’s exactly what it was. Music to make you dance and shake your butt until your butt is funky.”

Historian Mitchell notes in his book that trombonist Kid Ory, a major force in jazz in the first half of the century, “won the second-liners over with his version of ‘Funky Butt,’ a ‘ratty’ song.” (In the early 1900s, Ory once played at a notorious venue in the uptown red-light district, i.e., Black Storyville, popularly known as Funky Butt Hall; it was also the first place Louis Armstrong heard the music later called jazz.)

Culture bearer extraordinaire Danny Barker

The Mardi Gras music tradition has benefited greatly from the brass band revival he set in motion.

— Photo by Pat Jolly

Mardi Gras music has received a tremendous boost from the brass band revival movement that has been going on in New Orleans since the early 1970s. It all began after the late Danny Barker — a banjo and guitar player who worked with everyone from Jelly Roll Morton and Bunk Johnson to Cab Calloway, Benny Carter and Lucky Millinder — returned to his native New Orleans from New York and started the Fairview Baptist Church Band to turn young people onto the classic brass band tradition. Out of that came The Dirty Dozen Brass Band. A key force in reviving the street-parade tradition, the Dozen mingled an improvisational style of traditional jazz with bebop, funk and R&B — and thus inspired a new generation to pick up horns and evolve the music in new directions.

Most of the members of the ReBirth Brass Band were in high school when the band started out in the mid-1980s. They got their break in 1990, after the release of their first album on Rounder the year before. The title song, “Do Whatcha Wanna,” became a big smash with the young late-night crowd after club DJs started spinning it between hip-hop and rap numbers. The song, with a throbbing tuba bass line and a chorus shouted like a Mardi Gras Indian chant (“Do Wat-cha Wanna….Do Wat-cha Waaa-na!”), got picked up by black commercial radio and became a local hit, something no brass band had ever achieved. Blasting from car stereos, jukeboxes and front porches all over the city, it became the party theme song for the 1991 Carnival season.

Just about every Carnival season since has brought new would-be anthems, though none has hit as big as “Do Watcha Wanna.” “Indian Princess,” written by J. Monque’D, was released in early 1994 and quickly became the single for that year’s festivities. Against rolling rhythms reminiscent of “Go to the Mardi Gras,” the late R&B diva Marva Wright, trading vocal leads with Monque’D, sings of a princess turned queen (“I’m a big queen ju-kin’ and jum-pin’ “). The chorus features the Creole Wild West Mardi Gras Indians. Two years later, “Gimme My Money Back,” by The Treme Brass Band, emerged as a Mardi Gras anthem.

Mardi Gras songs usually reflect the musical sensibility of the era in which they’re written. The rhythms of modern urban culture inform Young Guardians of the Flames’s 1998 release, New Way Pockey Way (First Tribe Records). The title track is a traditional Mardi Gras Indian song infused with funk and elements of hip hop.

Members of the Harrison family figure prominently in the Young Guardians, which is an extension of The Guardians of the Flame. Donald Harrison Sr., the late big chief of the Guardians tribe, contributed vocals and lyrics on New Way Pockey Way. Son Donald Harrison Jr., one of the premiere jazz saxophonists of his generation, arranged four of the songs.

Jazz drummer Idris Muhammad (left) and saxophonist Donald Harrison Jr., masking as the Congo Nation on Carnival Day 2003

The once-obscure music and traditions of Mardi Gras Indians, synthesizing African, Caribbean and American folkways, are now emblazoned on the aesthetic and cultural consciousness of New Orleans and beyond.

Donald Jr. is responsible for the groundbreaking album Indian Blues, released in 1989 on the Candid label. Featuring Dr. John, Smiley Ricks and The Guardians of the Flame, it synthesizes Mardi Gras Indian music and modern jazz.

In an interview with Offbeat, Harrison recalled how the idea for the album came to him when he was masking Indian with his father’s tribe. “I had this magical revelation one Mardi Gras,” he relates. “I was hearing how the Indian music and jazz could be merged together. I was hearing the swing beat in the Indian music.”

It’s no wonder that musicians are drawn to Mardi Gras and its fabled cornucopia of sensory stimuli. In a way, the exuberant kaleidoscope of Mardi Gras is a metaphor for the cross-pollination and collaboration that characterizes the local music scene.

In liner notes for Ain’t No Funk Like N.O. Funk, a compilation of contemporary New Orleans funk, Davis Rogan recalled his experience marching with Krewe of Jew-Lu on Mardi Gras 1998. (Jew-Lu is a Carnival club founded in 1993 by the New Orleans Klezmer Allstars.)

“Everyone in purple afro wigs, weird glasses, silk and sequined costumes, drinking their beer and wine….In addition to members of the Klezmers, Mas Mamones, the Iguanas, Royal Finger bowl (and it turns out non-New Orleans artists including Leftover Salmon, G-Love’s Special Sauce and Blues Traveler), there were members of Galactic, Walter Wolfman Washington’s Roadmasters, All That, Iris May Tango, Flavor Kings, Smilin’ Myron, Brides of Jesus, New World Funk Ensemble and The Nightcrawlers.

“It’s that kind of tight music scene down here…,” adds Davis, who plays keyboards for All That. “The birthplace of jazz, New Orleans is the greatest musical Mecca on the planet.”

MardiGrasTraditions.com